Follow us on Google News (click on ☆)

When the Chinese astronauts of the Shenzhou-20 mission inspected their spacecraft before leaving the space station, they discovered tiny cracks on the main porthole. An analysis quickly established that the impact of a space debris was the cause, making the return too perilous. This situation triggered the first emergency rescue mission of the Chinese manned space program, with the launch of a new vehicle to ensure the crew's return.

According to specialists, this event goes beyond a technical anecdote. An expert interviewed by Space.com sees in it a worrying signal about our collective ability to monitor what is in orbit. He indicates that postponing a crew's return out of caution actually shows a lack of precise and shared knowledge about the location of all these objects. Each new abandoned fragment adds more uncertainty, gradually reducing the safety margins for all space activities.

This uncertainty is not only a problem of statistics, but also of information sharing. The expert notes that to progress, nations and private companies would need to treat the reliability and transparency of data as an integral part of safety. Common orbital tracking systems and interoperable knowledge bases are necessary. The Shenzhou-20 episode could thus serve as a catalyst for improved space management, where missions would be evaluated on their ability to maintain order rather than add disorder.

Moreover, the multiplication of satellite constellations aggravates the problem. While some initiatives are conducted responsibly, others neglect the long-term consequences. Another specialist observes the increasing abandonment of rocket stages in orbits where they will remain for decades. He compares this attitude to a form of orbital climate change, where some operators prioritize short-term gains while ignoring well-documented effects. He estimates that targeted action on the most problematic objects could reduce the potential for creating new debris by 30%, but this willingness is still lacking.

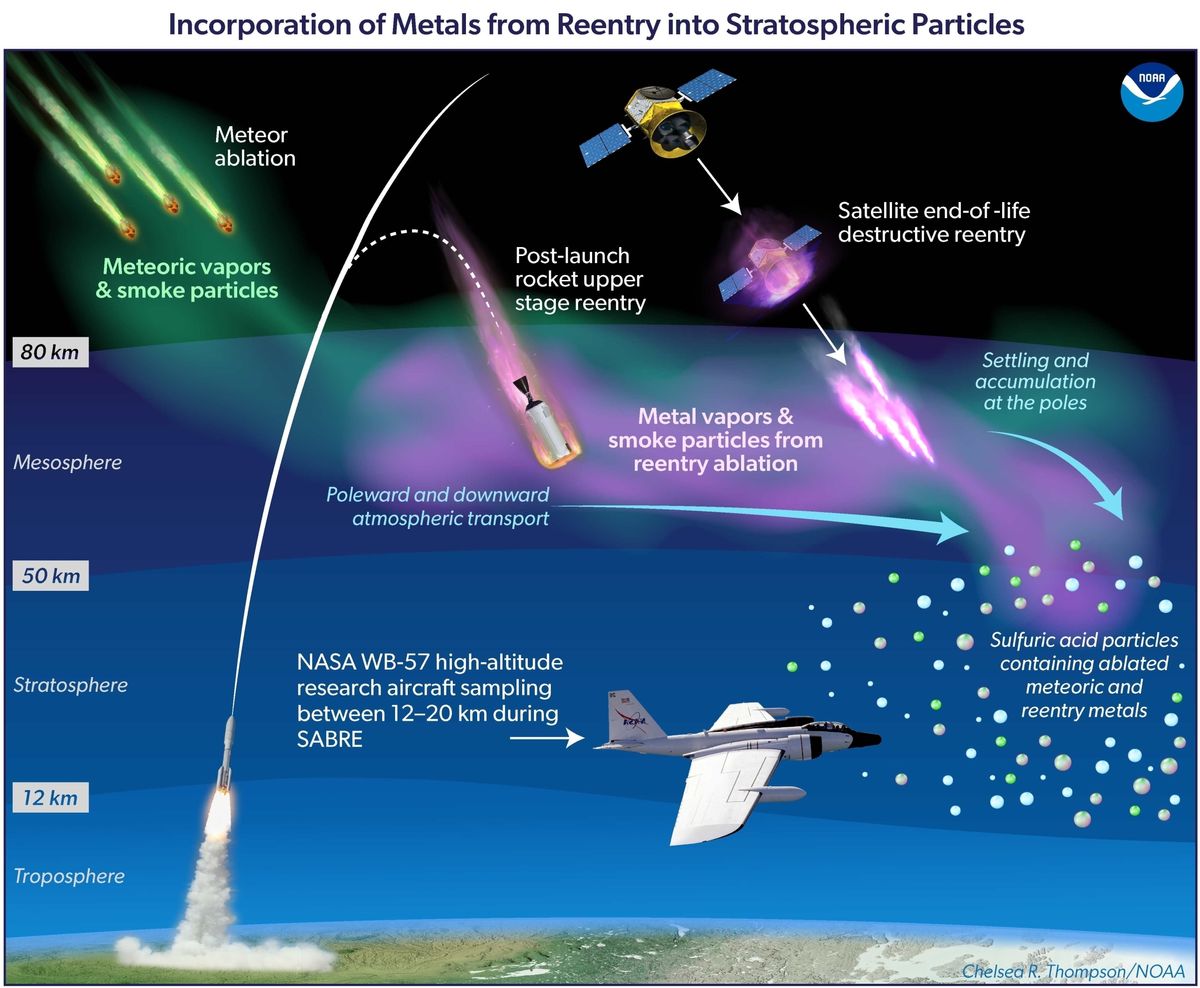

These concerns now go beyond the strictly spatial framework. A report from the United Nations Environment Programme identifies orbital debris as an 'emerging issue'. It warns about the environmental difficulties posed by the exponential growth of the space sector, which deploys thousands of new vehicles each year. The risks include atmospheric pollution during launches, emissions into the stratosphere, and the potential consequences of debris re-entries on the chemistry and climate of our atmosphere.

Illustration evoking the increase in launches and the anxiety related to the fallout of decommissioned space material.

Credit: Chelsea Thompson/NOAA

The Kessler Syndrome

When discussing space debris, a theoretical concept often comes up: the cascade effect. This scenario, formalized in the late 1970s, describes a situation where an initial collision between two objects in orbit generates a cloud of fragments. These new debris, moving at very high speed, in turn collide with other objects, thus creating an uncontrollable chain reaction.

The result would be the formation of a debris belt so dense that some orbits would become impracticable for decades, or even centuries. Space traffic and the use of satellites for communications, meteorology, or navigation would be greatly compromised. This perspective now guides efforts to develop rules of good conduct and cleaning technologies.

Not all debris in orbit falls back quickly. At altitude, where the atmosphere is very thin, air resistance is almost nil. An object placed in a high orbit can remain there for centuries before descending and burning up. This means that each new abandoned object contributes to a quasi-permanent stock, increasing the probability of future collisions.