Humans have observed only 0.001% of the ocean floor 🌊

Published by Cédric,

Article author: Cédric DEPOND

Source: Science Advances

Other Languages: FR, DE, ES, PT

Article author: Cédric DEPOND

Source: Science Advances

Other Languages: FR, DE, ES, PT

Follow us on Google News (click on ☆)

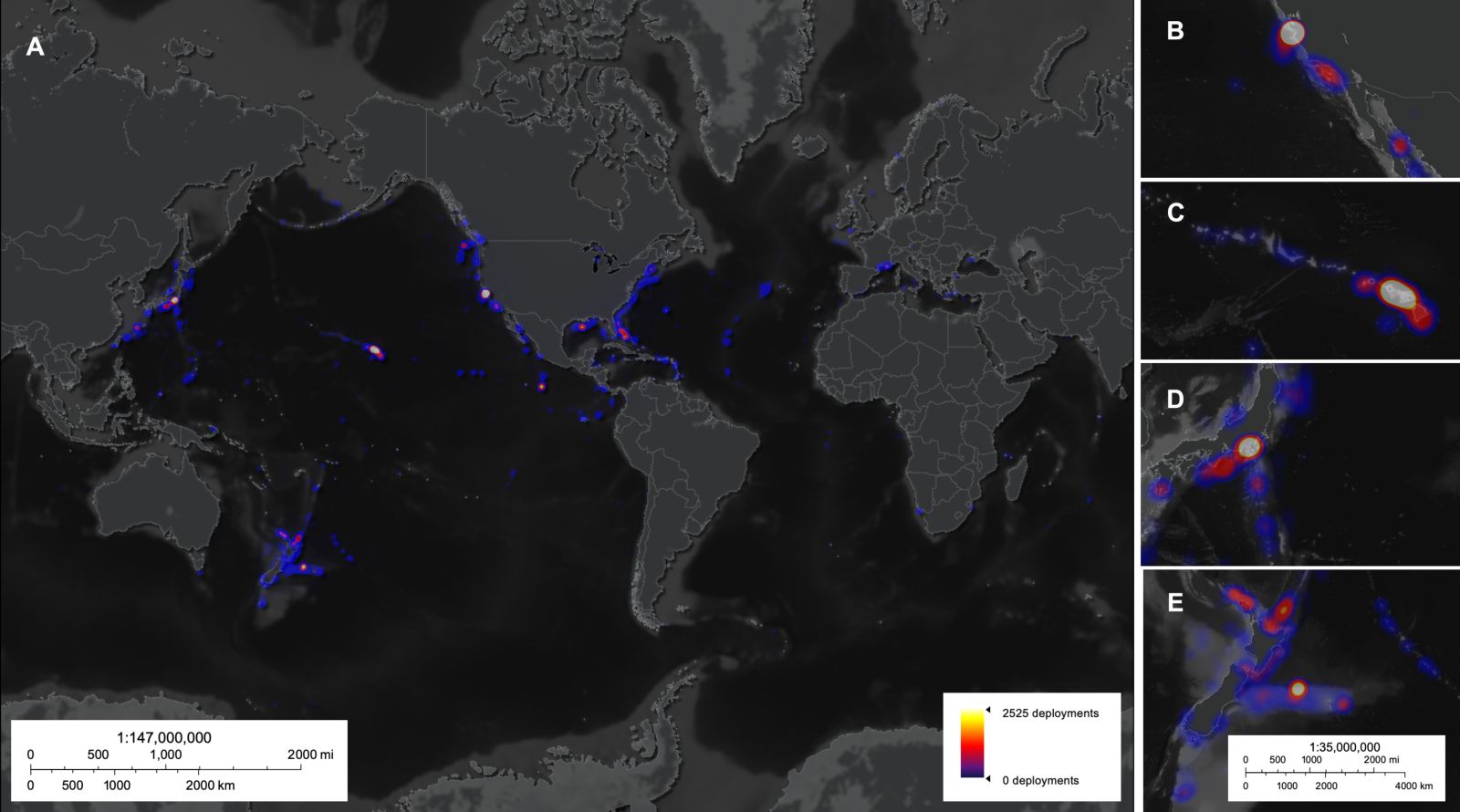

A - Deep-sea diving activity between 1958 and 2024 is concentrated in a few specific areas.

B - High activity in Monterey Bay, United States.

C - Notable activity around Hawaii, United States.

D - Activity concentrated in Suruga and Sagami Bays, Japan.

E - Significant activity off the coast of New Zealand. The map shows the number of dives per 250 km² (96.5 sq mi) area, not the actual explored surface, which is much smaller.

Ocean depths beyond 200 meters (656 feet) host unique ecosystems and poorly understood geological processes. A recent study published in Science Advances highlights that visual explorations remain rare, costly, and concentrated near the coasts of a few wealthy nations.

A glaring geographical imbalance

65% of observations come from the exclusive economic zones of the United States, Japan, and New Zealand. These three nations, along with France and Germany, account for 97% of recorded dives since 1958.

This overrepresentation skews our understanding of the abyss. Conditions observed near California or Japan likely differ from those in the tropical Atlantic or the Southern Ocean.

Historical data, often limited to black-and-white photos, exacerbate this bias. Modern technologies like 4K cameras or laser scanners could transform our perception of deep-sea ecosystems—if deployed on a larger scale.

Technology and cooperation: the keys to exploration

Submarine canyons and hydrothermal vents capture attention, leaving the abyssal plains—though predominant—in the shadows. These neglected zones are nonetheless essential for assessing the impact of warming or deep-sea mining.

The cost of submersibles and research vessels hinders progress. Low-cost robots and autonomous cameras are emerging as solutions for less-equipped countries.

The authors advocate for open sharing of archives and large-scale imaging campaigns. Machine learning and submarine cables could accelerate the discovery of species or new habitats.

Major consequences for the planet

This lack of knowledge about the abyss undermines our ability to protect these vital ecosystems. Without precise data, it's impossible to assess the real impact of deep-sea fishing, mining, or climate change on these environments. Policy decisions, such as authorizing industrial projects in deep waters, thus rely on incomplete models—risking the irreversible destruction of unknown species or ecosystems.

Moreover, the deep ocean regulates the climate and produces part of Earth's oxygen. Ignoring its workings means missing potential solutions to mitigate warming or discover new medical molecules. Bridging these gaps requires a global effort, combining technological innovation and scientific cooperation, before human activity irreversibly alters this last great unexplored frontier.