Follow us on Google News (click on ☆)

Thanks to multi-isotopic analyses carried out on human remains, the researchers reveal that these individuals belonged to groups from outside the territory, suggesting that these conflicts were part of the reassertion of local power.

Deposits of human remains linked to a context of violence dating from the end of the Middle Neolithic in the Alsace region:

A) pit 157 of Bergheim “Saulager”

B) pit 124 of Achenheim “Strasse 2, RD 45”

© Philippe Lefranc / INRAP.

The Neolithic sites of Achenheim and Bergheim, in Alsace (4300-4150 years before our era), constitute one of the oldest and best-documented examples of conflicts in European prehistory. Previous research on these sites had revealed that the individuals found in circular pits, particularly those represented by complete skeletons, bore multiple signs of "excessive and unnecessary" violence, suggesting a massacre. These pits also contained isolated bone segments from severed left upper limbs.

However, this unique context does not correspond to the typical massacres or executions known in the archaeo-anthropological record of the European Neolithic.

Based on multi-isotopic analyses carried out on bones and teeth, an international team including researchers from the Laboratoire méditerranéen de préhistoire Europe-Afrique (LAMPEA - CNRS/Univ Aix-Marseille/Inrap) reconstructed the diet and documented the social and geographical origin of the studied human remains. The new biogeochemical data were compared with a reference dataset made on other individuals from the region buried in so-called conventional graves and identified as "non-victims".

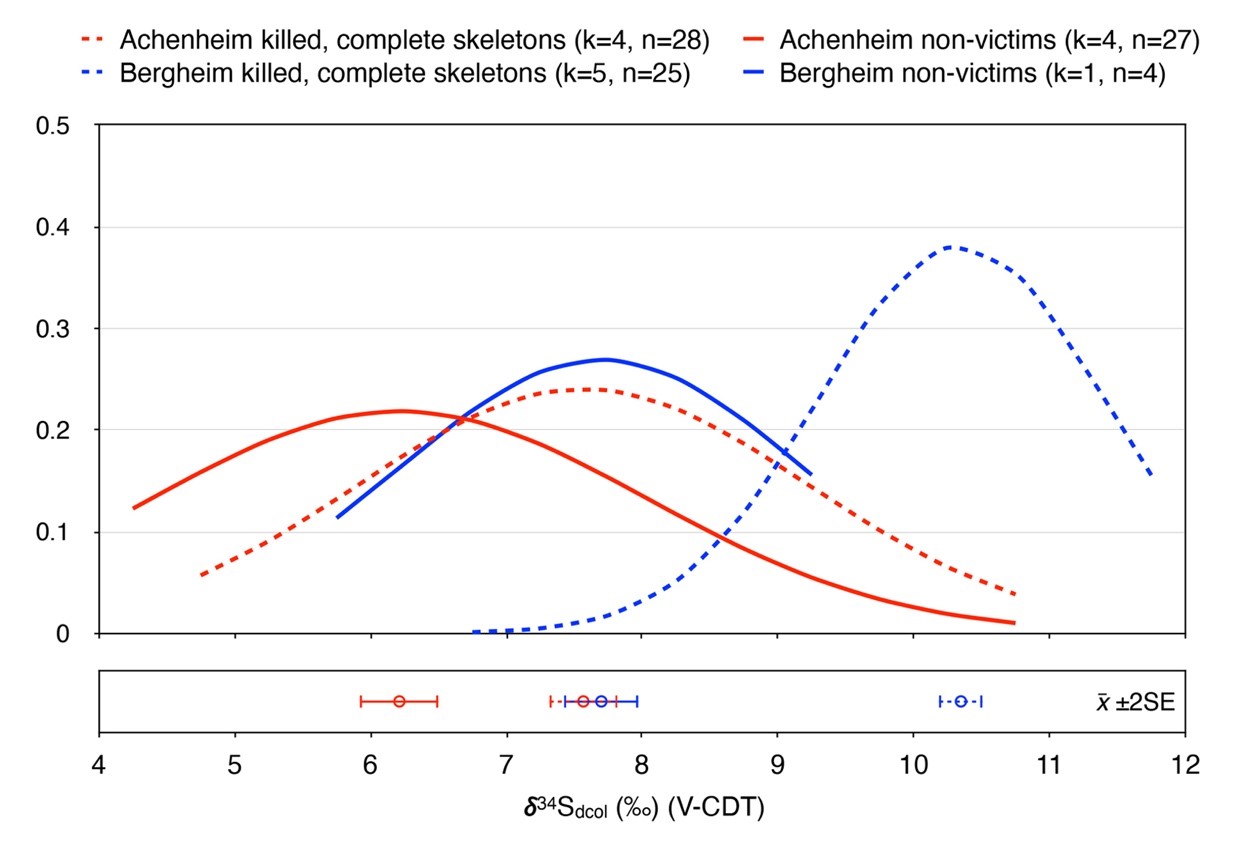

The results reveal significant isotopic differences between the massacred subjects and the "non-victims". The profiles of the former indicate greater mobility, a more varied diet, and potentially higher physiological stress, revealing a substantially different lifestyle.

Distribution densities of sulfur isotope compositions in dentin collagen (δ34Sdcol) from the Bergheim "Saulager" and Achenheim "Strasse 2, RD 45" sites, according to burial context (victims vs non-victims)

© T. Fernández-Crespo.

This data confirms the hypothesis that they were allochthonous individuals, meaning they originated from another territory. Furthermore, sulfur isotope compositions highlight significant distinctions: the complete skeletons could originate from southern Alsace, while the severed limbs would come from individuals from the north of this region.

This study suggests that these events were not merely acts of violence, but had a broader dimension, reflecting the reassertion of a form of power over a local territory. It thus provides a new perspective on the identification of victims of interpersonal violence and underscores the interest of combining different methods of analysis.