Follow us on Google News (click on ☆)

A recent study published in Communications Psychology shows that our confidence in our judgments about the veracity of information does not predict the accuracy of these judgments. Yet this confidence is the main factor motivating the demand for additional information to reduce uncertainty about ambiguous information.

A revealing experiment

In this experiment, 259 participants had to assess the veracity of brief, emotionally neutral information related to topics of ecology, democracy, and social justice. These articles, deliberately ambiguous, could be true or false.

After giving their opinion, participants had to indicate their level of confidence and decide whether they wanted to consult additional information to verify their judgments. For this, they were asked to indicate how much they were willing to pay to access this additional information (debunking) through a procedure ensuring a reliable revelation of their preferences.

The results are striking: participants' confidence in their ability to distinguish truth from falsehood often had little to do with their actual ability to judge the veracity of the information. A high level of confidence, even when judgments were incorrect, reduced the likelihood of seeking additional information.

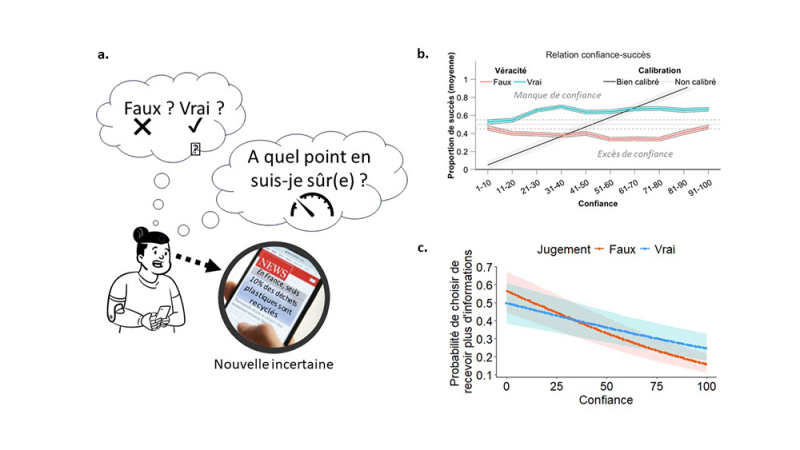

a - Participants read a brief news item and had to estimate the probability of it being true or false, allowing for the measurement of both their judgment of veracity and their confidence in their judgment.

b - Participants' confidence in their judgment of veracity was uncalibrated, meaning it was dissociated from their ability to discern true information from false information.

c - Despite this dissociation, it was based on their confidence in their judgment that participants decided when to receive more information.

© Jean-Claude Dreher

Conversely, less confident participants - even when their judgments were accurate - were more inclined to dig deeper into the truth by seeking more information. This discrepancy creates a critical problem: unawareness of their own shortcomings prevents individuals from correcting their mistakes.

The impact of information ambiguity

The characteristics of the information also play an important role. Imprecise or highly polarizing but true information is often, wrongly, considered false with a high degree of confidence. On the other hand, false information that appears precise or less polarizing is often considered true.

The ambiguity of the information, more than personal convictions or cognitive biases, emerged as the main culprit, leading participants to judgment errors and preventing them from correcting their misperception by seeking corrective information.

A challenge to combat misinformation

This study highlights a dual problem. On one hand, ambiguous content pushes us to make judgment errors. On the other hand, misplaced confidence in our ability to assess the truth often prevents us from correcting these errors.

Scientists suggest that to better navigate the ocean of information on social media, we need to learn to better assess our own confidence. Solutions such as debunking education programs or tools to better analyze information could help us improve our decisions when faced with ambiguous content.