❄️ Antarctica is mysteriously getting saltier

Published by Cédric,

Article author: Cédric DEPOND

Source: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

Other Languages: FR, DE, ES, PT

Article author: Cédric DEPOND

Source: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

Other Languages: FR, DE, ES, PT

Follow us on Google News (click on ☆)

Since 2015, the record reduction of Antarctic sea ice, equivalent to the area of Greenland, coincides with a sudden increase in ocean salinity. An international team, led by the University of Southampton, revealed this concerning mechanism through satellite data and in-situ measurements.

A vicious cycle: salt and heat

Normally, the ocean consists of layered zones: cold, less salty water stays at the surface, while warmer, saltier water remains at depth. This natural separation prevents deep heat from rising.

But when the surface becomes saltier, this order breaks down. Surface water starts sinking and mixes the layers. Deep heat then rises toward the surface, melting ice from below more rapidly.

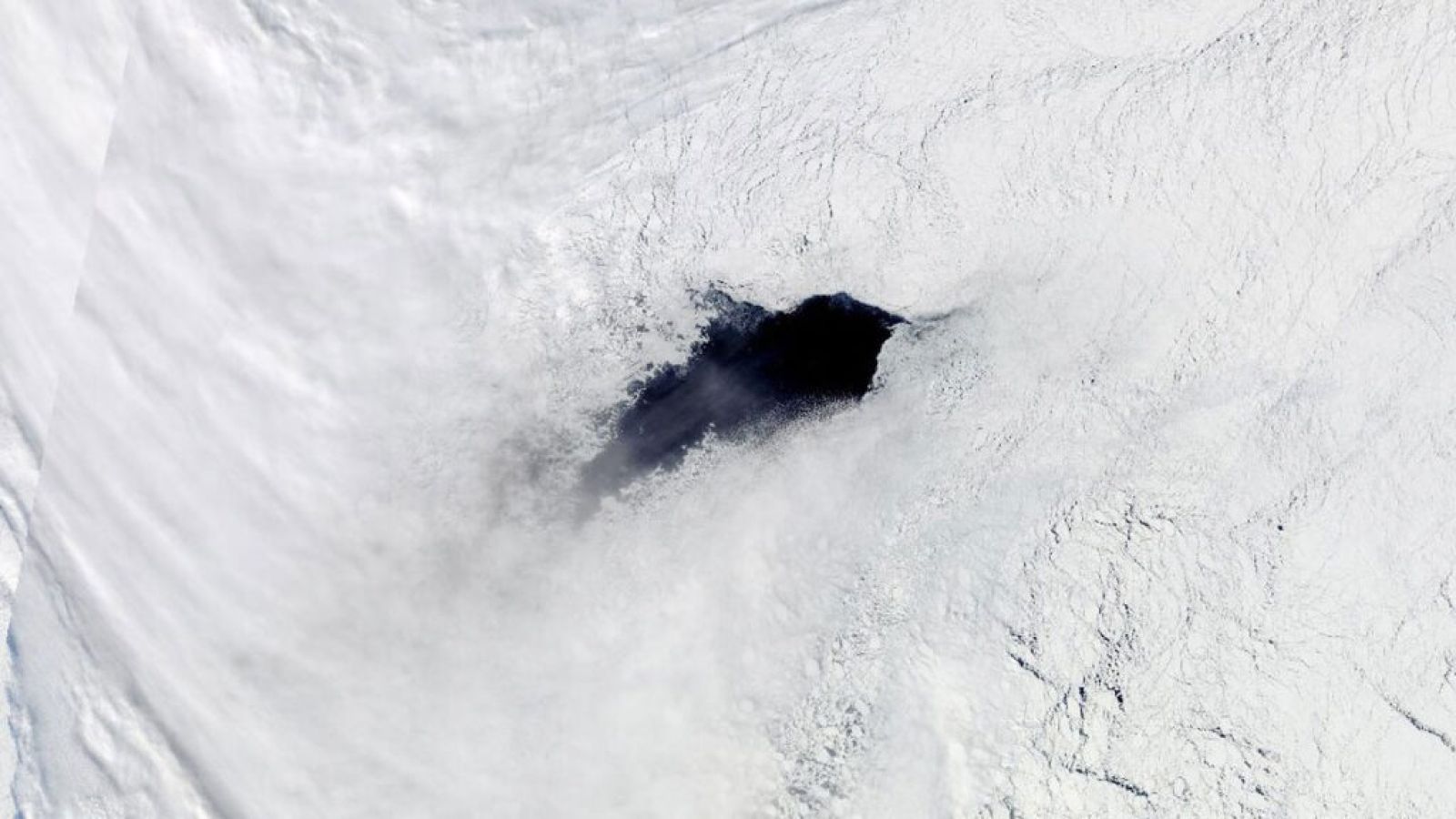

The return of the Maud Rise polynya, a giant hole in the sea ice, illustrates this disruption. Absent since the 1970s, its reappearance signals a lasting upheaval in ocean conditions.

Aerial view of the Maud Rise polynya.

Credit: NASA Earth Observatory

Climate models predicted ice decline, but not this rapidly. Increased salinity creates a feedback loop: less ice exposes more ocean to sunlight, amplifying warming.

Global consequences

Antarctic sea ice plays a key role in reflecting sunlight. Its gradual disappearance could alter ocean currents and global weather patterns, with impacts on polar ecosystems and beyond.

CO₂ absorption by the Southern Ocean may also decrease, reducing its role as a climate buffer. Ice-dependent species, like emperor penguins, are directly threatened by these changes.

Continuous monitoring of this region, though challenging, is essential to understanding the climate system's evolution. Satellites and underwater robots provide crucial data to anticipate future disruptions.