Discovery of an underwater "Pompeii" in Morocco

Published by Redbran,

Source: The Conversation under Creative Commons license

Other Languages: FR, DE, ES, PT

Source: The Conversation under Creative Commons license

Other Languages: FR, DE, ES, PT

Follow us on Google News (click on ☆)

Volcanoes located at the boundary of tectonic plates are known for their explosive, large-scale eruptions, which can generate several tens of cubic kilometers of material. These eruptions can almost instantly trap the present life, preserving under their ashes the records of entire civilizations, much like Pompeii, buried under the ashes of Vesuvius.

Artist's view of the volcanic explosion that buried the trilobites.

Provided by the author

An international team of researchers, which I coordinated, has just published an article featured on the cover of the leading American journal Science, describing the discovery of two new species of trilobites. These are the best-preserved trilobite fossils ever discovered.

They reveal unprecedented anatomical details despite the millions of trilobites collected and studied over the past two centuries. These fossilized arthropods, found petrified in their final posture, represent a 515-million-year-old (Myr) ecosystem, a "marine Pompeii," discovered in volcanic ash layers in Aït Youb, in the Souss-Massa region of Morocco. This work is highlighted on the cover of Science magazine.

With more than 22,000 species discovered, trilobites are likely the most well-known fossil invertebrates. While their calcite exoskeleton gives them a high fossilization potential (which explains their large numbers), their non-mineralized appendages and internal organs are known only from a limited number of specimens.

Trilobites have been extinct since the end of the Paleozoic era (539-252 million years ago). They were marine arthropods varying in size from one to a few centimeters. The ones we discovered are about 0.8 inches (2 cm). Today, their closest morphological "descendants" are horseshoe crabs. These are also marine arthropods but are distant cousins.

Trilobite molds

At Aït Youb, during a volcanic eruption, living organisms were buried by pyroclastic flows. The intense heat consumed the biological tissues, leaving only cavities in the solidified ash: the molds of the organisms. These preserved the finest details of the trilobites' outer surface, including hairs and spines along the appendages. Their digestive tube was also preserved after filling with ashes. Even small shells (brachiopods) attached to their exoskeleton by a peduncle were frozen in their living position.

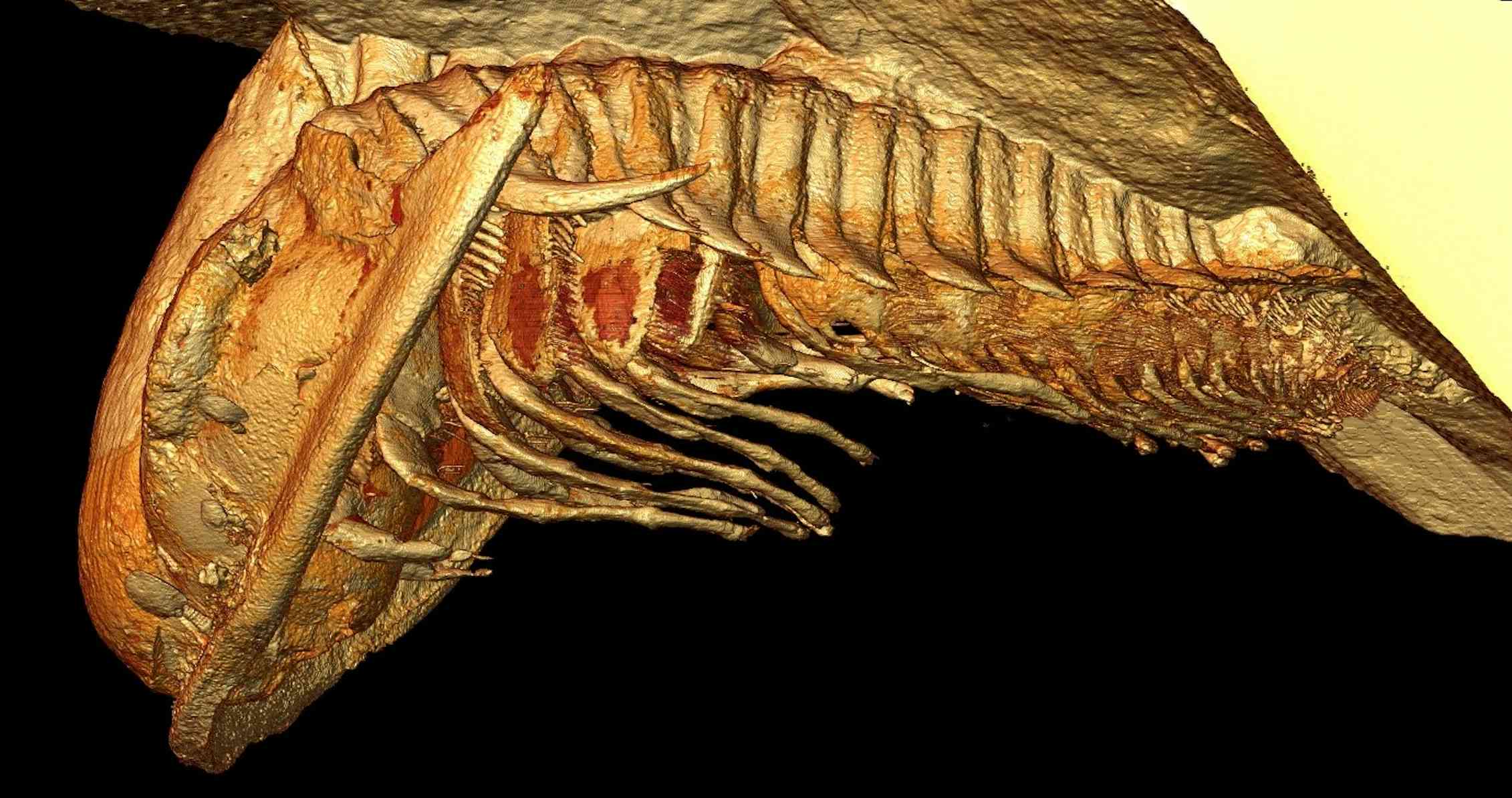

Ventral view of a micro-CT reconstruction of a trilobite Gigoutella mauretanica.

A. Mazurier, Abderrazak El Albani, Provided by the author

Using an imaging technique, X-ray microtomography, we were able to study the fossils in 3D without extracting them from their matrix. This technique relies on the property of X-rays to penetrate matter and be absorbed according to the nature and density of the components they encounter. By digitally filling their mold, the vanished bodies were reconstructed with striking detail.

This work, carried out by Arnaud Mazurier, Research Engineer at the University of Poitiers, provides unprecedented insight into the anatomical organization of trilobites. The results notably revealed in remarkable detail a clustering of specialized leg pairs around the mouth, providing a clearer idea of how they fed. They also reveal, for the first time for these fossils, the presence of a labrum, a fleshy lobe acting as an upper lip in current arthropods.

Lateral view of a micro-CT reconstruction of a trilobite Gigoutella mauretanica.

A. Mazurier, Abderrazak El Albani, Provided by the author

Optimal preservation thanks to volcanic ash

This discovery demonstrates the crucial role of volcanic ash deposits in fossil preservation and the critical importance of exploring volcanic underwater environments.

It also shows that X-ray microtomography is a powerful tool for observing fossilized objects in very hard rocks in 3D, without risking damage. Thus, pyroclastic deposits (rocks composed mostly or exclusively of volcanic material) should become new study targets given their extraordinary potential to trap and preserve biological remains, even soft tissues, without causing degradation. New windows should thus open on our planet's past.

To illustrate the impact of our discovery, Greg Edgecombe, curator at the Natural History Museum in London, specialist in arthropods, and co-author of the study, stated: "I have been studying trilobites for nearly 40 years, but I had never felt like looking at living animals as I did with these. I have seen a lot of soft anatomy of trilobites, but it is the 3D preservation here that is truly astounding."