Follow us on Google News (click on ☆)

This fragmentation is directly linked to the comet's close passage near the Sun in October 2025. The gravitational force of our star and the solar wind, a constant stream of particles, exerted significant pressure on this aggregate of ice and dust. These extreme conditions caused it to dislocate into several pieces, as evidenced by the images.

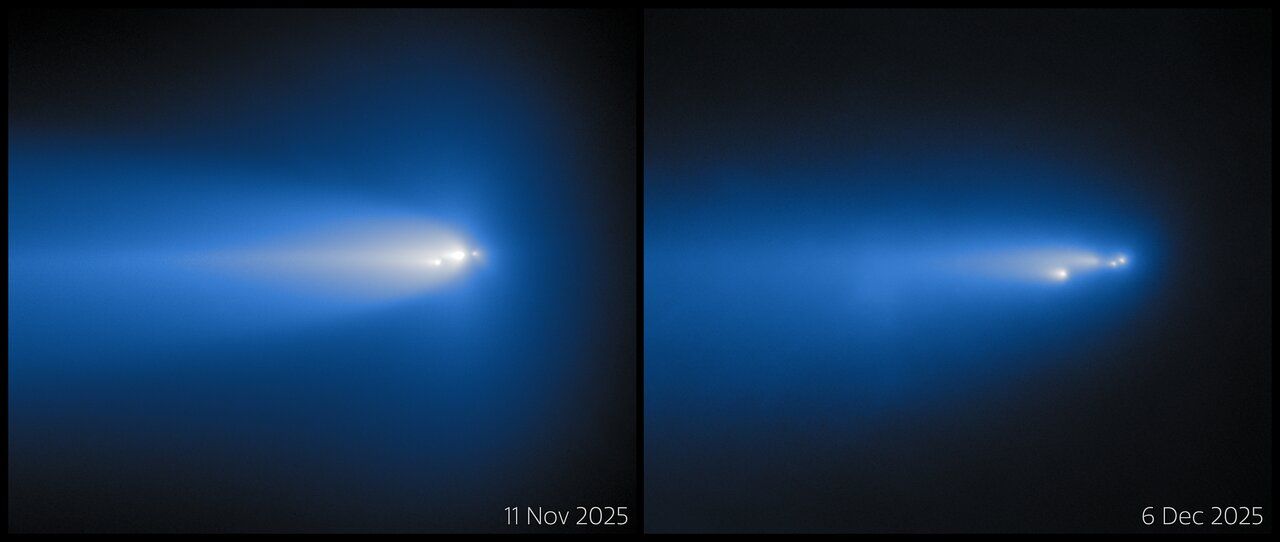

Comet C/2025 K1 (ATLAS) in the process of fragmenting, seen on November 11, 2025 (left) and December 6, 2025 (right) by the Gemini North telescope.

Credit: International Gemini Observatory/NOIRLab/NSF/AURA/B. Bolin

In parallel, images by astronomer Gianluca Masi, published on the Virtual Telescope Project website, notably showed three, or even four distinct fragments. For its part, the Asiago Observatory in Italy also confirmed the presence of two main pieces separated by about two thousand kilometers (approximately 1,240 miles). These multiple observations help reconstruct the chronology of the disintegration.

This comet, discovered in May 2025 by the ATLAS alert system, most likely originates from the Oort Cloud. This distant region, located far beyond the orbit of Neptune, is thought to contain billions of similar icy bodies. These objects represent prime targets for scientists, as they constitute relatively unaltered remnants from the formation of the Solar System.

Indeed, so-called 'long-period' comets, like C/2025 K1, are less affected by solar heat and radiation than more regular visitors like Halley's Comet. Their study thus offers a purer glimpse into the conditions that prevailed several billion years ago, when the planets were forming.

Why do comets fragment?

Comets are not solid blocks of rock, but rather fragile aggregates, often compared to 'dirty snowballs'. Their nucleus, which can range from a few hundred meters to several tens of kilometers across, is a loosely compacted mixture of volatile ices and dust. This structure is relatively fragile.

When a comet approaches the Sun, the intense heat causes the sublimation of surface ices: they pass directly from the solid to the gaseous state. This outgassing creates the comet's spectacular tail, but it also exerts pressure from the inside out. This force can crack the nucleus if it is not coherent enough.

The Sun's gravitational force, particularly strong during a very close approach (perihelion), exerts a differential pull on the parts of an irregular or already fractured nucleus. This "tidal effect" can accentuate existing faults and ultimately separate pieces, as observed for C/2025 K1.

The combination of heat, outgassing, and solar tidal forces therefore constitutes the main fragmentation mechanism. This process is natural and common on a cosmic scale. Observing such an event in real time allows astronomers to better model the internal structure and mechanical strength of these objects.