🌌 A new way to determine the habitability of Earth-like planets

Follow us on Google News (click on ☆)

However, the environment close to these stars is often harsh, marked by extreme temperatures and powerful stellar flares. Despite these hostile conditions, these systems offer interesting perspectives for better understanding the formation and evolution of worlds located beyond our Solar System.

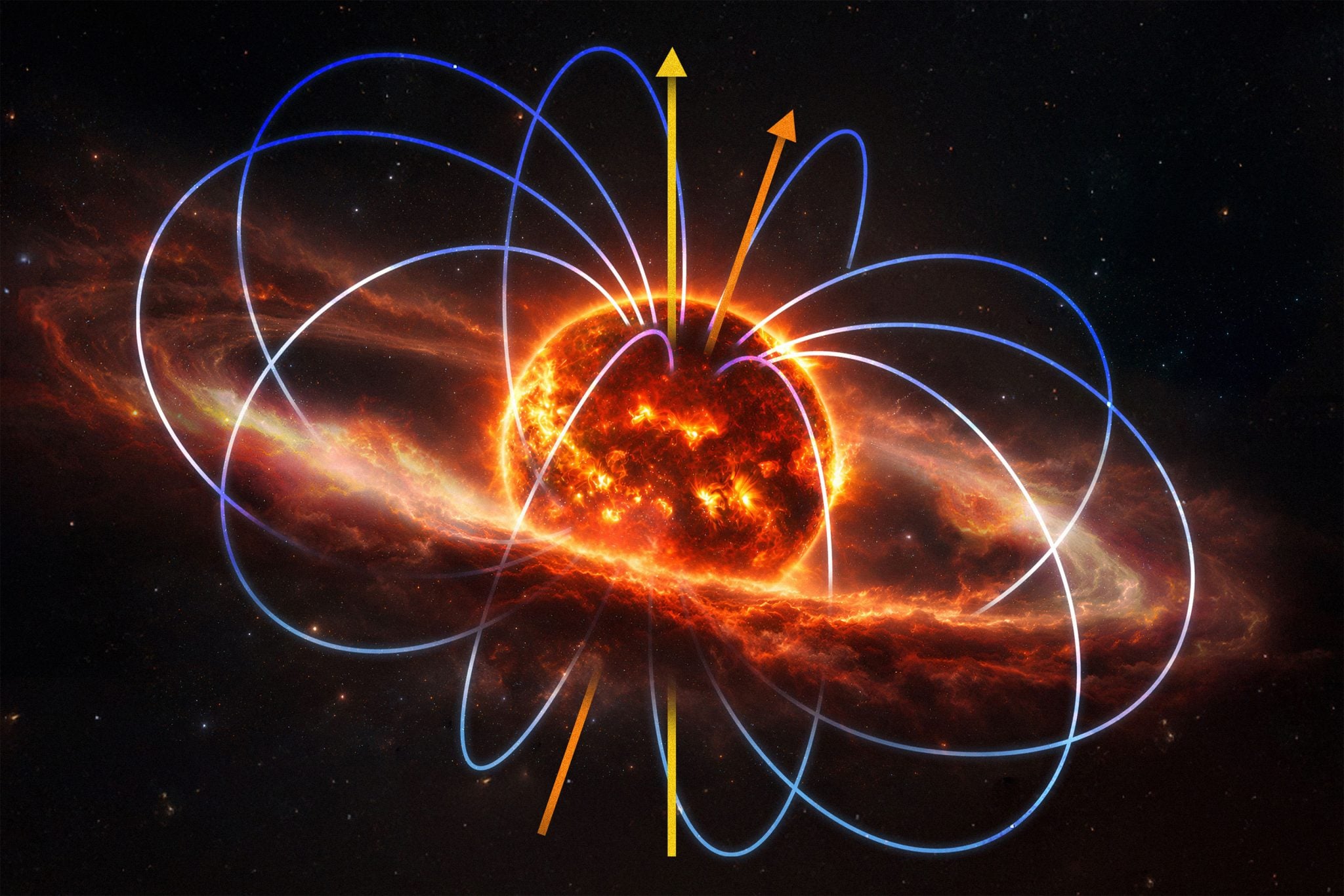

Artist's concept showing space weather around the M dwarf with visible magnetic field lines.

Credit: Illustration by Navid Marvi, courtesy of Carnegie Science

Scientists' attention has focused on a specific category of stars, named complex periodic variables. These young stars rotate rapidly on their own axis and display dips in brightness that repeat regularly. The origin of these variations had long remained unknown. Was it linked to spots on the star's surface or to an external phenomenon?

An in-depth analysis, using spectroscopic sequences comparable to films, has provided clarity. Researchers have established that these variations were associated with vast concentrations of cold plasma held in the star's magnetosphere. Under the influence of the magnetic field, this material is carried along by the stellar rotation and concentrates into a ring-like shape, evoking a cosmic doughnut.

This structure, called a plasma torus, is much more than a curiosity. It functions as a natural space weather station, providing astronomers with a means to indirectly explore the star's immediate environment. By studying the behavior of this torus, it becomes possible to obtain clues about the intensity of the magnetic field and the movement of charged particles. Estimates indicate that at least 10% of young M dwarfs would exhibit such characteristics.

For the future, one question remains: what is the origin of the matter composing this torus? Does it come from the star itself, perhaps ejected during flares, or from an external source, like a residual debris disk? Solving this mystery is important to better understand the evolution of these stellar systems. This work was presented at a meeting of the American Astronomical Society.

This approach thus reveals an original angle on the interactions between a star and its immediate environment. Understanding these mechanisms helps determine the conditions prevailing on orbiting planets, particularly regarding their potential to offer stable environments.

M dwarf stars and their planets

Also called red dwarfs, M dwarf stars are the most numerous stars in the Milky Way. Their mass, lower than that of the Sun, makes them less luminous and grants them exceptional longevity, potentially extending for thousands of billions of years. This very extended lifespan theoretically leaves a considerable amount of time for biological processes to develop on any worlds orbiting them.

Due to their faint glow, the so-called 'habitable' zone, where water could be liquid, is located much closer to the star than in our own system. A planet located in this region would therefore complete a full orbit in only a few days or weeks. This immediate proximity has significant repercussions on surface conditions.

This short distance also exposes these planets to a more intense stellar environment. M dwarfs are known for their high magnetic activity, particularly during their youth, which results in frequent and powerful flares. These events can subject planetary atmospheres to a bombardment of radiation and energetic particles.

Nevertheless, the extreme abundance of M dwarfs makes them prime targets in the search for potentially habitable planets. Studying how they shape their environment thus represents an important phase in preparing future observations and refining the interpretation of collected data.