🔭 Giant quasars: discovery of dozens of intergalactic structures

Published by Adrien,

Source: The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series

Other Languages: FR, DE, ES, PT

Source: The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series

Other Languages: FR, DE, ES, PT

Follow us on Google News (click on ☆)

This discovery is part of a larger set of 369 radio quasars spotted in the data from the TIFR GMRT Sky Survey (TGSS), which scanned nearly 90% of the sky visible from Earth. The sensitivity and wide coverage of the GMRT were crucial for detecting these gigantic and often very distant structures.

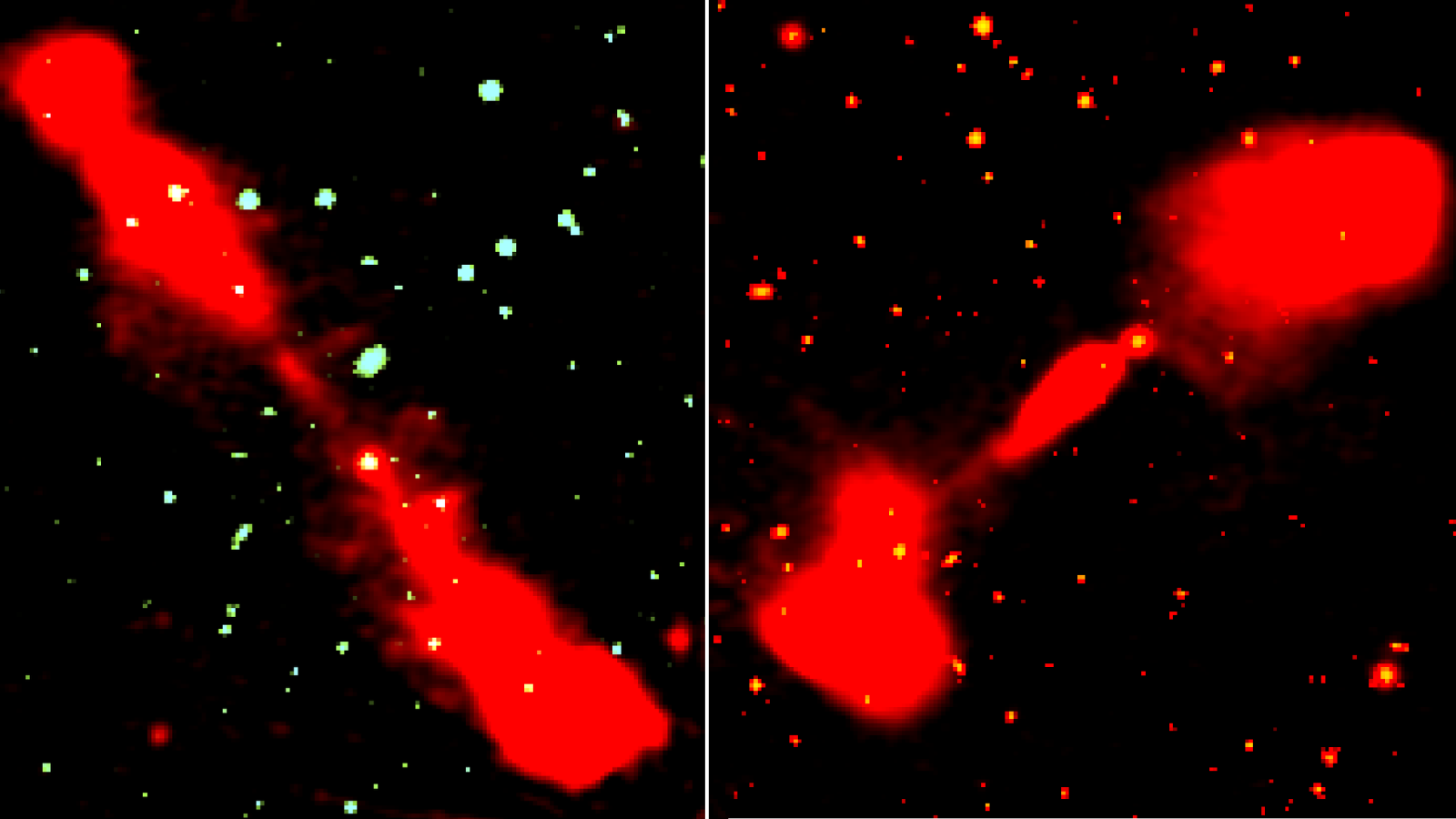

Two examples of giant radio quasars recently discovered, each spanning millions of light-years.

Credit: Pal, et al (2025)

These quasars are powered by supermassive black holes, whose mass equals millions or billions of times that of the Sun. Located at the centers of galaxies, these black holes attract enormous amounts of gas and dust that form an accretion disk around them.

Friction within this disk heats the matter, producing intense radiation. However, some of this material is not absorbed; it is channeled by magnetic fields towards the black hole's poles, then ejected at extreme speeds in the form of twin jets. As these jets move away, they widen to form vast lobes emitting mainly in the radio domain.

The researchers observed that these giant jets often show a marked asymmetry in length or brightness. This asymmetry reflects the unequal conditions of the intergalactic medium they traverse. One side of the jet may encounter denser gas clouds, which slows its expansion, while the other propagates freely in a more tenuous environment. This interaction with the surrounding medium shapes the evolution of the jets and offers valuable clues about the composition and density of the gas between galaxies (see the explanation on jets as probes at the end of the article).

The study also reveals that at least 14% of these giant quasars reside within galaxy clusters or filaments, where matter is more concentrated. In these dense regions, the jets can be slowed, deflected, or fragmented by the ambient gas. Conversely, in emptier areas, they can extend unimpeded over greater distances. This environmental influence helps understand why some quasars develop such colossal structures.

The most distant quasars, thus observed at a more remote epoch of the Universe, generally show more pronounced asymmetry. This could be explained by a younger cosmos, more turbulent and rich in gas, which disturbed the jets' trajectory more. By analyzing these objects, astronomers reconstruct not only the history of supermassive black holes but also that of the Universe itself, from its initial phases to its current state.

Detecting these structures poses technical challenges, as the radio link between the two lobes can become too weak to be perceived, giving the impression of an incomplete structure. Low-frequency surveys, like the one conducted with the GMRT, are particularly suitable because older lobes emit more strongly at these wavelengths. This approach has unveiled a hidden population of giant quasars, opening new perspectives for mapping large cosmic structures.

Radio jets, probes for the distant Universe

The matter jets emitted by giant radio quasars serve as true natural probes for studying otherwise inaccessible regions of the Universe. While traversing the intergalactic medium, they reveal its density, composition, and structure on scales of several million light-years. Their behavior thus informs us about the environment in which galaxies evolve.

When a jet encounters a denser gas cloud, its progression is slowed, and its radio emission can be affected. This explains why jets often show an asymmetry: one side may appear shorter or less bright because it encountered more resistance. By analyzing these differences, astronomers can indirectly map the distribution of diffuse matter between galaxies.

Furthermore, since light takes time to reach us, observing a distant quasar amounts to looking into the past. The most distant quasars show us the Universe at a time when it was younger, hotter, and denser. The strong asymmetries observed in some of them indicate that the intergalactic medium was more turbulent then, with more pronounced density contrasts.

Finally, studying these jets helps understand the life cycle of supermassive black holes and their influence on galactic evolution. The energy released by these jets can heat or disperse the surrounding gas, thereby regulating star formation in the host galaxy or its neighbors. These feedback processes are fundamental in the formation of the large structures we observe today.