Follow us on Google News (click on ☆)

Nearly 1,500 years after its emergence, a team of researchers has solved part of this puzzle by discovering direct genetic evidence in a key region of the ancient world. This breakthrough not only illuminates the past but also helps to better understand the mechanisms of current pandemics.

By analyzing ancient DNA, scientists identified the Yersinia pestis bacterium in human teeth found in a mass grave in Jerash, Jordan. This site, located about 200 miles (320 km) from the presumed epicenter of the pandemic, provides unique testimony to the spread of the disease in the Byzantine Empire. The detected strains are nearly identical, indicating rapid and massive spread, consistent with historical accounts describing waves of sudden mortality.

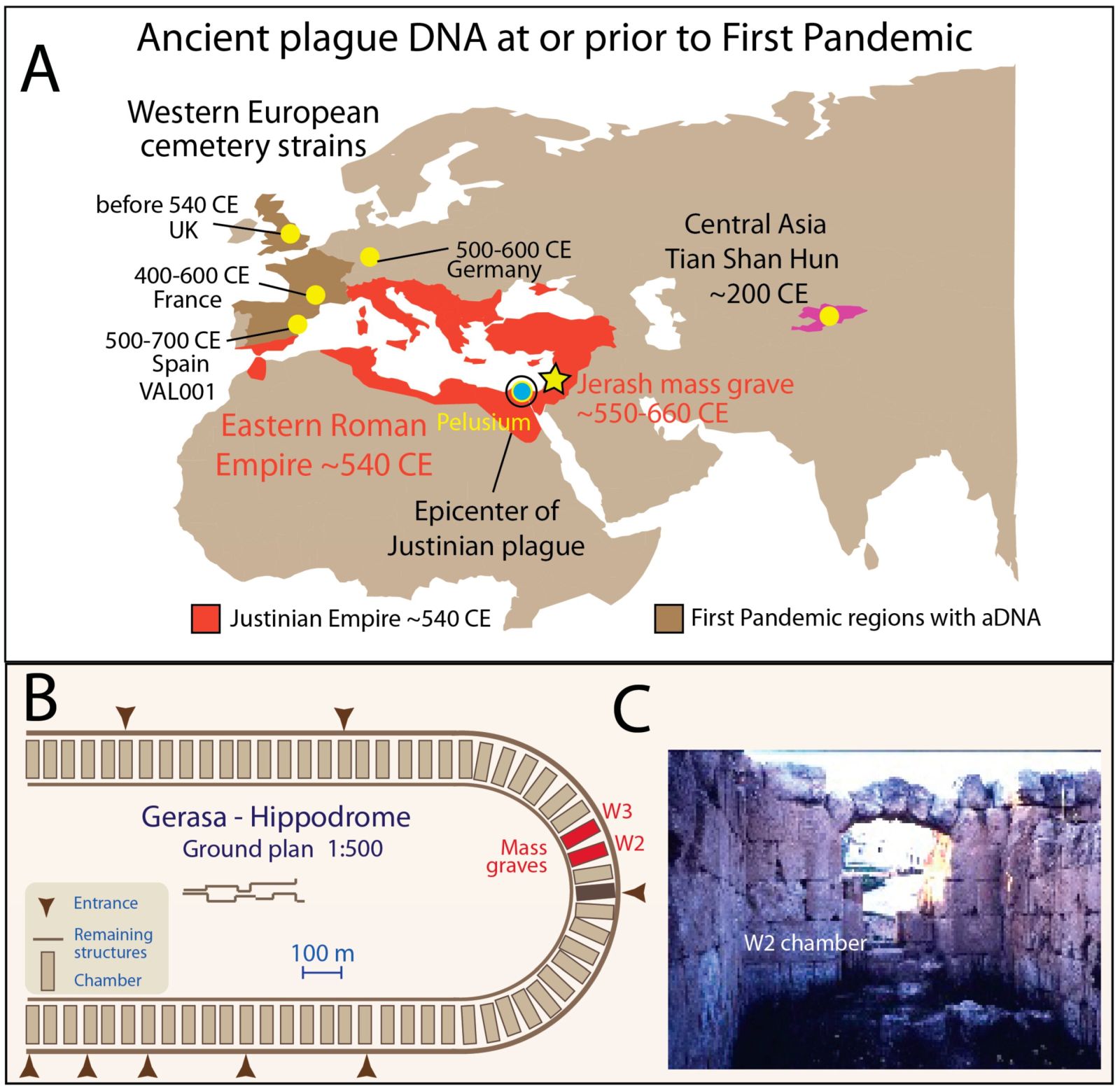

(A) Map showing regions of ancient DNA linked to the first pandemic. Jerash is marked by a star. Yellow dots indicate genetic evidence of Y. pestis, including the early Tian Shan Hun strain.

(B) Plan of the Jerash (Gerasa) hippodrome. The layout was redrawn based on Anton Ostrasz's illustration. Mass graves were discovered in chambers W2 and W3 of the abandoned Roman hippodrome.

(C) One of the chambers (W2) where the bodies were found.

Credit: Genes (2025). DOI: 10.3390/genes16080926

The Jerash excavations also show how an ancient Roman arena, once a venue for spectacles, was transformed into an improvised cemetery for victims. This repurposing illustrates how deeply the plague disrupted urban life, forcing residents to find emergency solutions. This sudden reuse of a public space highlights the fragility of large cities in the face of health crises – an observation that still resonates today.

A parallel study published in Pathogens analyzed several hundred ancient and modern Yersinia pestis genomes. It shows that plague pandemics, including the Black Death of the 14th century, do not all share the same origin. They emerged independently from animal reservoirs, rather than from a single ancestral strain. This pattern contrasts with that of COVID-19, which likely originated from a single spillover event of the virus to humans.

These results remind us that pandemics are not isolated accidents, but recurring phenomena linked to human exchanges and environmental changes. Researchers are now continuing their work in Venice, on the island of Lazaretto Vecchio, where infected people were quarantined, to understand how these ancient practices influenced pathogen evolution and the collective memory of societies.

The Justinian Plague: A Forgotten Pandemic

The Justinian Plague, which occurred between 541 and 750 AD, is considered the first historically documented pandemic. It is believed to have killed tens of millions of people, permanently weakening the Byzantine Empire and altering the history of the Mediterranean basin. Contemporary accounts describe intense fevers, swollen lymph nodes, and sudden mortality, characteristic of bubonic plague.

Until recently, the exact nature of this disease remained debated, as few direct traces had been found. The Jerash discovery provides strong genetic confirmation of Yersinia pestis' role. It allows for the reconstruction of the epidemic's spread routes through the commercial and military networks of the time.

Ancient DNA analysis was crucial: it enabled the extraction of intact genetic material from human remains dating back more than 1,500 years. These techniques open new perspectives for studying other ancient epidemics and for better understanding the evolution of infectious diseases over time.

Yersinia pestis: A Persistent Pathogen

Yersinia pestis is the bacterium responsible for plague, causing several major pandemics. It is transmitted mainly through infected fleas, which carry it from rodents to humans. The disease manifests primarily in two forms: bubonic plague, with painful buboes and a high mortality rate, and pneumonic plague, which is even more deadly and transmissible through the air.

Even today, Yersinia pestis has not disappeared. Isolated cases are reported each year, for example in the United States or Africa, as the bacterium survives in rodent populations that serve as natural reservoirs.

Recent genetic analyses show that plague epidemics do not originate from a single strain, but regularly re-emerge from these animal reservoirs. This dynamic explains why complete eradication of the disease is impossible. It also underscores the importance of continuous surveillance and appropriate public health measures to prevent new epidemic outbreaks.