🔬 A 1958 incongruous hypothesis on vitamin B1 now validated

Follow us on Google News (click on ☆)

Carbenes are particular chemical species where carbon has an electronic configuration that makes it very unstable. In 1958, chemist Ronald Breslow proposed that vitamin B1, or thiamine, could temporarily form an intermediate akin to a carbene during metabolic reactions. This hypothesis has long been difficult to confirm, because the water present in cells was seen as incompatible with the survival of such intermediates.

Walnuts are rich in vitamin B1.

Illustration image Pixabay

A team led by Vincent Lavallo designed a carbene protected by a molecular structure, based on chlorinated carboranes. This molecular "armor" physically prevents water from attacking the carbene's reactive areas, while adjusting the electronic properties to favor its stability. This approach combines steric shielding and electronic tuning, allowing the carbene to resist the aqueous environment.

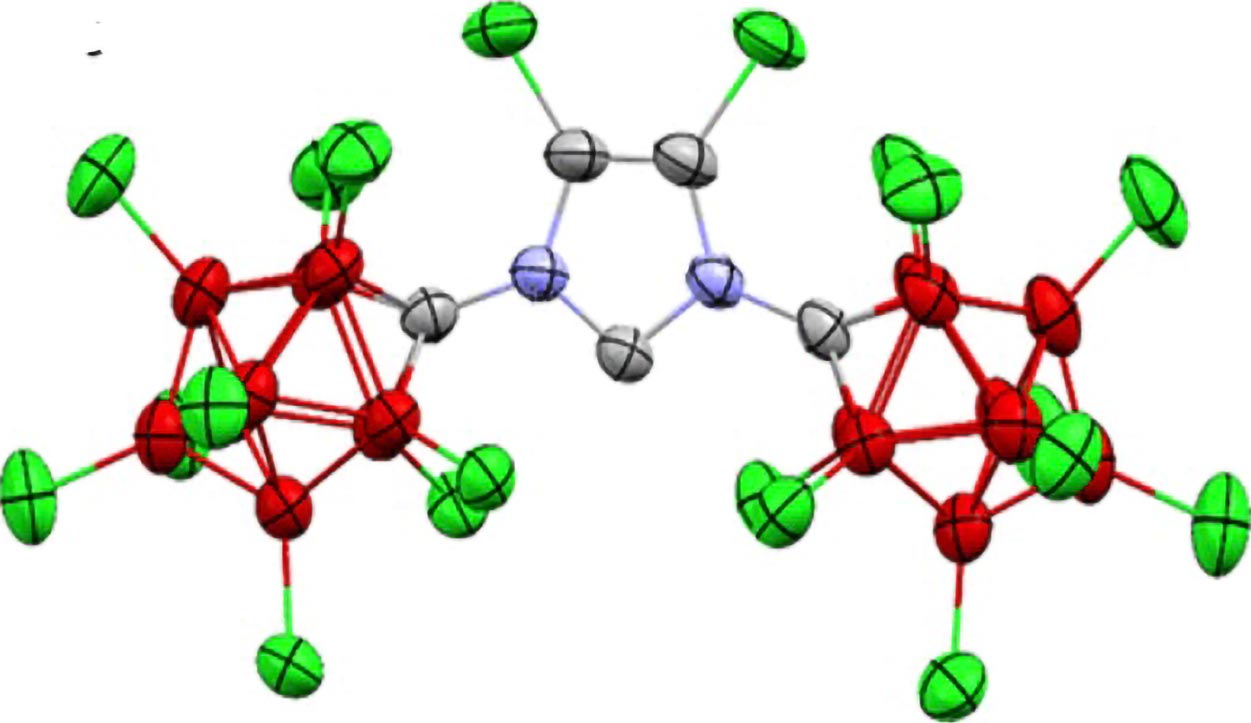

To confirm this stability, the scientists used nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy and X-ray crystallography. These techniques revealed characteristic signatures of the carbene and provided a direct image of its structure, showing the carbon nestled within a protected environment. According to Lavallo, it is the first time a carbene stable in water has been observed, an advance that validates Breslow's intuitions.

These results do not mean that enzymes use exactly this molecule, but they show that a carbene can exist in water if it is sufficiently protected. Enzymes often create microenvironments that control reactivity, specifically excluding water to stabilize high-energy intermediates. This principle allows for a better understanding of how thiamine might function in cells, despite the presence of water.

Furthermore, this discovery has implications for the chemical industry. Carbenes are used as ligands in metal catalysts for important reactions, such as the synthesis of pharmaceutical products. Currently, these processes frequently use toxic organic solvents, because water destroys the intermediates. If catalysts can be made stable in water, this paves the way for cleaner manufacturing methods, using water as the primary solvent.

Carbene stable in water visualized by X-ray diffraction.

Credit: Lavallo Lab/UCR

This approach also provides a new method for observing "invisible" reactive intermediates in chemical reactions. By protecting these fragile species, researchers could finally capture and study them directly, which could change our understanding of many mechanisms.

The ability of enzymes to manipulate microenvironments is common to many biological reactions. It relies on the three-dimensional structure of proteins, which guides molecular interactions. Understanding this principle helps design artificial catalysts inspired by nature, capable of operating under gentle and ecological conditions.