Follow us on Google News (click on ☆)

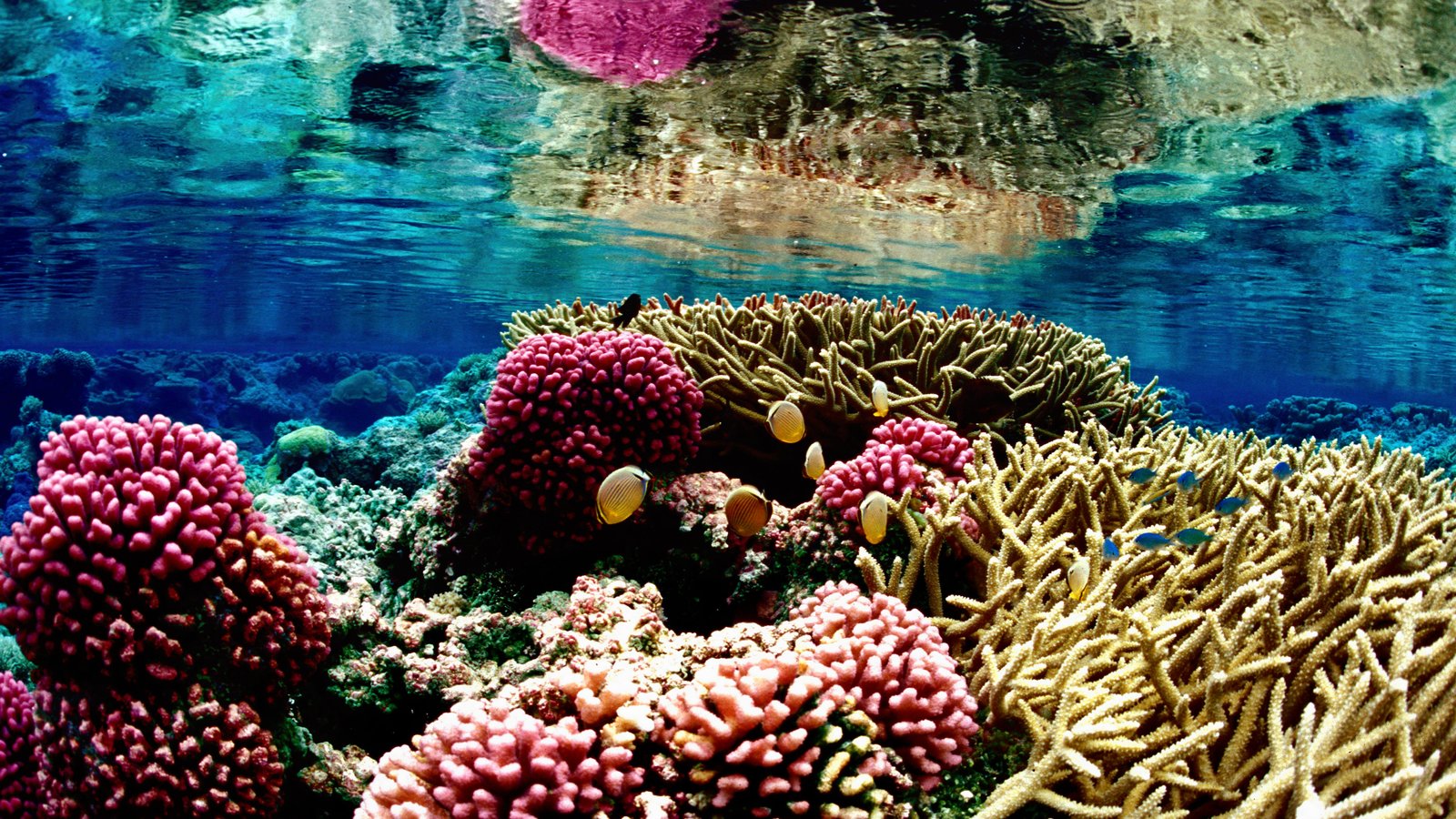

True pillars of marine biodiversity, coral reefs are particularly vulnerable to ocean warming and acidification. Their calcification (formation of the calcium carbonate skeleton), essential to the formation of reef structures, is in rapid decline.

When they calcify, corals secrete carbonates and release CO₂ into the seawater, which slightly reduces the ocean's capacity to absorb CO₂.

If this trend continues, their net dissolution could occur even under moderate emission scenarios. Despite their ecological importance, these ecosystems are not represented in current climate models of the carbon cycle.

The authors used recent estimates on the sensitivity of coral calcification to climate change. They were thus able to deduce the modifications in seawater chemistry resulting from the anticipated decline in global reef calcification. Then, using an ocean biogeochemical model, they simulated the impact of these chemical changes on carbon uptake by the ocean under different emission scenarios, while accounting for the uncertainty in historical calcification rates.

A double-edged mechanism for the planet

According to the study, this future decline in coral calcification could increase the ocean carbon sink by up to 1.25 gigatonnes of CO₂ per year by 2050. This would represent a 5% increase in the cumulative carbon absorption by the ocean during the 21st century compared to current estimates.

The increase in ocean carbon uptake linked to the decline in coral calcification constitutes a negative climate feedback, a concept that current climate models do not take into account. This could lead to an upward revision of the remaining carbon budget, particularly in the context of the +2°C target set by the Paris Agreement.

But this potential "beneficial" effect on the climate cannot compensate for the loss of essential ecosystems. "Even though this work shows that the degradation of coral reefs can have some beneficial effects on the climate, we must not forget that it comes at an enormous cost in terms of biodiversity, coastal protection, and fishing. Environmental policy decisions clearly need to take much more into account than just the carbon aspect," recalls Alban Planchat, co-lead author. A warning to be considered in any environmental policy.