Follow us on Google News (click on ☆)

This study, conducted by experts from the University of Chicago, Stanford, MIT, and other institutions, assesses the state of quantum hardware. It indicates that although functional systems exist, the real obstacles lie in scaling them up. Collaboration between academia, governments, and industry has accelerated progress, but the road to massive practical applications is still long.

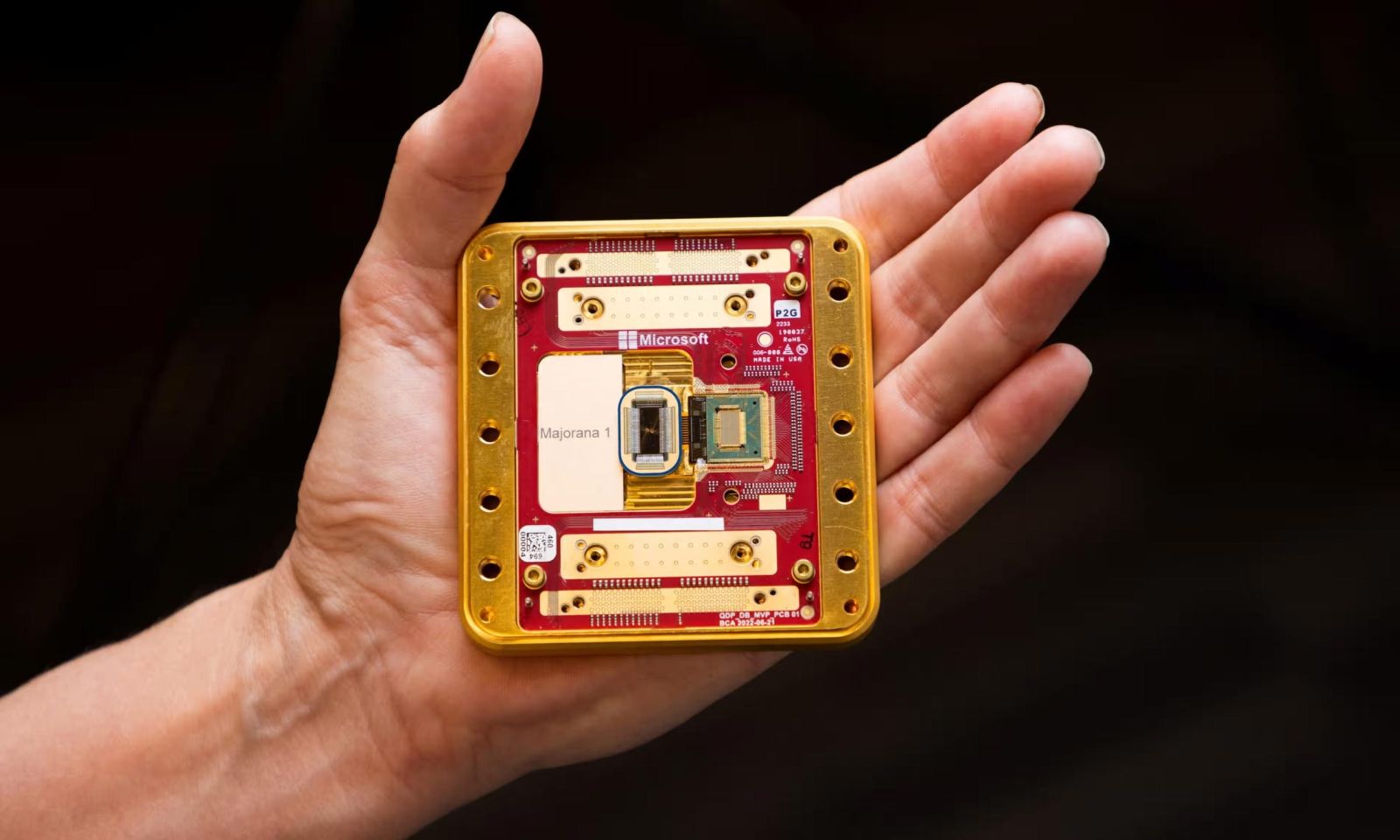

The Majorana 1 quantum processor.

Credit: Microsoft

To measure advancements, the authors compared six major quantum platforms, such as superconducting qubits (see below) and trapped ions. Using artificial intelligence models, they assigned technology readiness levels to each approach. These evaluations show that even the most advanced prototypes are far from the performance needed for, for example, large-scale chemical simulations requiring millions of qubits with low error.

One of the co-authors, William D. Oliver of MIT, explains that electronic components from the 1970s, although mature for their time, were limited compared to today's integrated circuits. Similarly, a high technology readiness level today does not mean quantum goals have been achieved, but that a modest demonstration has been made, still requiring substantial improvements.

The main obstacles identified include the mass fabrication of high-quality devices, the management of wiring and signals, and system control. These problems recall those encountered by computer engineers in the 1960s with the "tyranny of numbers." Mastering power, temperature, and automatic calibration is essential for scaling up.

The analysis shows the importance of learning from the history of computing. Innovations like lithography or new transistor materials took decades to move from the laboratory to industry. For quantum technologies, a systemic approach and shared scientific knowledge are vital, while cultivating patience, as has been the case with many historical breakthroughs.

Thus, although quantum technology is progressing rapidly, its full potential will depend on resolving persistent technical obstacles and a long-term vision. Researchers call for coordinated efforts to turn these promises into concrete realities, without haste.

Qubits: the fundamental units of quantum computing

Qubits are the basic building blocks of quantum systems, similar to bits in classical computing, but with unique properties. Unlike bits, which represent 0 or 1, qubits can exist in a superposition of states, enabling massive parallel calculations. This characteristic is exploited to solve difficult problems, such as molecular simulation or optimization, which exceed the capabilities of traditional computers.

Different technologies are used to create qubits, each with its advantages and disadvantages. For example, superconducting qubits operate at extremely low temperatures, while trapped ions are stable but require precise control. Spin defects in semiconductors offer potential integration with existing electronics, but their fabrication is delicate.

The choice of a platform depends on the targeted application, such as computation, communication, or sensing. Researchers are working to improve the coherence and fidelity of qubits, meaning their ability to maintain quantum information without error. Advances in materials and control techniques are essential for realizing practical large-scale systems.

Understanding these differences helps appreciate why scaling is so difficult. Each type of qubit imposes specific constraints in terms of temperature, noise, and connectivity, explaining the diversity of approaches explored in quantum research.

The technology readiness level (TRL) applied to quantum

The technology readiness level, or TRL, is a tool used to assess the development of an innovation, from theoretical design to operational implementation. It consists of nine levels, where level 1 corresponds to the observation of basic principles in the laboratory, and level 9 to a proven technology in a real-world environment. In the quantum field, this scale allows for an objective comparison of different platforms.

Applying TRL to quantum technologies shows that most systems are still at intermediate levels, between 4 and 6, where functional prototypes exist but require optimization. For example, superconducting qubits have reached a high TRL for computation, but their raw performance remains insufficient for large-scale industrial applications.

This evaluation helps identify critical steps for scaling, such as improving fabrication or reducing errors. It also warns against overly optimistic interpretation: a high TRL does not mean the technology is ready for massive deployment, but that it has passed an important stage in its development.

Looking at history, technologies like semiconductors had high TRLs at times when their capabilities were limited. This reminds us that the path to maturity is progressive, requiring constant iterations and sustained investment in research and engineering.