🔬 Rabies virus: how can such a minimal virus dominate a human cell?

Follow us on Google News (click on ☆)

A team of Australian researchers has identified the key mechanism used by the rabies virus. Their work, published in Nature Communications, shows that one of its proteins, called P, plays a central role. This protein is capable of performing a multitude of different tasks to take control of the host cell, thus offering an explanation for the virus's formidable efficiency despite its minimal genome.

The key to this versatility lies in the P protein's ability to change its shape and bind to RNA. RNA is a fundamental molecule in our cells, responsible for transporting genetic information and regulating many activities. By interacting with it, the viral protein can access different cellular compartments and orchestrate essential processes there, such as protein production or the immune response.

This strategy may not be exclusive to the rabies virus. Scientists believe other highly dangerous pathogens, such as Nipah and Ebola viruses, could employ a similar approach. If this hypothesis is confirmed, it would pave the way for the development of innovative treatments aimed at blocking this common mechanism, potentially effective against several viral diseases.

The discoveries of this study challenge the traditional model of multifunctional proteins. Previously, they were imagined as trains where each wagon had a specific function. Now, it appears that their capabilities also emerge from the way their parts interact and fold to create different overall shapes, a flexibility that allows them to acquire new properties like RNA binding.

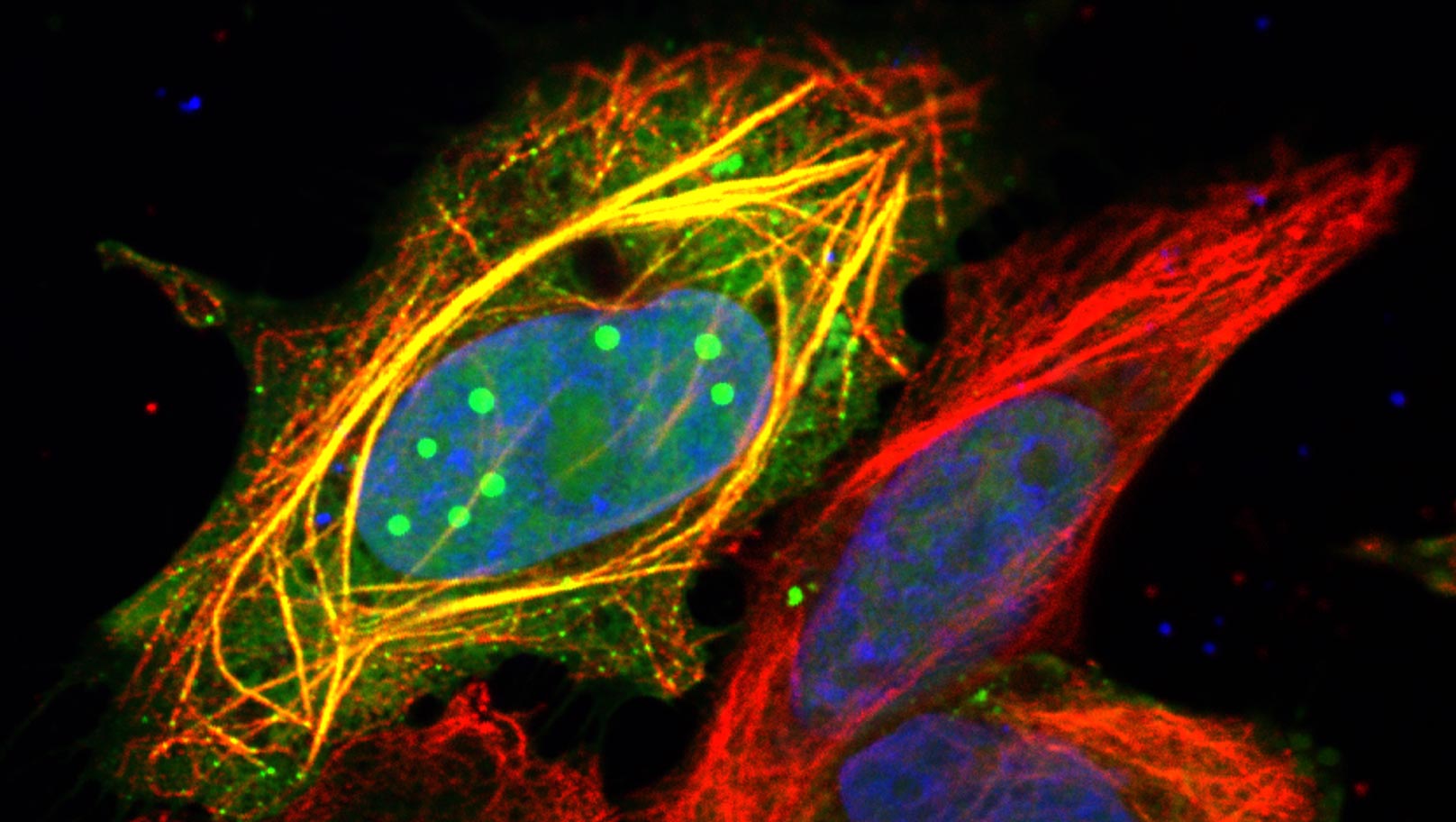

This structural flexibility constitutes the virus's ultimate weapon. By changing shape and binding to RNA, the P protein can navigate between different physical phases within the cell, infiltrating liquid areas that control key functions (see explanation at the end of the article). This adaptation allows it to transform the cell into a highly productive virus factory, while neutralizing its defenses.

Confocal microscopy image of human cells showing the rabies virus P3 protein (in green) forming droplets inside the nucleus (blue) and binding to the microtubule network (red).

Credit: Stephen Rawlinson, Monash University

Understanding this new mechanism offers promising prospects for the design of antivirals or vaccines. By targeting the viral protein's ability to change shape or interact with RNA, it would be possible to disrupt its functioning and prevent infection. This breakthrough, the result of a collaboration between several Australian institutions, could thus durably change our approach to combating some of the most formidable viral infections.

Organization into liquid phases inside cells

Cells are not homogeneous bags but contain many specialized compartments, some of which behave like liquids. These biomolecular condensates, or membrane-less organelles, form through a process called liquid-liquid phase separation. Specific molecules, like proteins and RNA, concentrate there to create micro-environments where important biological reactions take place.

These liquid droplets regulate essential activities, such as protein fabrication in ribosomes, RNA processing in the nucleolus, or the cellular stress response. Their formation and dissolution are dynamic, allowing the cell to adapt quickly to changes. This organization improves the efficiency of processes by bringing necessary molecular actors closer together.

Viruses have evolved to exploit this cellular architecture. By binding to RNA and changing shape, viral proteins like the rabies P protein can enter these liquid compartments. Once inside, they hijack their functions for viral replication, for example by disrupting cellular protein production or evading defense mechanisms.

Studying these interactions opens a research field to understand not only infections but also certain diseases where phase separation is deregulated, as in some neurological disorders. By targeting the ability of viruses to infiltrate these zones, we could develop drugs that protect the integrity of cellular compartments and limit the spread of pathogens.