Follow us on Google News (click on ☆)

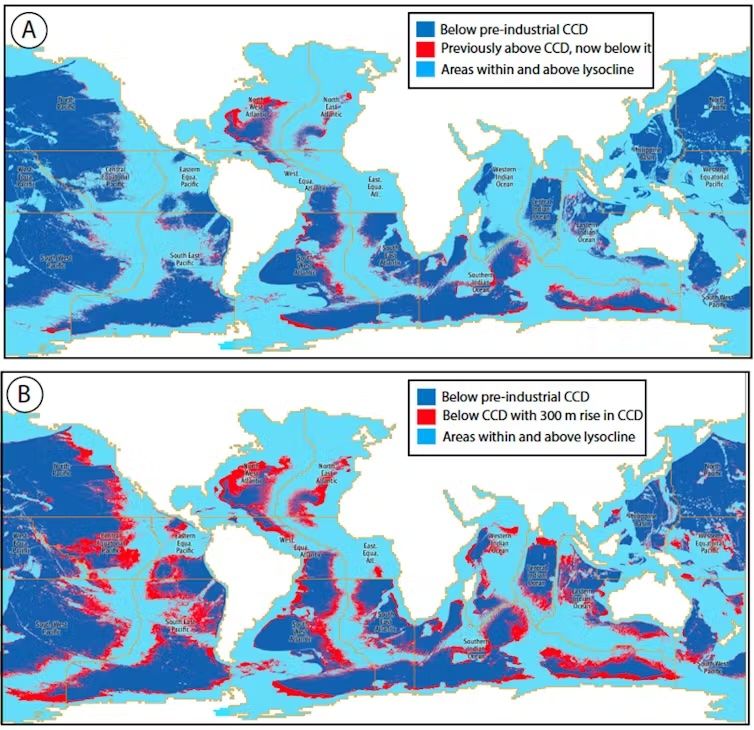

This critical zone is referred to as the carbonate compensation depth. While much attention has been given to the acidification of surface waters, the situation in deeper waters is equally concerning. The increase in dissolved carbon dioxide in the ocean lowers the water's pH, making this zone increasingly corrosive to calcium carbonate, leading to a rapid expansion of this corrosive region.

This expansion is evident in the upward shift of the lysocline, the transition zone where calcium carbonate becomes unstable and begins to dissolve. An elevation of just a few feet in this zone can significantly increase areas unsaturated in carbonate, making sediments unstable and prone to dissolution.

The rise in the carbonate compensation depth not only alters the chemical composition of the sediments but also the ecosystems that inhabit them. Species that depend on calcium carbonate for their structures, such as soft corals and starfish, are replaced by species like sea anemones and sea cucumbers that can survive in more acidic waters.

These maps show changes in oceanic areas exposed to corrosive deep waters across 17 different regions.

Credit: Mark John Costello and Peter Townsend Harris, CC BY-SA

Furthermore, this increasing acidification affects nations unevenly. Island states are particularly vulnerable, such as Bermuda, where a 1,000-foot (300 meters) rise in this critical depth corresponds to 68% of their exclusive economic zone. In contrast, countries like the United States and Russia, with wider continental shelves, see a smaller proportion of their territory affected.