Follow us on Google News (click on ☆)

From cells derived from colon tumors, scientists from the University of Geneva (UNIGE) first identified the criteria affecting the risk of metastases, then gene expression signatures allowing to assess their probability. The team then created an artificial intelligence tool (MangroveGS) capable of transforming this data into predictions for many cancers with unmatched reliability. These results, published in Cell Reports, pave the way for more precise care and the discovery of new therapeutic targets.

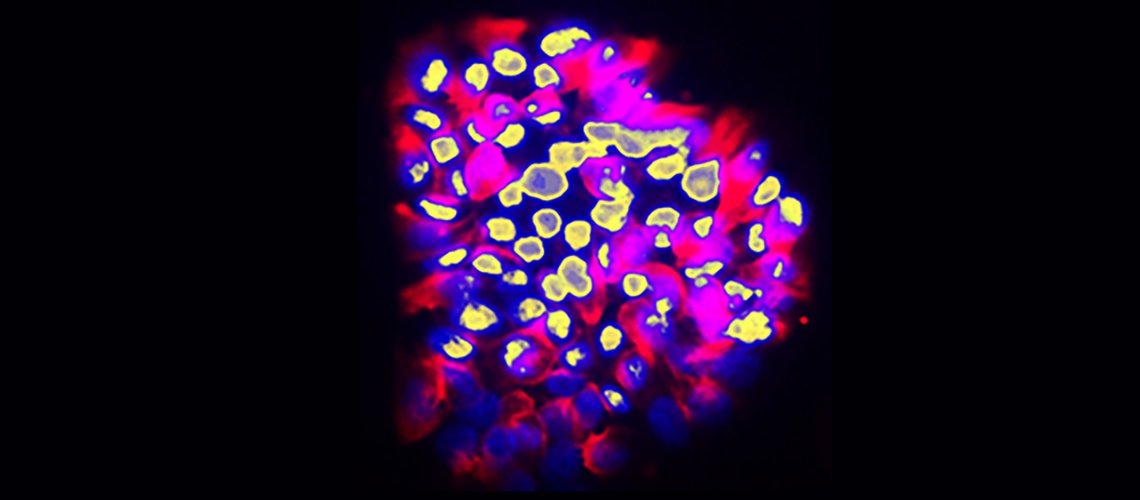

Human colon cancer cells with invasive behavior. The cell nuclei are in yellow and the cell bodies in red. The finger-like protrusions of invasive cells are in the upper region.

© Ariel Ruiz i Altaba, UNIGE

"The origin of cancer is often attributed to 'anarchic cells'," explains Ariel Ruiz i Altaba, full professor at the Department of Genetic Medicine and Development of the Faculty of Medicine at UNIGE, who led this work. "However, cancer should rather be understood as a diverted form of development." Indeed, under the effect of genetic and epigenetic changes, programs suppressed during the development of the organism and tissues reawaken to give rise to a tumor.

Thus, far from being an anarchic accident, cancer follows an ordered program. "The whole challenge is therefore to find the keys to grasp its logic and form. And, in the case of metastases, to identify the characteristics of the cells that will separate from the tumor to create another elsewhere in the body.

Tracking metastatic cells

Metastases remain the main cause of mortality in most cancers, particularly for colon, breast, or lung cancers. Currently, the first detectable sign of the metastatic process is the presence, in the blood or lymphatic system, of circulating tumor cells. But it is already too late to prevent their dissemination. Moreover, while the mutations that lead to the formation of original tumors are well understood, no single genetic alteration can explain why, in general, some cells migrate and others do not.

"The difficulty is to be able to detail the complete molecular identity of a cell — an analysis that destroys it — while observing its function, which requires it to remain alive," explains Professor Ruiz i Altaba. "For this, we isolated, cloned, and cultured tumor cells," adds Arwen Conod, senior assistant at the Department of Genetic Medicine and Development of the Faculty of Medicine at UNIGE and co-first author of this study. "These clones were then evaluated in vitro and in a mouse model to observe their ability to migrate through a true biological filter and generate metastases."

The analysis of the expression of several hundred genes, performed on about thirty clones from two primary colon tumors, allowed the identification of gene expression gradients closely linked to their migratory potential. In this context, the precise evaluation of metastatic potential does not depend on the profile of a single cell, but on the sum of interactions between related cancer cells that form a set.

An ultra-reliable prediction algorithm

The obtained gene expression signatures were integrated into an artificial intelligence model developed by the Geneva team. "The major novelty of our tool, called 'Mangrove Gene Signatures' or 'MangroveGS', is to exploit tens, even hundreds of gene signatures. This makes it particularly resistant to individual variations," explains Aravind Srinivasan, assistant at the Department of Genetic Medicine and Development of the Faculty of Medicine at UNIGE and co-first author of this study.

After training, the model achieved an accuracy close to 80% for predicting the occurrence of metastases and recurrences of colon cancer, a result far superior to existing tools. Moreover, the signatures derived from colon cancer can also predict the metastatic potential of other cancers, such as stomach, lung, or breast cancer.

An important step for clinic and research

Thanks to MangroveGS, tumor samples are sufficient: the cells can be analyzed and their RNA sequenced at the hospital, then the metastatic risk score is quickly transmitted to oncologists and patients from an encrypted Mangrove portal, responsible for analyzing anonymized data.

"This information will allow avoiding overtreatment of low-risk patients, thus limiting side effects and unnecessary costs, while intensifying surveillance and treatment for those whose risk is highly elevated," adds Ariel Ruiz i Altaba. "It also offers the possibility to optimize the selection of participants in clinical trials, which reduces the number of required volunteers, increases the statistical power of studies, and brings therapeutic benefit to patients who need it most."

This work was carried out notably with the support of the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF), the Swiss Cancer Research Foundation, and the DIP of the State of Geneva.