Follow us on Google News (click on ☆)

The research shows that exploiting these mechanisms allows for a qualitative immune response in mice following vaccine application through skin massage. These results, to be published in Cell Reports, provide new insights into the role of mechanical stimuli in skin immune responses and open the way to new alternatives to drug injections.

What if administering a vaccine became as common as applying cream?

Illustration image Pixabay

The skin constitutes the body's protective barrier against environmental aggressions: UV rays, toxic molecules... It must constantly adapt to effectively perform its role.

It is also permanently subjected to intrinsic mechanical tensions specific to its complex structure[1]. During skin injury or inflammation, this "mechanical stress" plays a major immune role, particularly by finely modulating the action of certain immune cells sensitive to tension variations in the skin.

However, regarding external mechanical constraints, the physiological impact of mechanical stress caused by transient skin stretching - such as during friction or massages - remains poorly understood.

A team of researchers coordinated by Élodie Segura, Inserm research director, at the Immunity and Cancer laboratory (Inserm/Institut Curie) and by Stuart A. Jones, professor and director of the Centre for Pharmaceutical Medicine Research, at the Institute of Pharmaceutical Science (King's College London) studied how mechanical stress caused by massage could affect skin immunity and protective impermeability.

The scientists used a tool to stretch the skin to mimic, for 20 minutes without causing injury, a massage applying tension to the skin similar to therapeutic massage or cream application. They then compared several mechanical, microbiological, and physiological parameters of the skin with and without massage in mice and, partially, in human volunteers.

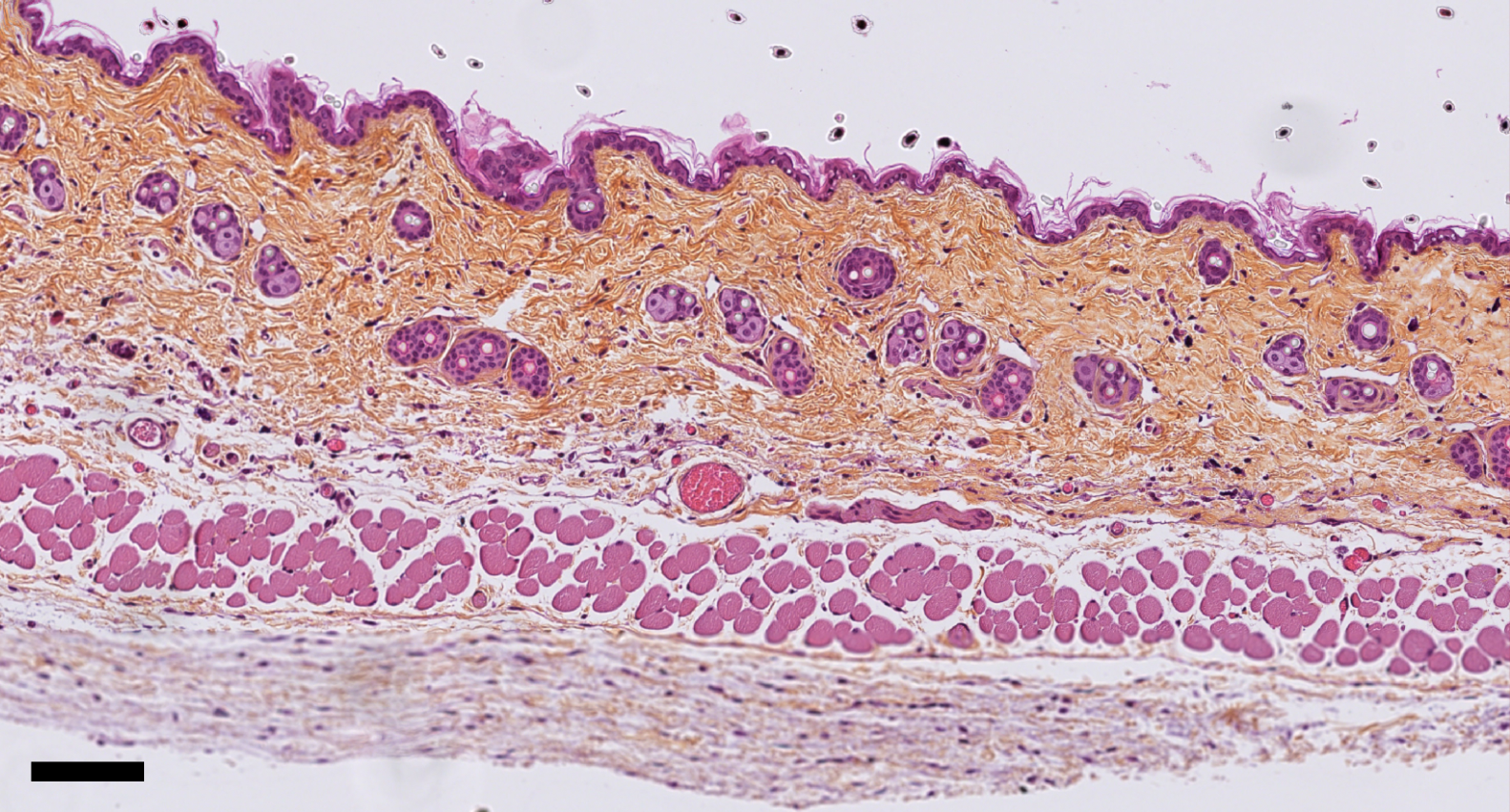

Structure of mouse skin after stretching, by histological staining. The scale bar corresponds to 100 micrometers.

© Darawan Tabtim-On and Renaud Leclère - Experimental Pathology Platform of Institut Curie

They first observed that massage made the skin temporarily permeable to very large molecules (or macromolecules) in both humans and animals. This permeability appeared linked to an opening of hair follicles (the cavity where hair originates), which, facilitated by massage, allowed surface macromolecules to penetrate the skin tissue.

In rodents, the researchers also observed that this opening of hair follicles allowed compounds derived from bacteria naturally present on the skin surface (the skin microbiota) to enter the skin. This phenomenon then triggered an immune response leading particularly to local inflammatory reaction and initiation of the so-called "adaptive" immune response. This immunity, which allows highly specific elimination of pathogens, is the basis of immune system memory and is stimulated by vaccination.

"These results suggest that mechanical stress acts as a danger signal within the skin," indicates Élodie Segura. "The entry into the skin of microbiota compounds facilitated by stretching could thus alert the local immune system to the loss of impermeability of the skin barrier and activate it to respond to potential danger."

Building on these observations, the team investigated the possibility of exploiting these properties to develop a non-invasive vaccination technique through skin application. They applied an influenza vaccine (H1N1) by massage to mouse skin and compared the immune reaction to that produced by conventional intramuscular injection of this vaccine.

"Tests in humans must be conducted to confirm these results observed in mice, as there are well-known differences between the skin of our two species," specifies Élodie Segura. "We will also need to understand how each type of skin cell specifically reacts to mechanical stress and which microbiota products precisely stimulate the inflammatory response. Mastering these processes in humans could thus enable the development of needle-free and non-invasive vaccination or drug administration methods"," concludes the researcher.

But these results could also have important implications from a toxicological perspective. They indeed suggest that skin friction or massage could promote the penetration into the body of harmful molecules - pollutants or allergens present on the skin or in topical creams - and stimulate unwanted immune responses (inflammatory or allergic). However, to date, chemical risk assessments of products do not include the possibility that a macromolecule could enter the skin. Additional studies could therefore investigate the links between mechanical stress and allergen sensitization.

Note:

[1] The skin has a complex multilayer structure, stratified into three main layers: the epidermis (the outermost), the dermis, and the hypodermis (the innermost). Each of these three layers is composed of different cell types and has variable thickness depending on body parts and from one individual to another.