🦴 Discovery of a "Sword Dragon" from the Jurassic period

Follow us on Google News (click on ☆)

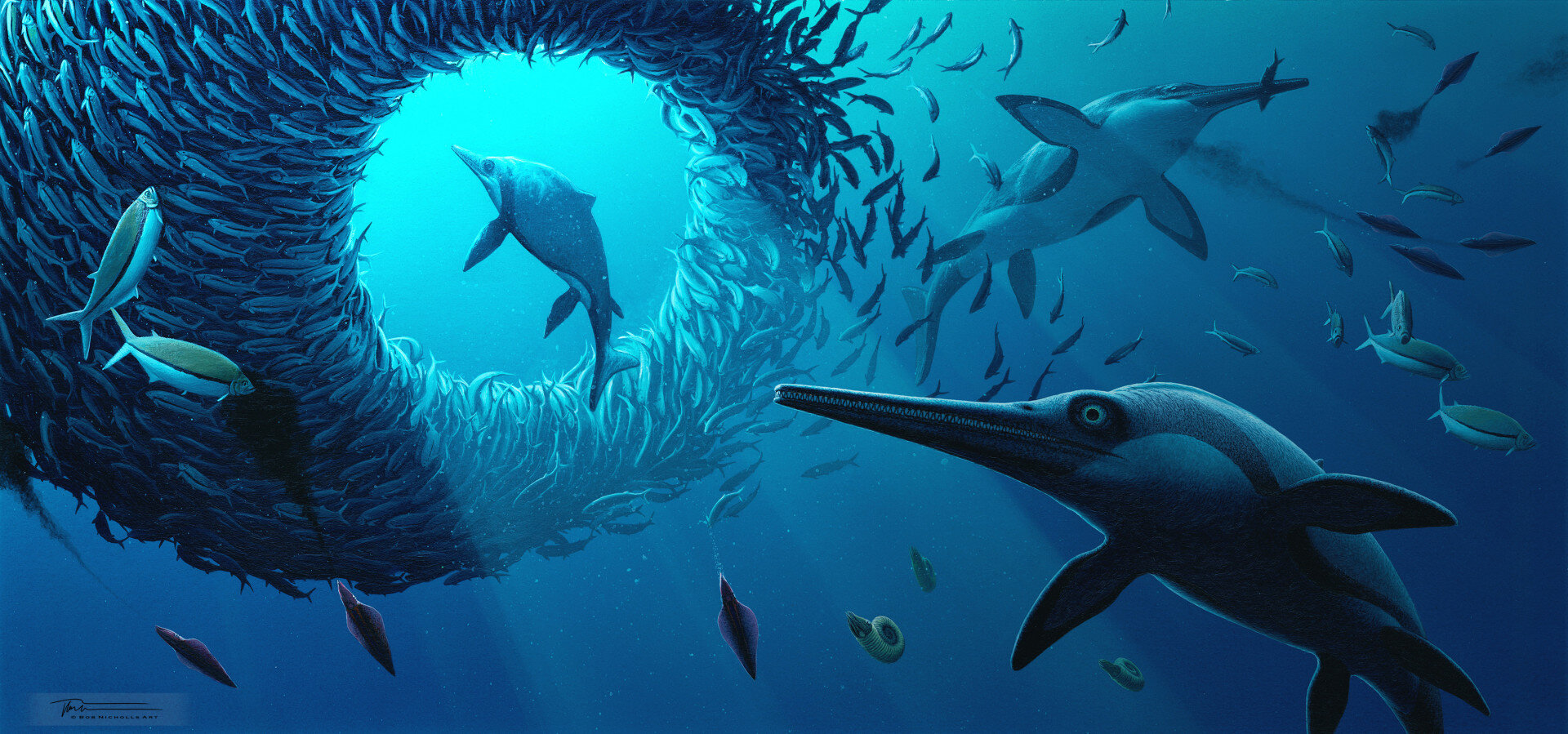

Representation of Xiphodracon goldencapensis, a recently identified ichthyosaur

Credit: University of Manchester

The study of this fossil, conducted by an international team led by ichthyosaur specialist Dr. Dean Lomax, reveals its importance for understanding a significant evolutionary transition. Xiphodracon belongs to the Pliensbachian period, approximately 193 to 184 million years ago, a time when several families of ichthyosaurs disappeared while new ones emerged. Its morphology aligns more closely with species from the late Early Jurassic, indicating that this faunal renewal occurred earlier than previously thought.

Analysis of the bones and teeth shows deformities suggesting the animal survived serious injuries or illnesses, while marks on the skull indicate a bite from a predator, likely another, larger ichthyosaur. These elements offer insight into living conditions in the Mesozoic oceans, where competition and predation were intense. The discovery thus fills a significant gap in the fossil record from this period.

Among the unprecedented anatomical features is a lacrimal bone around the nostril, equipped with fork-shaped bony structures never observed in other ichthyosaurs. The name Xiphodracon, inspired by Greek for "sword" and "dragon," pays tribute to the animal's distinctive appearance and the tradition that designates these marine reptiles as "sea dragons." This fossil, initially discovered in 2001 and acquired by the Royal Ontario Museum, will be displayed to the public, offering a unique opportunity to admire this significant link in evolution.

Detail of the Xiphodracon skull showing its characteristic snout

Credit: University of Manchester

Ichthyosaurs: Masters of the prehistoric oceans

Ichthyosaurs were marine reptiles that dominated the oceans for nearly 160 million years, from the Triassic to the Cretaceous. Their hydrodynamic bodies, similar to those of modern dolphins, allowed them to swim rapidly to hunt prey such as fish and cephalopods.

Unlike dinosaurs, ichthyosaurs were fully adapted to marine life, with fins instead of legs and the ability to give birth to live young, as evidenced by some fossils. Their large eyes, among the largest in the animal kingdom, show that they hunted in deep or dimly lit waters.

The diversity of ichthyosaurs fluctuated throughout geological eras, with peaks of expansion and mass extinctions linked to climatic and environmental changes. Their study helps scientists reconstruct the evolutionary history of marine ecosystems and understand how species respond to biological crises.

The Pliensbachian: A little-known pivotal period

The Pliensbachian is a subdivision of the Early Jurassic, extending from approximately 193 to 184 million years before our era. This period is marked by climatic fluctuations, with episodes of warming and cooling that influenced marine and terrestrial life.

Geologically, the Pliensbachian corresponds to sedimentary deposits rich in fossils, such as those of the British Jurassic Coast, which preserve organisms ranging from ammonites to marine reptiles. These rock layers offer a window into the ecosystems of the time, but they are often undersampled due to their limited accessibility.

Faunal changes during the Pliensbachian, such as the extinction of certain ichthyosaur groups and the emergence of new ones, present rapid evolutionary dynamics. Researchers use fossils like Xiphodracon to date these transitions and explore possible causes, such as variations in sea level or interspecific competition.