Follow us on Google News (click on ☆)

Artist's impression of the Peruvian coast during the Miocene, with the current desert below.

© Matthieu Carré

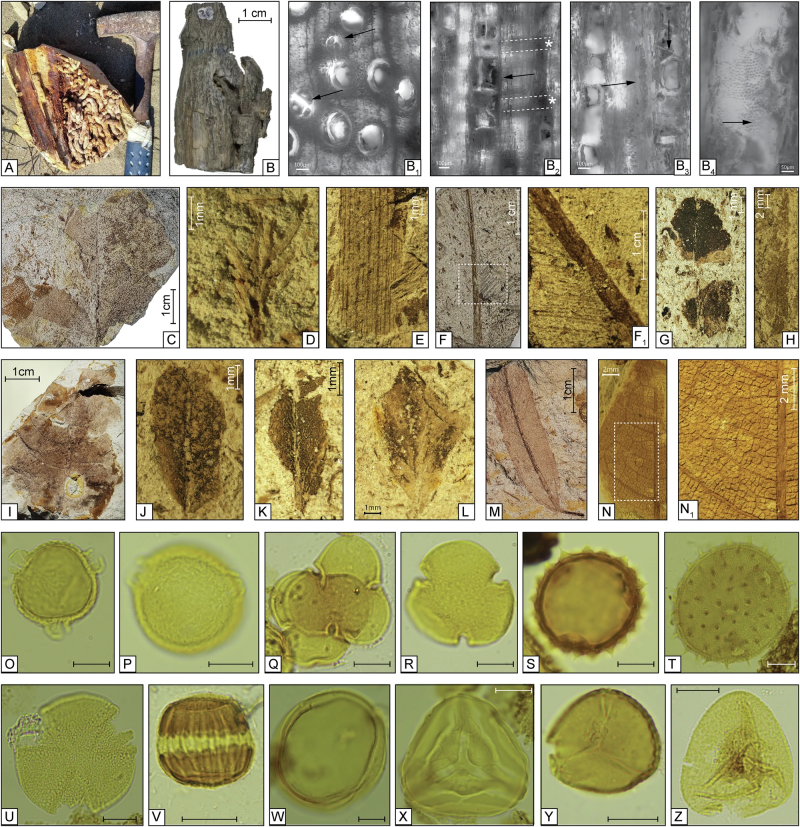

Researchers from LOCEAN and Cayetano Heredia University (Peru) discovered exceptionally well-preserved fossil leaves and pollen grains in an ancient geological layer called the Pisco Formation. These plant remains prove that a dry tropical forest once covered this region.

Today, this South American coastline is one of the driest places on Earth, squeezed between the cold Pacific waters and the high Andean peaks. But in the late Miocene, about 8 million years ago, it was home to trees, shrubs, ferns, and even palm trees. A striking contrast with the current desert!

This vegetation indicates the climate was much more humid then, with rainfall up to three times heavier than today in the same area.

An unexpected discovery

It all began by chance thanks to Diana Ochoa, a young Peruvian researcher. While studying marine sediments known for their marine animal fossils (like giant sperm whales or megalodons), she stumbled upon some fossilized tree leaves.

These findings led to an in-depth study of fossil pollen, revealing extinct flora with no modern equivalent. By analyzing soil layers, scientists estimated annual rainfall at the time was about 36 mm (1.4 inches), compared to just 9 mm (0.35 inches) today.

Fossilized remains of leaves, wood, and pollen found in the Pisco Formation.

A glimpse of the future?

At that time, atmospheric CO₂ levels already exceeded 400 ppm — a threshold we recently crossed again (it was 320 ppm in 1960 vs. 420 ppm today). The late Miocene climate could thus serve as a natural model for imagining the future.

While climate change is often thought to make deserts even drier, this study suggests the South Pacific Desert might instead experience phases of regreening. This would be linked to more intense El Niño events, a climate phenomenon that sometimes brings heavy rains.

If the devastating effects of these rains were better managed through adapted infrastructure, they could also offer new opportunities for nature and agriculture in these extremely dry areas, where nearly 17 million people live today.