🍖 Early humans were prey, not predators

Published by Cédric,

Article author: Cédric DEPOND

Source: Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences

Other Languages: FR, DE, ES, PT

Article author: Cédric DEPOND

Source: Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences

Other Languages: FR, DE, ES, PT

Follow us on Google News (click on ☆)

For decades, anthropology textbooks claimed that Homo habilis marked the turning point: that of a humanity capable of hunting, butchering, and eating meat, leaving behind its status as prey. But a team led by anthropologist Manuel Domínguez-Rodrigo from Rice University reveals a very different story.

Published in Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, his study demonstrates that about two million years ago, these early representatives of the Homo genus were still regularly devoured by leopards.

When technology reveals traces of the past

The innovation comes not only from the fossils but from how they were examined. Manuel Domínguez-Rodrigo's team applied artificial intelligence models to bones found in the Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania. These models were trained to recognize tooth marks left by various predators, from lions to crocodiles.

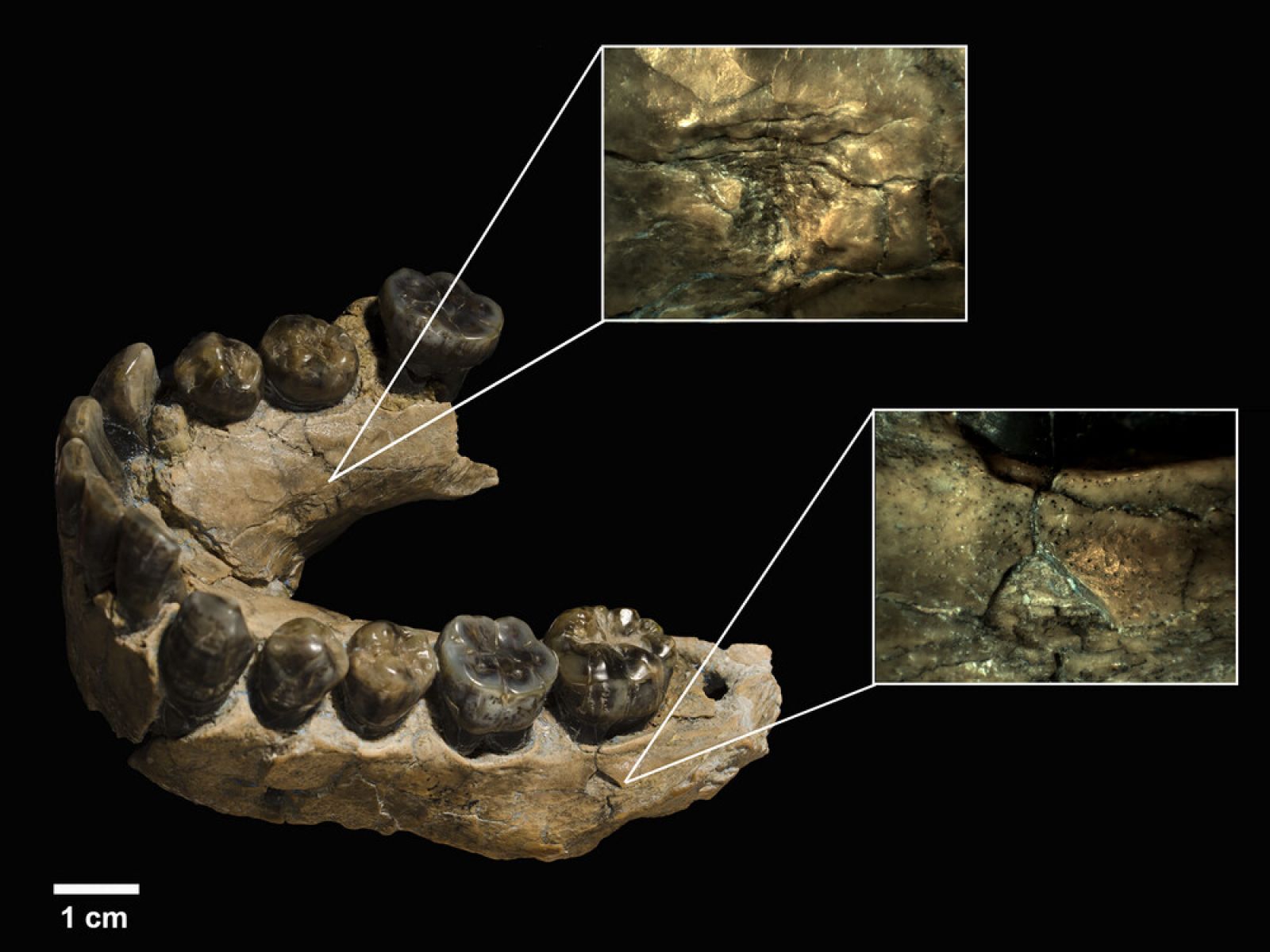

The results showed, with over 90% accuracy, that some bite marks came from leopards. These felines were not just scavenging: they were actively hunting these vulnerable hominids. This digital approach helped settle a long-standing debate: Homo habilis was not the dominant hunter once believed, but prey among others.

Example of bite marks analyzed on a prehistoric jaw.

A predator that wasn't one

The image of Homo habilis armed with tools and dominating the savanna is cracking. The studied traces suggest that this species remained fragile and exposed, despite its technical innovations.

Coexistence with Homo erectus, more robust and better adapted for walking, raises the question: who was truly the first human hunter? Researchers now lean towards Homo erectus, whose morphology offered better chances against predators.

This revision of the prehistoric hierarchy redraws the beginnings of our ascent. Humanity did not leap across the boundary between game and predator; it crossed it slowly, through increasingly elaborate survival strategies.

A new window on human evolution

This discovery illustrates how artificial intelligence is transforming the study of the past. By analyzing microscopic patterns, it can determine the species responsible for a bite mark millions of years old.

For Manuel Domínguez-Rodrigo, this method opens an unprecedented path: that of a paleontology enhanced by digital technology. The team now plans to extend these analyses to other fossils from East Africa to trace the precise moment when humans truly gained the upper hand over their predators.

The slow rise of the Homo genus thus appears as a long apprenticeship, marked by fear, flight, and survival. Human intelligence, before being conquering, was first that of an increasingly cunning prey.