Follow us on Google News (click on ☆)

This discovery, published in Astronomy & Astrophysics, was made possible thanks to data from the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST). It provides new insights into the formation and early evolution of galaxies in the primordial Universe.

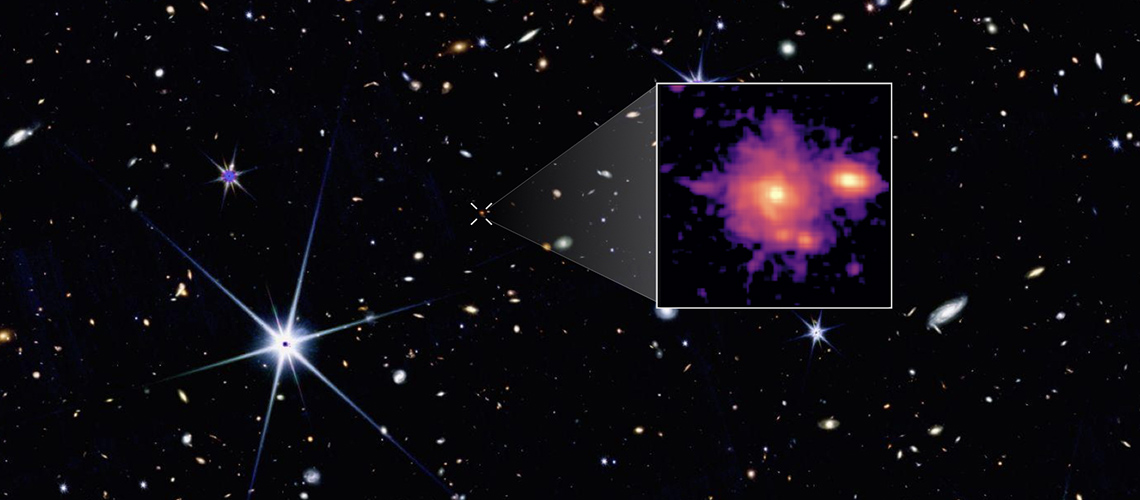

With its spiral arms and large star-forming disk, Zhúlóng resembles the Milky Way.

© NASA/CSA/ESA, PANORAMIC Team, M. Xiao (University of Geneva), C. C. Williams (NOIRLab), P. A. Oesch (UNIGE), G. Brammer (Niels Bohr Instititute)

Large spiral galaxies like the Milky Way were thought to take several billion years to form. Thus, during the first billion years of cosmic history, scientists expected to observe only small, chaotic, and irregularly shaped galaxies. However, JWST is beginning to reveal alternative scenarios. Its deep infrared imaging has uncovered surprisingly massive and well-structured galaxies much earlier than predicted, prompting astronomers to reconsider when and how galaxies took shape in the early Universe.

A Milky Way twin in the early Universe

Among these discoveries is a candidate spiral galaxy—one still awaiting confirmation—that would be the most distant ever identified. It was observed at a redshift corresponding to just one billion years after the Big Bang. Despite this early epoch, the galaxy exhibits an astonishingly mature structure: an old central bulge, a large star-forming disk, and spiral arms—features typically seen in galaxies much farther removed from the Big Bang.

"We named this galaxy Zhúlóng, meaning 'torch dragon' in Chinese mythology. In the myth, Zhúlóng is a powerful red solar dragon who creates day and night by opening and closing its eyes, symbolizing light and cosmic time," explains Mengyuan Xiao, a postdoctoral researcher at the Department of Astronomy in UNIGE's Faculty of Science and lead author of the study. "Zhúlóng stands out for its resemblance to the Milky Way, both in shape and in size and stellar mass."

Its disk spans over 60,000 light-years, comparable to our own galaxy, and contains more than 100 billion solar masses of stars. This configuration makes it one of the most compelling Milky Way analogs ever discovered at such an early time. It raises new questions about how massive, well-ordered spiral galaxies could have formed so soon after the Big Bang.

A serendipitous discovery

Zhúlóng was discovered through deep imaging from JWST's PANORAMIC survey, a large-scale extragalactic program led by Christina Williams (NOIRLab) and Pascal Oesch (UNIGE). PANORAMIC leverages JWST's unique "pure parallel" mode, an efficient strategy for collecting high-quality images while the telescope's primary instrument observes another target.

"This allows JWST to map vast areas of the sky, which is crucial for discovering massive galaxies, as they are incredibly rare," explains Christina Williams, an assistant astronomer at NOIRLab and principal investigator of the PANORAMIC program. "This discovery highlights the potential of pure parallel programs to uncover rare, distant objects that challenge galaxy formation models."

A story to rewrite

It was previously believed that spiral structures took billions of years to develop and that massive galaxies should only exist much later in the Universe, as they typically form through mergers of smaller galaxies. Pascal Oesch, associate professor at UNIGE's Department of Astronomy and co-principal investigator of the PANORAMIC program, explains: "This discovery shows that JWST is fundamentally changing our view of the early Universe."

Future observations with JWST and the Atacama Large Millimeter Array (ALMA) will help confirm its properties and shed more light on its formation history. Astronomers expect to find more galaxies of this kind as new JWST surveys unfold, providing deeper insights into the complex processes that shaped galaxies in the early Universe.