Follow us on Google News (click on ☆)

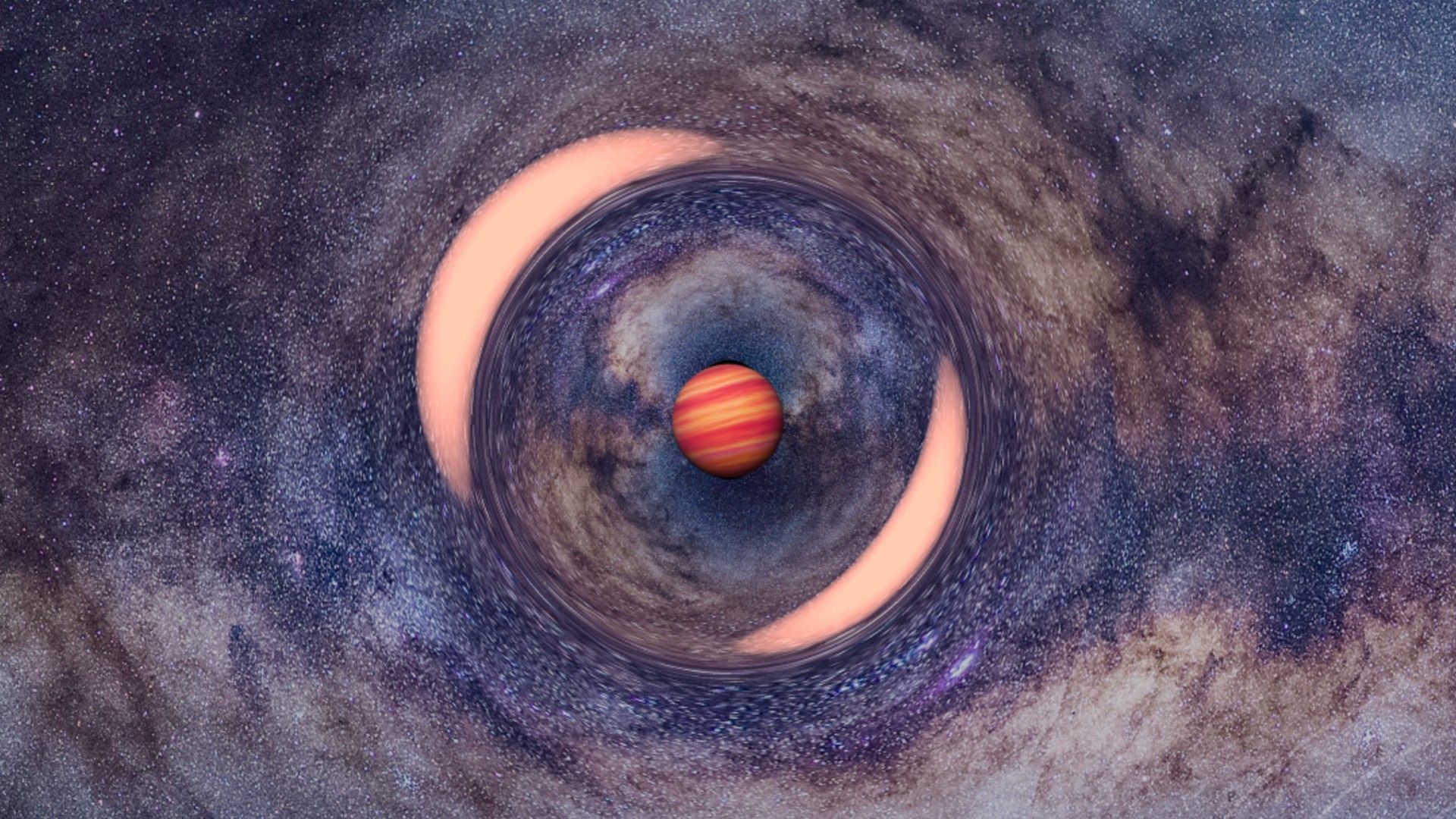

To detect these invisible objects, scientists rely on a natural phenomenon: gravitational microlensing. When a rogue planet passes in front of a distant star, its gravity bends the light from that star, acting as a cosmic magnifying glass. This temporary amplification of brightness allows telescopes to reveal the presence of planets that would otherwise remain hidden in the darkness.

Illustration of a rogue planet creating a gravitational microlensing event on a distant star, with magnified images forming an Einstein ring.

Credit: J. Skowron, K. Ulaczyk / OGLE

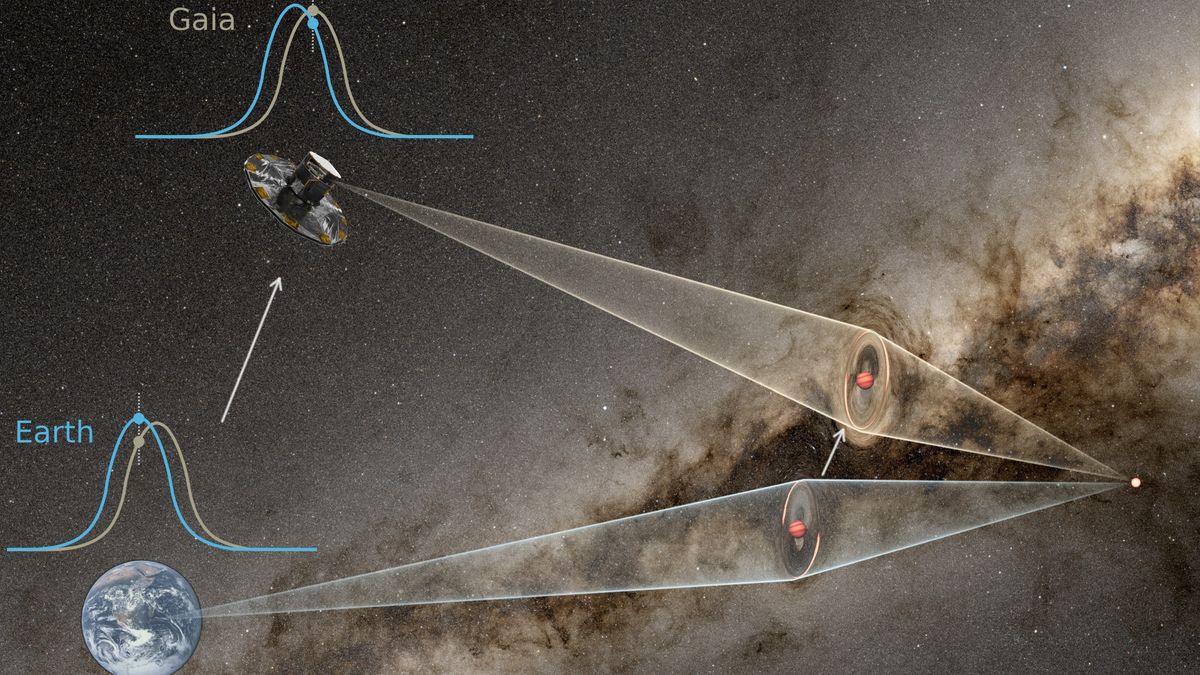

An international team recently observed a microlensing event designated KMT-2024-BLG-0792 and OGLE-2024-BLG-0516. By cross-referencing data from ground-based observatories with that from the European Space Agency's Gaia satellite, the researchers were able to precisely determine the distance and mass of the responsible object. It is a rogue planet located about 9,950 light-years from Earth, towards the center of the Milky Way, with a mass comparable to that of Saturn.

According to current theories, these solitary planets would be extremely numerous in our galaxy. Andrzej Udalski, an astrophysicist at the University of Warsaw, explains in the study published in Science that their number could exceed that of stars. This abundance indicates that planetary formation is a dynamic process, where chaotic interactions can eject worlds from their stellar systems.

Measuring the distance of these planets is fundamental for deducing other characteristics, such as their mass. Until now, gravitational microlensing did not directly provide this information, leaving room for much uncertainty. The new method exploits parallax, by observing the event from different points, which allows for precise triangulation. Thanks to this, astronomers have not only confirmed the planetary nature of the object, but have also ruled out the hypothesis of a brown dwarf.

Artist's impression of a rogue planet deflecting light from a distant source.

Credit: J. Skowron / OGLE

Study prospects look promising with the arrival of new instruments. NASA's Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope, whose launch is scheduled for 2026, will scan vast regions of the sky in infrared light at an accelerated pace. For its part, the Chinese Earth 2.0 satellite, expected to launch around 2028, will contribute to the search for rogue planets. These missions should multiply discoveries and refine our understanding.

This advance broadens our knowledge about the diversity of planets. It demonstrates that starless worlds are not anomalies, but common elements of galactic evolution. By studying these rogue planets, scientists hope to elucidate the mechanisms that govern the birth and fate of planetary systems, far beyond our stellar neighborhood.

Gravitational Microlensing

This phenomenon occurs when a massive object, like a planet, passes between a distant star and an observer on Earth. According to Einstein's theory of general relativity, gravity bends spacetime, deflecting the path of light. Thus, the object acts as a natural lens, temporarily amplifying the brightness of the background star.

Artist's impression of the KMT-2024-BLG-0792/OGLE-2024-BLG-0516 microlensing event, observed from Earth and space.

Credit: J. Skowron / OGLE

For astronomers, gravitational microlensing is a valuable tool because it allows the detection of dark or faint objects that escape traditional methods. Unlike planets orbiting stars, which can be observed by transit or radial velocity, rogue planets do not emit or reflect enough light to be seen directly.

Applying this technique requires constant monitoring of vast areas of the sky, as microlensing events are brief and unpredictable. Projects like OGLE (Optical Gravitational Lensing Experiment) regularly scan the galactic center to capture these fleeting signals.

Despite its advantages, microlensing has limitations, such as the difficulty in determining the object's distance without complementary observations. This is why recent advances, combining ground-based and space data, mark an important step in refining measurements and confirming the nature of rogue planets.

The Origins of Rogue Planets

Several scenarios explain how planets can end up alone in space. One of the most common involves violent gravitational interactions within young planetary systems. During formation, developing planets can collide or be ejected by the influence of other bodies, like gas giants or neighboring stars.

Another possible mechanism is perturbation by passing stars. In dense regions of the galaxy, such as star clusters, the passage of a star can destabilize a planet's orbit, propelling it out of its system. This process helps populate interstellar space with wandering worlds over long periods.

Some rogue planets might also form directly from clouds of gas and dust, never being bound to a star. Similar to brown dwarf stars but with lower mass, these objects are born through gravitational collapse in isolated regions. Their study helps understand the boundary between planets and stars.

The diversity of these origins shows that rogue planets are not a rare product, but a natural consequence of galactic dynamics. By cataloging them, researchers can reconstruct the history of planetary formation and estimate how many similar worlds populate the Milky Way, beyond our current perception.