🌡️ Car colors are heating up cities... and not just a little

Follow us on Google News (click on ☆)

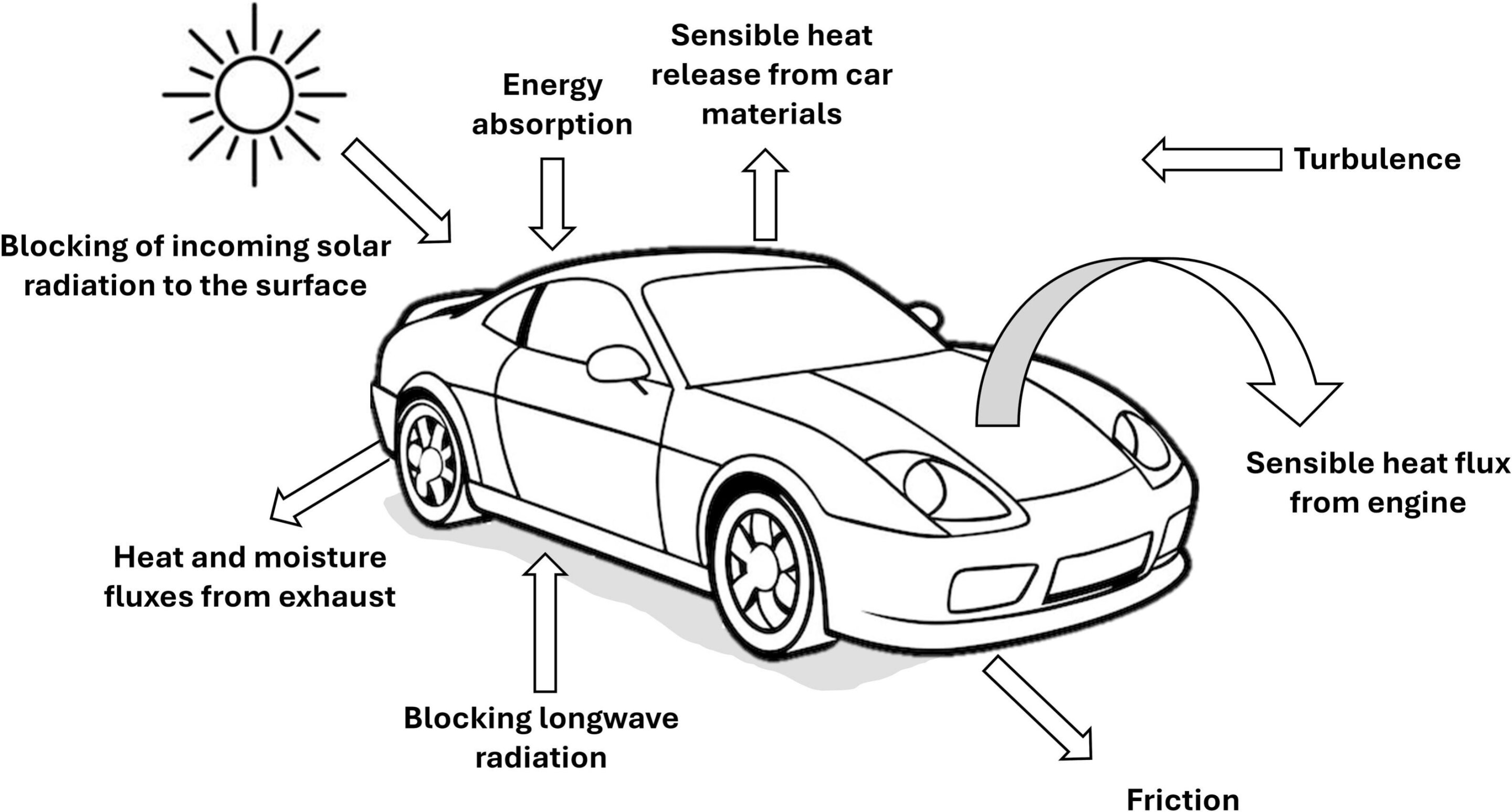

Urban spaces lack vegetation, which naturally cools the air through evapotranspiration, a process where plants release water into the atmosphere. In contrast, buildings and roads absorb and retain solar heat, creating what is called the urban heat island effect. Until now, little attention had been paid to cars, despite their omnipresence in city centers.

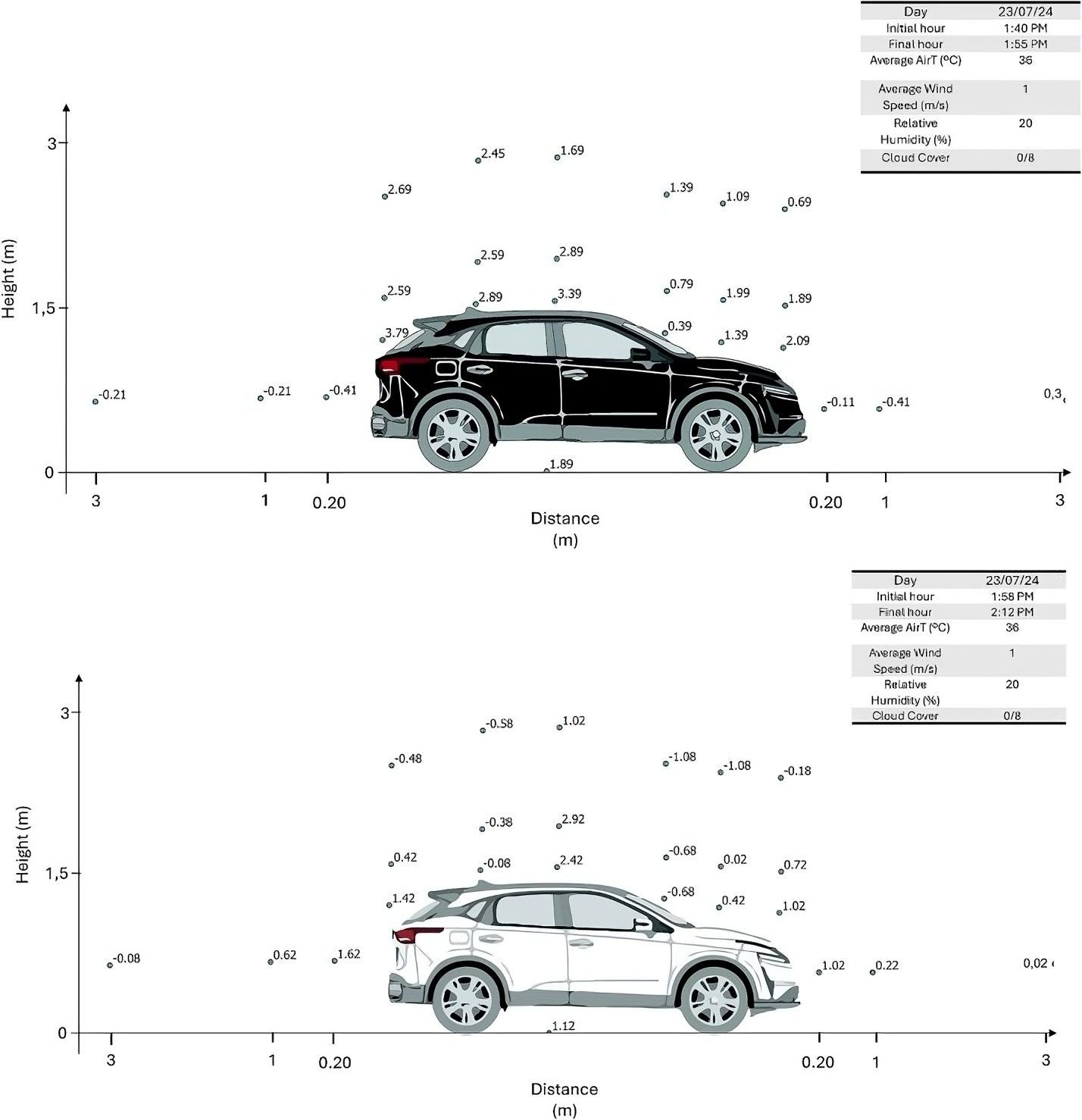

Air temperature differences (ΔT) near a black car and a white car. Both cars were oriented from south to north (from rear to front) and each was isolated and located above an asphalt parking lot. Measurements were taken on July 23, 2024 between 1:40 PM and 2:12 PM. Conditions were calm (average wind speed < 1 ms −1 ) and clear (average received sunlight of 1005 Wm-2).

Credit: City and Environment Interactions (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.cacint.2025.100232

A recent study conducted in Lisbon measured the thermal impact of parked cars. Researchers compared a black car and a white car, left in the sun on an asphalt parking lot. They recorded temperatures at various locations, discovering that the black car increased the air temperature by nearly 4 degrees Celsius (7.2°F) compared to the adjacent asphalt, while the white car had a lesser effect, sometimes even negative.

Vehicle color thus plays a key role, as dark surfaces absorb more sunlight, while light surfaces reflect a large portion of it. White cars can reflect up to 85% of light, thereby reducing their contribution to ambient heat. Additionally, the thin metal layer of car bodies heats up quickly, amplifying this effect in densely populated areas.

By analyzing parking and traffic data, the team estimated that if all cars were white, the overall reflection of light, or albedo, could nearly double in some parts of the city, significantly decreasing solar radiation absorption. This would open the way to urban planning strategies focused on heat reduction, such as the use of reflective coatings or shading structures.

The authors propose practical measures, such as restrictions based on vehicle color in heat-sensitive areas, or incentives for reflective coatings. Combined with other approaches like tree planting or green roofs, these actions could mitigate the heat island effect, improving comfort and health in cities.

Impacts of cars on urban environments, adapted from scientific sources.

Credit: City and Environment Interactions (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.cacint.2025.100232

Albedo and light reflection

Albedo is a measure of a surface's ability to reflect sunlight, ranging from 0 (total absorption) to 1 (total reflection). High-albedo surfaces, like snow or white roofs, reflect a large portion of solar energy, while low-albedo surfaces, like dark asphalt, absorb it, contributing to warming.

In urban environments, albedo directly influences ambient temperature. For example, a white car with an albedo of about 0.8 reflects up to 80% of light, reducing its thermal impact, unlike a black car with an albedo close to 0.1, which absorbs almost all energy and heats its surroundings.

Increasing the overall albedo of cities through reflective materials can significantly decrease the heat island effect. This involves rethinking color choices for vehicles, buildings, and ground coverings to maximize reflection and minimize heat absorption.

This approach is part of passive cooling solutions, complementary to other measures like shading and vegetation, to create cooler and more energy-efficient urban spaces without requiring expensive air conditioning systems.