💀 This mummified conical head reveals a disturbing story

Published by Adrien,

Source: International Journal of Osteoarchaeology

Other Languages: FR, DE, ES, PT

Source: International Journal of Osteoarchaeology

Other Languages: FR, DE, ES, PT

Follow us on Google News (click on ☆)

They determined it was an adult male who died at least 350 years ago, belonging to the Aymara culture rather than Inca. During his childhood, he underwent cranial deformation, a common practice in pre-Columbian South America involving tightly binding infants' skulls to create a conical shape.

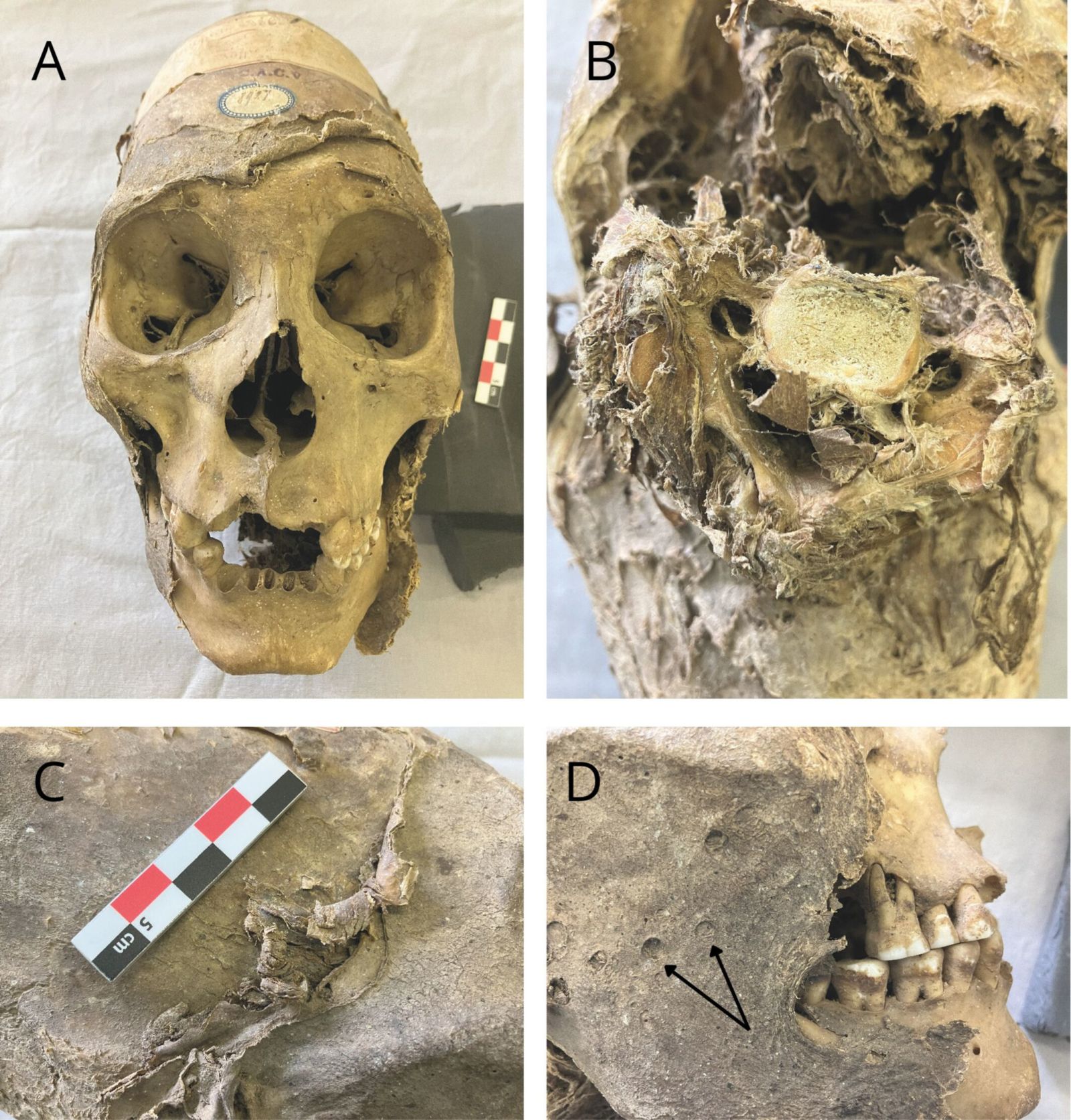

The Bolivian mummified head, with its distinctive conical shape and visible cranial incisions.

Credit: Abegg et al. 2025, Int. J. Osteoarchaeol.; CC BY 4.0

On the top of the skull, deep incisions indicate an attempt at trepanation, an ancient surgical procedure aimed at drilling through the cranial bone. Unlike many cases where this operation was performed in response to trauma, here no injury is apparent, suggesting a ritual or social purpose. The trepanation was not completed, for unknown reasons, possibly due to voluntary interruption or sudden death.

The head's origin was traced through archival notes: it was collected in the 1870s in Bolivia by a Swiss collector, then donated to the museum in 1914. It likely came from a chullpa, a typical stone funerary tower from the Bolivian Highlands region, where the cold, dry climate allowed for natural mummification. This discovery highlights the importance of placing human remains in their cultural and historical context.

Respectful analysis methods, such as non-destructive imaging, were prioritized to honor the dignity of the deceased, avoiding invasive sampling. The researchers, including Claudine Abegg and Claire Brizon, authors of the study published in the International Journal of Osteoarchaeology, emphasize the need to consult local communities for any future research, particularly DNA or isotopic testing that could provide more precise information.

Taphonomic analysis of a mummified skull: views of the face, neck, and cheek. The skin shows natural or intentional tears, curling where it contacts the bone, and marks suggesting insect damage.

This study opens perspectives on the medical and ritual practices of pre-Columbian cultures, showing how trepanation and cranial deformation could intersect. Although the head is not publicly displayed, it remains in the museum's collections, pending possible repatriation requests from Aymara descendants.

Intentional cranial deformation

Cranial deformation was a widespread cultural practice in various ancient societies, particularly in pre-Columbian South America. It involved applying constant pressure to infants' skulls using bandages or boards, modifying their growth to achieve an elongated or conical shape.

This custom was often associated with religious or social beliefs, serving to distinguish members of certain classes or ethnic groups. Deformed skulls were perceived as a sign of beauty, high status, or connection with the divine, and could vary in intensity depending on the region.

Contrary to popular belief, this practice generally did not cause significant brain damage, as the brain possesses plasticity that allows it to adapt to the skull's shape during childhood. Modern studies on ancient skeletons show that individuals who underwent cranial deformation often lived into adulthood without apparent disabilities.

Today, analysis of these skulls helps archaeologists understand migrations and cultural interactions in the past by identifying deformation styles specific to each group.

Trepanation in antiquity

Trepanation is one of the oldest known surgical interventions, practiced since the Neolithic period in various cultures worldwide. It involved drilling or scraping the skull bone to create an opening, often using stone or metal tools.

The reasons for this practice were multiple: treating head trauma, relieving headaches or intracranial pressure, or performing spiritual rituals aimed at driving out evil spirits or facilitating communication with the supernatural. In some cases, it was performed on healthy individuals in a ceremonial context.

Techniques varied considerably, ranging from simple incisions to complete perforations, and the survival rate was surprisingly high, as evidenced by signs of bone healing observed on many ancient skulls. This suggests a certain expertise among practitioners of the time, who had to master anatomy and avoid critical blood vessels.