Follow us on Google News (click on ☆)

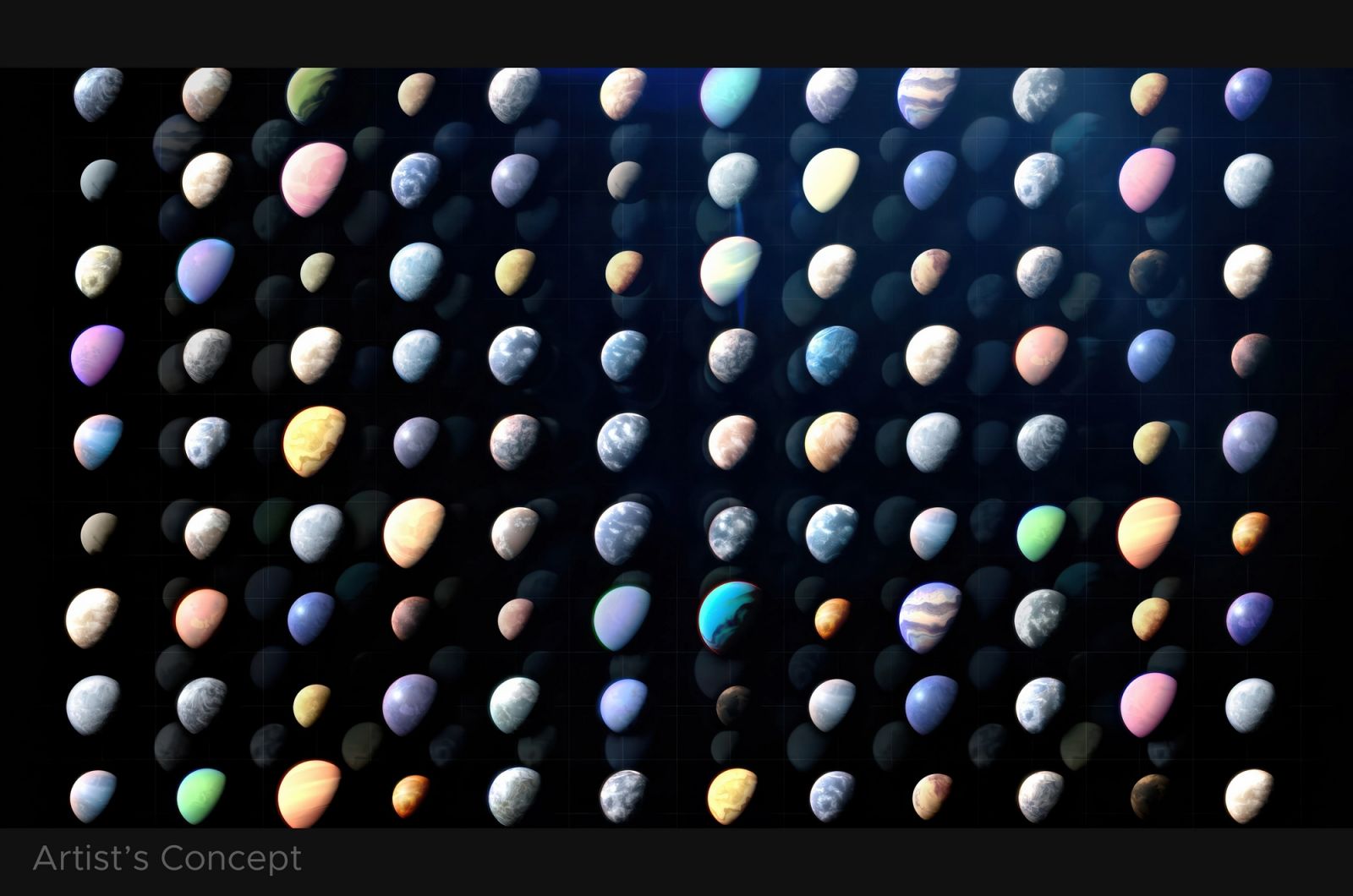

A constantly expanding census

Since the discovery of the first exoplanet in 1995, the hunt for extrasolar worlds has accelerated at a remarkable pace. In 2013, only 1000 objects had been validated. Less than a decade later, in 2022, the 5000 mark was surpassed.

The year 2025 marks a new milestone with 6007 planets officially confirmed as of September 17. The figure is not insignificant, as more than 8000 other candidates are still awaiting examination.

NASA divides these exoplanets into broad categories: 2035 are Neptune-like worlds, 1984 are gas giants similar to Jupiter or Saturn, 1761 are super-Earths, 220 are terrestrial planets (rocky planets close to Earth's size), and 7 are still of an undetermined type.

How to detect these distant worlds?

Exoplanets almost always escape direct imaging. Only 1.4% of cases involve visual observation. The others are spotted using indirect methods.

The most commonly used is the transit method, which measures the decrease in a star's brightness when a planet passes in front of it. It allows for an estimation of the celestial body's size.

The radial velocity technique often complements these observations. It detects the tiny oscillations of a star caused by the gravitational pull of its planet, providing access to the object's mass.

In search of an Earth twin

The term "terrestrial type" currently applies to 220 exoplanets. It refers to rocky worlds of dimensions comparable to our planet, but without direct resemblance in terms of atmosphere or habitability.

The discoveries mainly reveal an unexpected diversity: lava planets, hot Jupiters in tight orbits, or even double-star systems reminiscent of the planet Tatooine from the Star Wars saga.

NASA emphasizes that its primary goal remains the identification of rocky planets capable of harboring life. The study of their atmospheres, with new instruments, could provide clues of biosignatures.