🌱 What if life emerged in jelly?

Follow us on Google News (click on ☆)

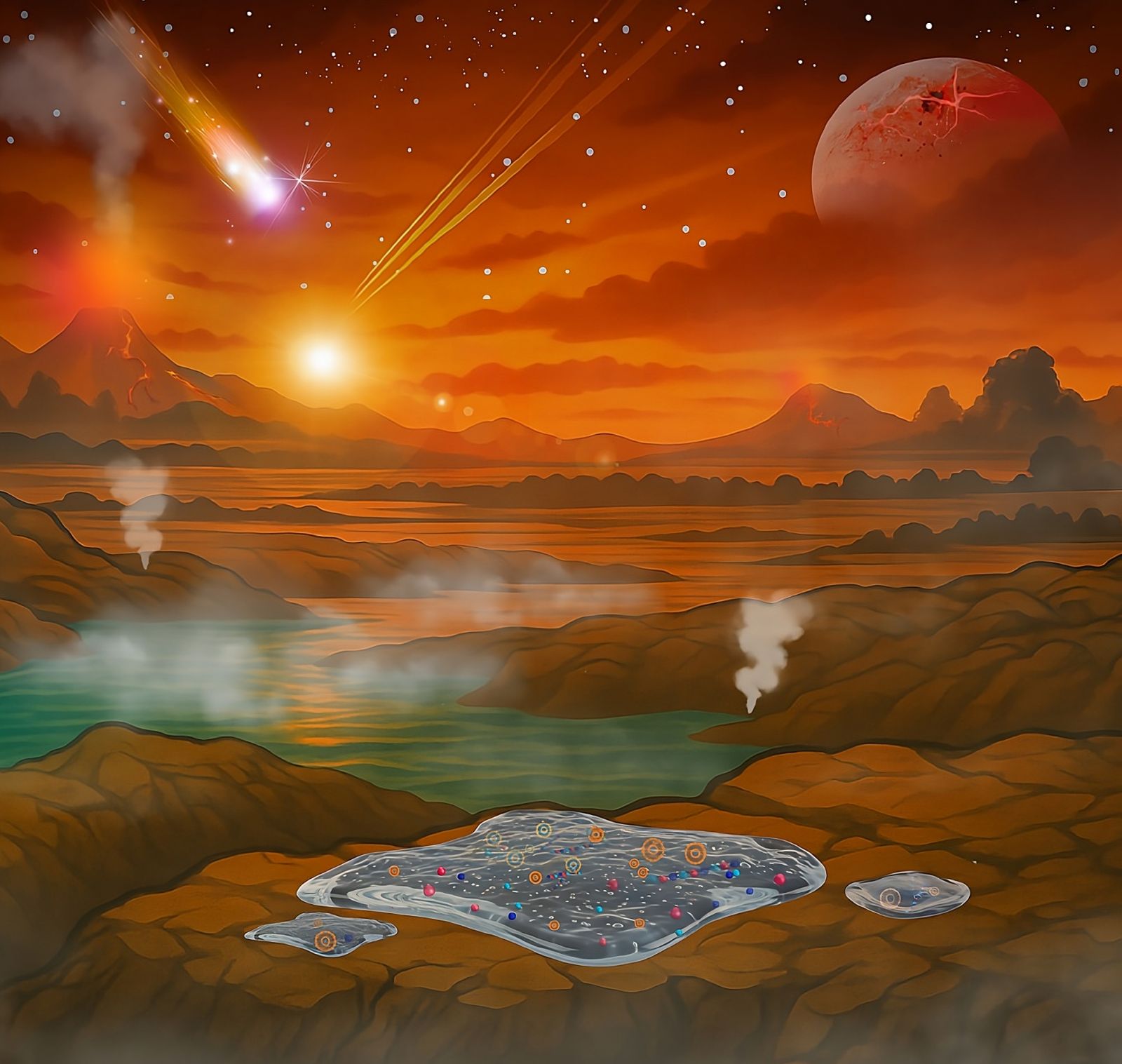

Their model, named the 'primordial prebiotic gel,' describes how these semi-solid substances, similar to present-day microbial biofilms, could have formed on rock surfaces or in primitive ponds. Building on soft matter chemistry, the scientists estimate that these gels offered an ideal structure to trap and concentrate organic molecules. This work was presented in the journal ChemSystemsChem.

Inside these gelatinous matrices, chemical reactions could have proceeded more efficiently. Indeed, gels allowed for selective retention of compounds and protection against environmental variations. Consequently, chemical systems precursor to metabolism and replication could have gradually emerged, thereby laying the foundation for biological evolution.

As indicated by Tony Z. Jia, a professor at Hiroshima University, this theory emphasizes the role of gels, which is often overlooked in origin-of-life research. To support this proposal, the team synthesized various studies to establish a coherent narrative where these primitive structures play a central role. According to Kuhan Chandru, a researcher at the National University of Malaysia, this is one proposal among others, but it opens a new path.

This perspective also opens new avenues for the search for life elsewhere in the Universe. For example, on other planets, analogous gels, called 'xeno-films,' might exist with different chemical compounds. Consequently, the detection of such structures, rather than specific molecules, could become an objective for space missions, thereby broadening the methods used by astrobiologists.

The researchers now plan experiments to recreate these gels under conditions similar to those of primitive Earth. They hope to better understand their properties and inspire other work in this field, as desired by Ramona Khanum, co-author of the study. These investigations may shed light on the steps that led to the emergence of life.

Prebiotic chemistry: from simple building blocks to complexity

Prebiotic chemistry explores the chemical processes that preceded the appearance of life on Earth. This discipline focuses on the formation of organic molecules from simple elements present in the primitive environment, such as water, methane, or ammonia. Experiments, like the Miller-Urey experiment, have shown that electrical sparks in a reducing atmosphere can generate amino acids, the building blocks of proteins.

These molecules then had to assemble into more elaborate structures. Prebiotic chemistry examines how reactions could have occurred in an orderly fashion, despite an often chaotic environment. Factors such as the presence of clay minerals or hydrothermal vents could have catalyzed these processes, providing surfaces for molecular organization.

The next step concerns the emergence of biological functions, like information replication or energy metabolism. Current theories consider various scenarios, including the gel scenario, to explain how these functions could have arisen in a non-living environment. This discipline continues to evolve constantly, integrating data from geology and biology.

Understanding prebiotic chemistry also helps define the conditions necessary for life elsewhere. By identifying the important steps on Earth, scientists can better target conducive environments on other planets or moons, such as Mars or Europa.