Ouch! Owie! Ow! - Why do cries of pain sound similar in all languages? 🤔

Published by Adrien,

Source: The Conversation under Creative Commons license

Other Languages: FR, DE, ES, PT

Source: The Conversation under Creative Commons license

Other Languages: FR, DE, ES, PT

Follow us on Google News (click on ☆)

From "ouch" to "aïe", human expressions of pain are strikingly similar worldwide, revealing something fundamental about how humans develop language.

We're all familiar with the words we shout out when we bump our heads or burn our fingers. For French speakers, it's often "aïe."

But what words are used to express pain in other languages? Do these "interjections" of pain share similar sounds across the globe, as one might expect since cries of pain are reflex reactions?

We've just published an article in the scientific magazine Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, delving into this question for the first time.

For this study, we cataloged vowels (a, i, o, etc.) found in pain, disgust, and joy interjections across more than 130 languages worldwide. We then compared them to the vowels used in non-linguistic vocalizations (screams, groans, etc.) to determine if interjections and vocalizations share common sounds.

Our findings reveal that pain interjections indeed resemble non-linguistic vocalizations. However, this observation does not clearly apply to expressions of disgust or joy.

What is an interjection?

An interjection is a word that can stand alone (like "ouch!" or "wow!"). Interjections do not combine grammatically with other words in a sentence.

Since linguists mainly focus on grammatical structures, they haven't traditionally paid much attention to interjections. As a result, some very basic questions about interjections remain unanswered—despite their frequent presence in spoken language and their fundamental role in communication.

Pain, disgust, and joy

The primary goal of our research was to determine if certain vowels are more commonly used in interjections depending on the emotion or effect they express.

If so, we also wanted to investigate whether these patterns could be linked to the acoustic properties of non-linguistic vocalizations like cries or groans.

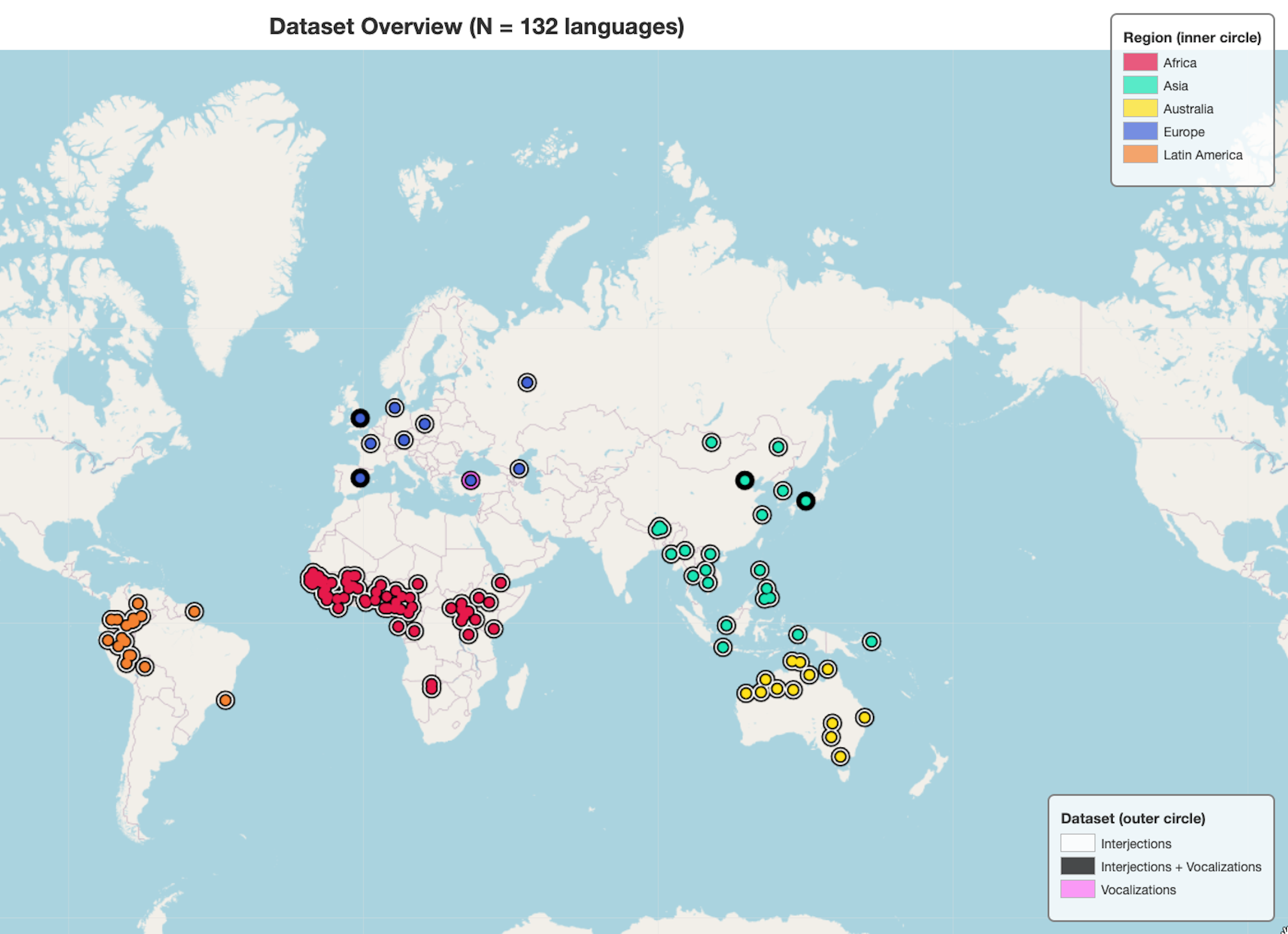

To answer these questions, we collected interjections for pain, disgust, and joy from dictionaries of 131 languages across Africa, Asia, Australia, and Europe, totaling more than 500 interjections.

Map of languages for which we collected interjections (131) and vocalizations (5). Only one language—Turkish—had vocalizations but no interjections.

Ponsonnet et al. (2024)

To compare interjections to other words in these languages, we relied on databases containing word lists from our language sample. This enabled us to apply statistical tests to compare the vowel distribution in interjections versus other words.

These tests show that, on average, the pain interjections in our sample contain more "a" sounds and more vowel sequences like "ay" (as in "aïe") and "aou" (as in "ouch"). This observation holds true across all world regions for which we collected data.

It's important to note that this doesn't mean all pain interjections necessarily contain "a," "ay," or "aou." However, a randomly selected pain interjection is more likely to include one of these sounds compared to a disgust or joy interjection, or any random word.

Of the three types of emotional expression we examined, this property only applies to pain. The vowels in disgust and joy interjections are not distinct from the vowels in other words.

This shows that the vowels in pain interjections aren't randomly chosen—prompting the question: where do they come from?

Pain interjections resemble pain vocalizations

To explore this question, we analyzed the sounds people make when expressing pain, disgust, or joy.

We asked speakers of English, Japanese, Chinese (Mandarin), Spanish, and Turkish to produce sounds for these emotional experiences without using conventional words. Then, we analyzed the vowels used in these vocalizations.

We found that the type of vowels used is specific to each emotion: more "a" for pain, more "neutral" vowels (like the first vowel in "petit") for disgust, and more "i" for joy.

In other words, interjections and non-linguistic vocalizations for pain both have more "a." However, disgust and joy interjections do not use the same vowels as their corresponding vocalizations.

What can we conclude?

Our study shows that the sounds of interjections, although conventional and specific to each language, are not entirely arbitrary. Pain interjections contain more "a," "ay," and "aou," and the "a" aligns with vowels found in non-linguistic vocalizations.

This suggests that pain interjections may partly derive from the (non-linguistic) sounds we produce when experiencing pain. In contrast, this does not seem to be the case for disgust or joy interjections.

These findings could shed light on broader questions about the origins of language and linguistic forms. Words are often seen as arbitrary combinations of sounds: for instance, the word “house” in English versus “casa” in Spanish is generally considered purely conventional. However, certain aspects of language may be less arbitrary than others.

Pain—a critical dimension of human experience—elicits strong physiological and emotional reactions, possibly to the point of influencing the shape of certain words used to express it.

Many questions remain unanswered. In this study, we focused on vowels. This raises the question: what about consonants (p, t, s, etc.)? And what about other emotions beyond pain, disgust, and joy?

Future research on these topics could help us evaluate the embodied nature of human language and better understand how language originally emerged.