Follow us on Google News (click on ☆)

This major scientific breakthrough, the fruit of an international collaboration within the 4D Nucleome Project, unveils the three-dimensional and dynamic organization of the human genome. By studying embryonic stem cells and fibroblasts, researchers have captured the principles governing how chromosomes fold and interact within the confined space of the nucleus, directly influencing gene activity.

The Intimate Architecture of the Nucleus

Contrary to the linear image inherited from sequencing, DNA adopts an extremely organized spatial conformation. It forms loops, domains, and compartments whose geometry conditions access for the molecular machinery responsible for reading genetic information. This 3D structure is not random; it determines which genes are activated or repressed, thus sculpting the identity and function of each cell.

To map this landscape, scientists merged data from several cutting-edge genomic technologies. This integrative approach allowed them to overcome the limitations of each method in isolation. The result is a set of high-resolution models that capture architectural variability from one cell to another, offering a more nuanced and realistic view of intranuclear life.

The work, published in Nature, identified over 140,000 interactions in the form of chromatin loops per cell type. These loops physically bring together distant DNA sequences, such as genetic switches with the genes they control. The precise map of these molecular anchor points is a key to understanding the fundamental mechanisms of gene regulation.

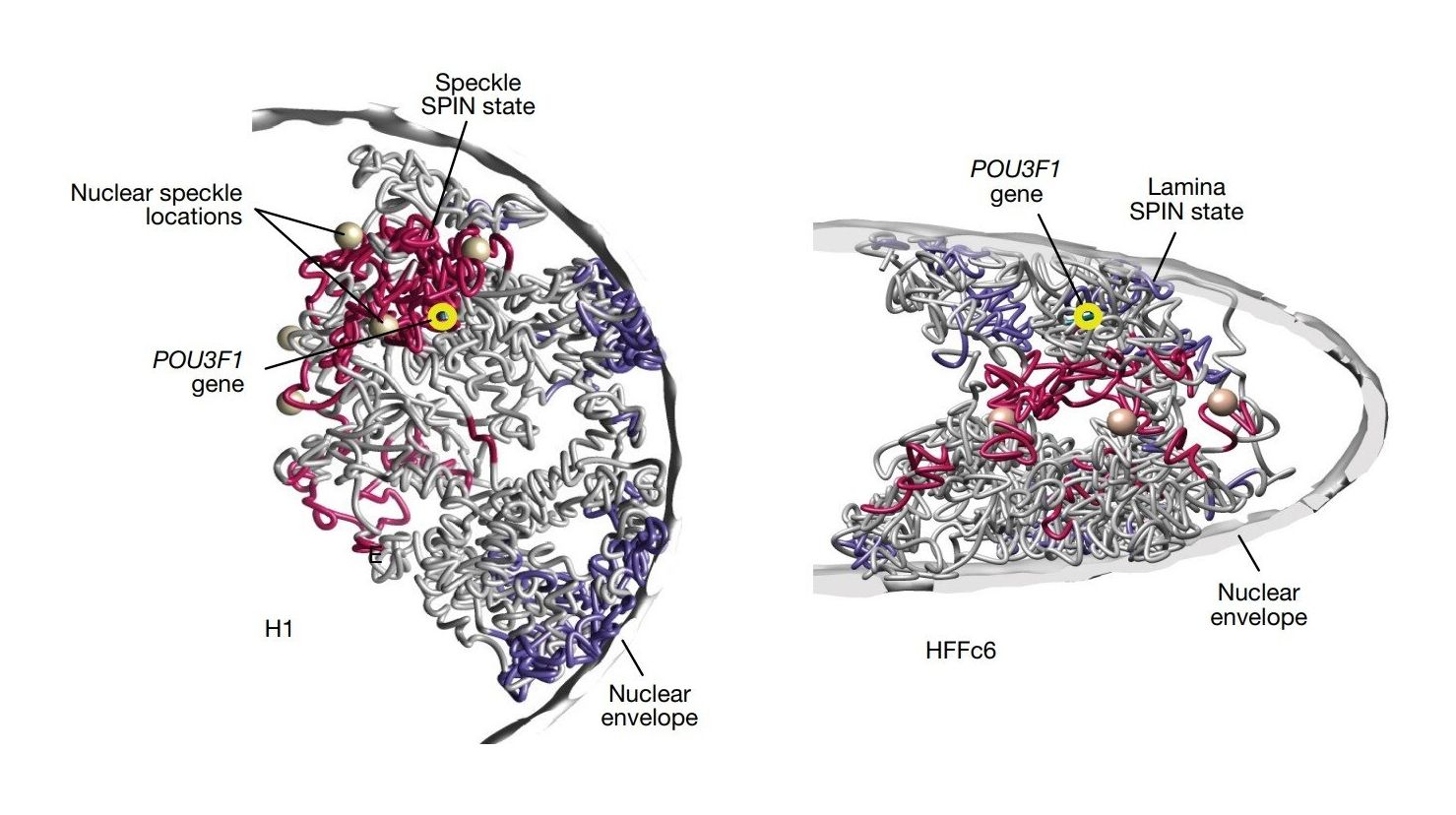

Representative single-cell 3D structures of chromosome 1 in H1 cells (left) and HFFc6 cells (right).

Credit: Nature (2025)

Predicting the Effects of Mutations by Shape

One of the most significant contributions of this study lies in the development of computational tools capable of predicting how a DNA sequence will fold. This advance opens the perspective of forecasting the impact of genetic variations on genome structure without resorting to laboratory experiments. It is essential for interpreting mutations found in non-coding regions, often implicated in diseases.

Indeed, many variations associated with pathologies like cancer or developmental disorders do not directly modify a gene but likely disrupt its 3D structural environment. The new mapping provides a framework for identifying which genes might be affected by these long-range alterations, thus linking cryptic mutations to their biological consequences.

The researchers also established a rigorous methodological guide by comparing the performance of different genomic mapping techniques. This reference allows the scientific community to choose the most suitable tools for studying a specific aspect of nuclear organization, whether loops, chromosomal domains, or positioning within the nucleus.

The ultimate goal of this work is translational. Having observed structural anomalies of the genome in leukemias or brain tumors, the team now aims to explore how to pharmacologically target this architecture, for example with epigenetic inhibitors. Understanding the shape of the genome could thus lead to new diagnostic and therapeutic strategies.