🦘 Giant kangaroos capable of leaping? A game-changing discovery

Follow us on Google News (click on ☆)

Researchers have focused on the bone architecture of these extinct animals. Their analysis examined nearly 40 fossils of giant kangaroos, including the extinct group Protemnodon, whose hind limbs were compared to those of 94 contemporary specimens. The observation particularly focused on a foot bone playing a major role in jumping: the fourth metatarsal.

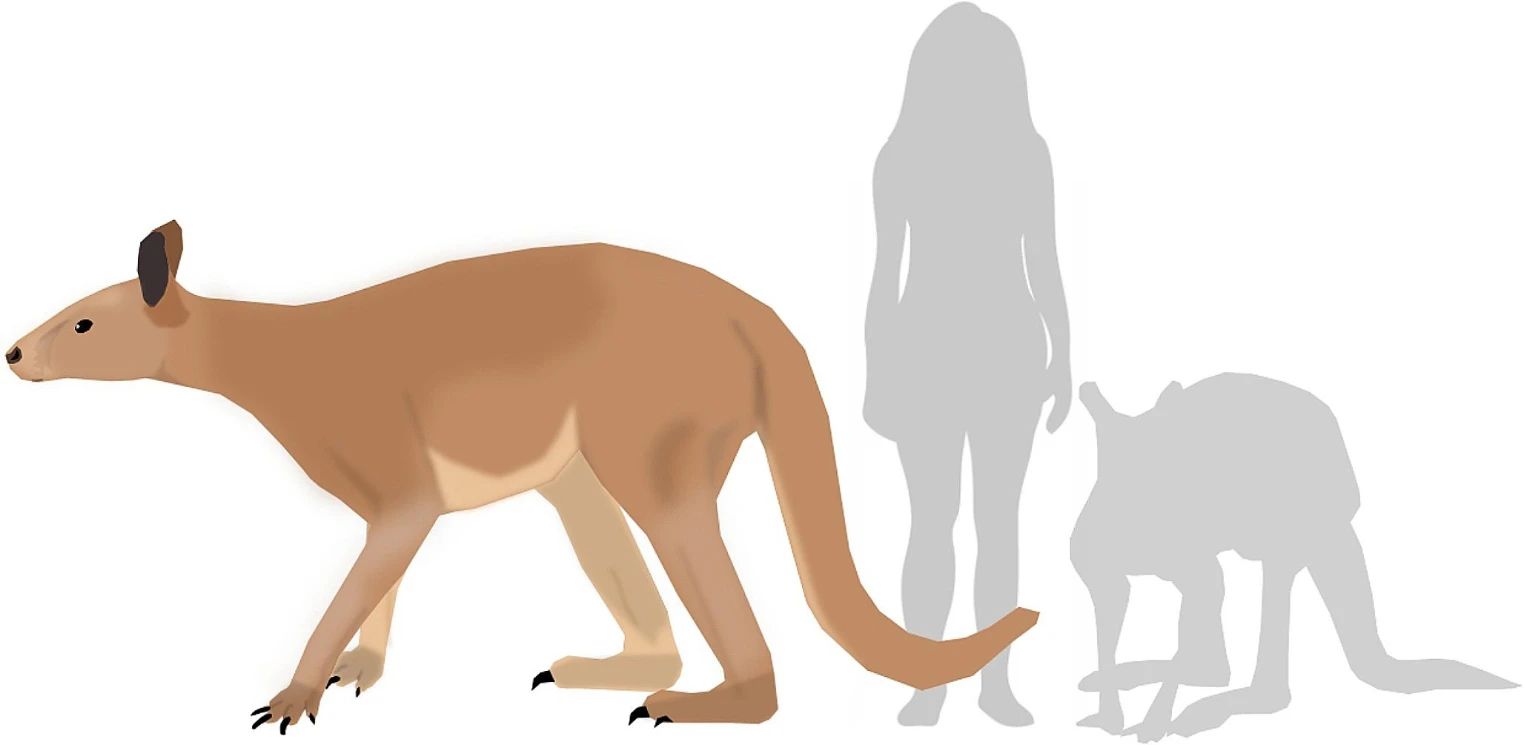

Protemnodon next to a human and the largest living kangaroo, the red kangaroo (Osphranter rufus).

The results, published in Scientific Reports, indicate that these bones showed sufficient robustness. The calculations assessed their resistance to the forces generated during a leap. Contrary to previous assumptions, the metatarsals of all giant species appear to have been capable of withstanding this considerable physical stress.

The team also examined the heel bone and the potential insertion point of the Achilles tendon. They thus estimated the dimension required for a tendon cushioning the impact in animals of such mass. The heels of the fossils appear wide enough to have anchored tendons of this thickness, which supports the hypothesis of an aptitude for leaping.

Sthenurine skeleton at the South Australian Museum.

Credit: Megan Jones

This ability does not mean, however, that these giants covered long distances by leaping. Their imposing mass made this mode of locomotion uneconomical over distance. The authors instead envision brief and intense leaps, used in specific situations.

This faculty could have been an asset for avoiding predators, such as the marsupial lion Thylacoleo. A comparable behavior is observed in some current rodents and small marsupials, which sometimes perform leaps. The locomotion of these extinct animals thus reveals itself to be undoubtedly more diverse than what was assumed.