Follow us on Google News (click on ☆)

A recent publication in the journal PLOS One provides an analysis of this site named Carreras Pampa. Researchers documented an unparalleled density of footprints there, setting several world records. Their work is not limited to a simple inventory. It reveals the behaviors of these animals, from walking to swimming, captured in the mud turned to stone. This study positions Bolivia as a major hub for ichnology, the science that studies fossil traces.

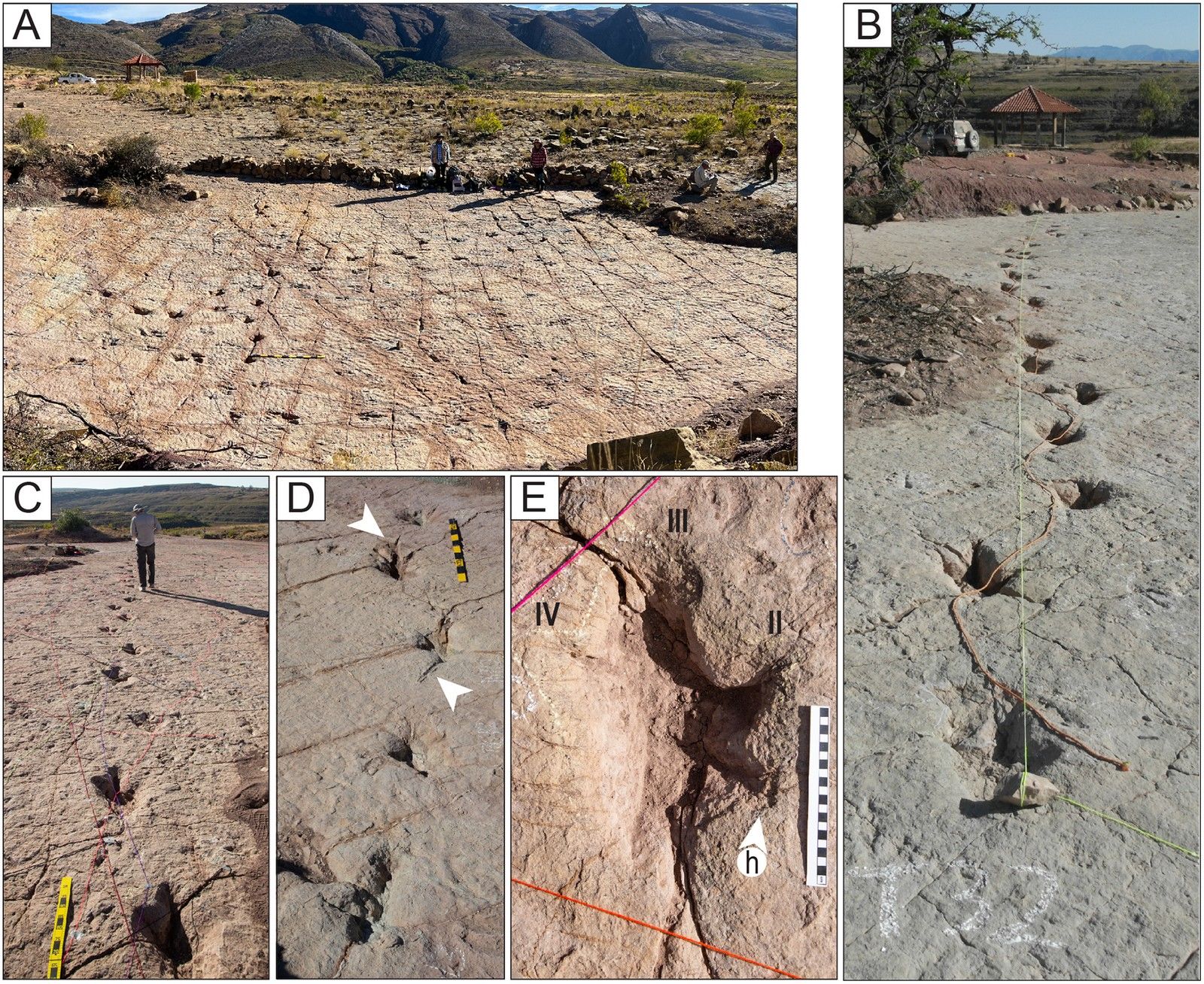

A) M5-type footprints at site CP3. Note the ripples on the surface of the layer.

B) Footprint T32 shows very deep traces and grooves. The sinuous cord marks the grooves.

C) Deep footprints T22-2-25.

D) Set of five very deep footprints TS102. The white arrowheads indicate the grooves.

E) Footprint T22-126. The digits are marked by the numbers II, III, and IV. h = hallux. The scales in C and D are 10 cm (approx. 4 inches), and the scale in E is 20 cm (approx. 8 inches)

A Cretaceous Fossil Highway

The meticulous examination allowed cataloging over 16,000 theropod footprints, bipedal dinosaurs that were mostly carnivorous. These marks are distributed across 9 distinct sectors and show a wide range of sizes, from traces less than 10 centimeters (approx. 4 inches) to footprints exceeding 30 centimeters (approx. 12 inches) in length. This diversity testifies to the passage of individuals of all ages and perhaps many different species on this same coastline.

The spatial organization of the tracks is particularly telling. Most of them follow a northwest/southeast orientation, parallel to the fossilized current ripples in the rock. This configuration indicates that the animals moved mainly along the shoreline. However, movements were bidirectional, which rules out the hypothesis of a single seasonal migration. Scientists suggest regular back-and-forth movements, indicating a heavily frequented travel route.

The quality of preservation is remarkable. Beyond simple footprints, paleontologists have identified sequences showing turns, accelerations, and stops. Some straight tracks extend over long distances, while others reveal marks from slides or tail drags. This richness allows for the reconstruction of movement dynamics with a level of detail rare for such a remote period.

Swimming, a Documented Behavior

One of the most striking aspects of this study concerns the discovery of more than 1,300 footprints interpreted as swimming traces. These marks, formed when the animals propelled themselves over a muddy bottom in shallow water, are sometimes isolated or form short trackways. Their analysis provides a glimpse of how these theropods interacted with the aquatic environment, a behavior difficult to grasp by other means.

Researchers observe variable swimming modes. Some sequences show regular spacing between footprints, indicating the animal was taking rhythmic toe pushes against the substrate. Other traces, more sporadic, seem to correspond to occasional touches, perhaps in slightly deeper water or during a more extensive movement. This difference could also be explained by the size of the animals, with larger ones touching the bottom more frequently.

These aquatic traces do not imply these dinosaurs were specialized swimmers. They seem to have ventured into the water opportunistically, for a reason that remains unknown. This extensive documentation is valuable, as direct evidence of swimming in dinosaurs is rare. It shows that this behavior, previously associated with a few species like spinosaurs, may have been more widespread among theropods in specific coastal environments.