Follow us on Google News (click on ☆)

Using MRI and NMR techniques, a team from the Navier laboratory has demonstrated and measured this phenomenon of bound water transport, which also plays a role in regulating humidity in buildings using bio-based materials, as well as in wood drying processes. The results are published in the journal Physical Review Applied.

Illustration image Pixabay

When a plant or a piece of wood dries, it is first the water contained in the solid's pores, the so-called "free" water, that evaporates. But the material also contains "bound" water, housed within the cell walls. The mass of this bound water can represent up to 30% of that of dry wood. Until now, it was assumed that this water could move within the material, but no direct observation of bound water movement had been achieved: only the transport of overall moisture - pore water, vapor, and bound water - was measured.

A team from the Navier laboratory (CNRS/ENPC/Université Gustave Eiffel) conducted an experimental study that, for the first time, specifically demonstrated and characterized the transport of bound water in wood.

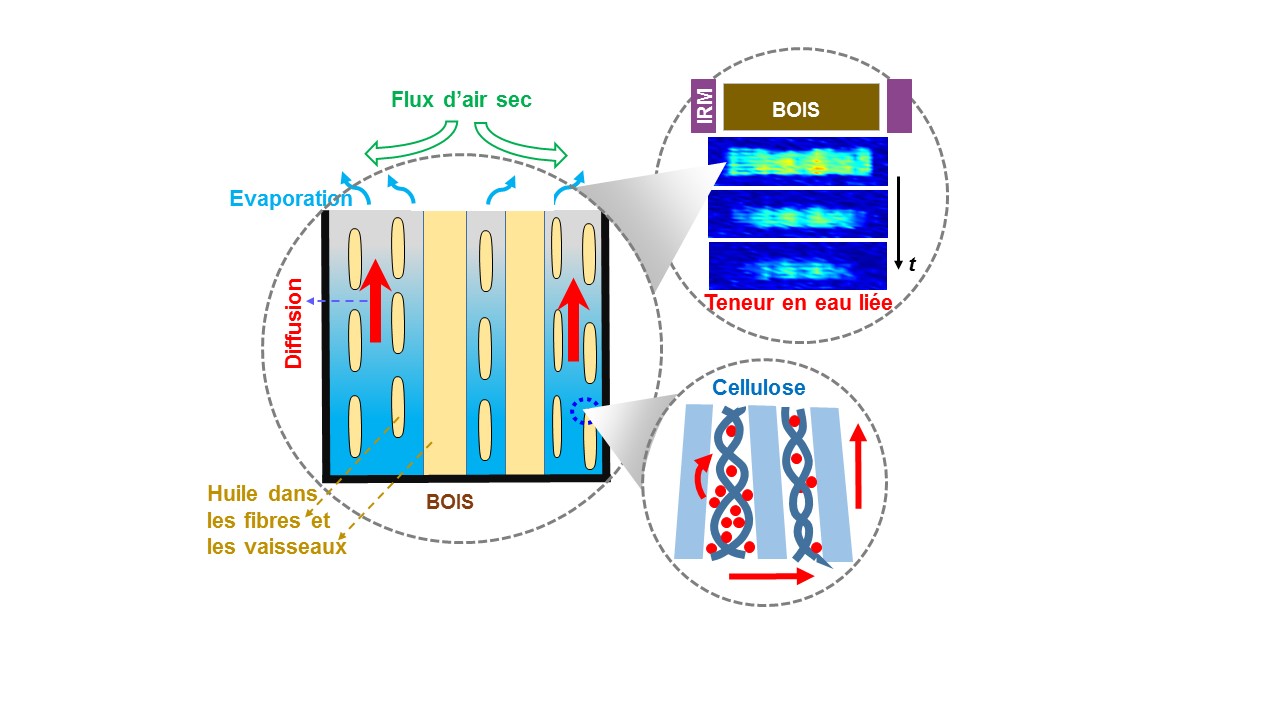

The diffusion of bound water in samples of oak, poplar, and fir wood was studied using MRI and NMR techniques, which allow visualization and measurement of water molecule movement. To do this, the samples were saturated with bound water for several weeks in a very humid atmosphere. The material's pores were then filled with silicone oil, limiting potential water movements to those of bound water within the solid phase.

Using MRI, the researchers were able to observe the diffusion of bound water molecules throughout the entire wood sample. NMR allowed quantification of the amounts of water moving. Similar results were obtained with the different types of wood, despite variations in material structure, and even across simple stacks of cellulose fibers. Counterintuitively, the bound water migration process appears to be independent of water concentration and direction (whereas wood is an anisotropic material).

The conclusion is that bound water, which is in fact very mobile, is transported spontaneously in wood under the influence of the slightest humidity concentration gradient. Indeed, variations in the diffusion coefficient with temperature allow identification of the activation energy that water molecules must overcome to diffuse, which is significantly higher than the gravitational potential energy. This explains why bound water can rise in a tree to great heights and help supply water to treetop leaves when they lack water.

The results of this study not only improve the understanding of water diffusion in plants. They also relate to humidity regulation in buildings using bio-based materials, wood drying processes, or extracting water from cellulose during paper manufacturing. At the Navier laboratory, the study continues, based on these novel results, with the aim of precisely describing how water diffuses through various bio-based construction materials containing plant fibers.

Diffusion of bound water in wood, within the solid phase surrounding voids, here filled with oil (central drawing). An activated process sets water molecules in motion within the amorphous zones of cellulose (bottom). The decrease over time of bound water content is observed by MRI (top).

© Luoyi Yan - Ph. Coussot/Navier Laboratory