Follow us on Google News (click on ☆)

Some treatments use medications capable of stimulating the immune system to enhance its ability to fight cancer/tumor cells: this is called immunotherapy. This approach aims either to amplify the immune response or to help the body better detect and then eliminate cancer cells.

Immunotherapy treatments are effective in responsive patients, but 50 to 80% of patients do not respond to them and the generalized activation of the immune system can cause significant side effects. Finding other solutions to activate our natural defenses is therefore a major challenge in oncology research.

In a new study, a team led by Fabrice Lejeune, Inserm research director at the laboratory for Cancer Heterogeneity, Plasticity and Therapy Resistance (Inserm/CNRS/University of Lille/Lille University Hospital/Pasteur Institute of Lille) has identified an original way to achieve this.

During cell division, mutations can occur within cells. Cancer cells, due to their rapid division, accumulate many more mutations than healthy cells. In theory, these mutations should give rise to defective proteins whose presence should strongly stimulate the immune system, prompting it to destroy cells carrying these proteins. However, whether the cell is cancerous or not, a quality control mechanism prevents defective proteins from being synthesized from mutations.

This mechanism, intended to be protective, is paradoxically problematic in the case of cancer: it allows cancer cells to continue their proliferation while flying under the radar of the immune system.

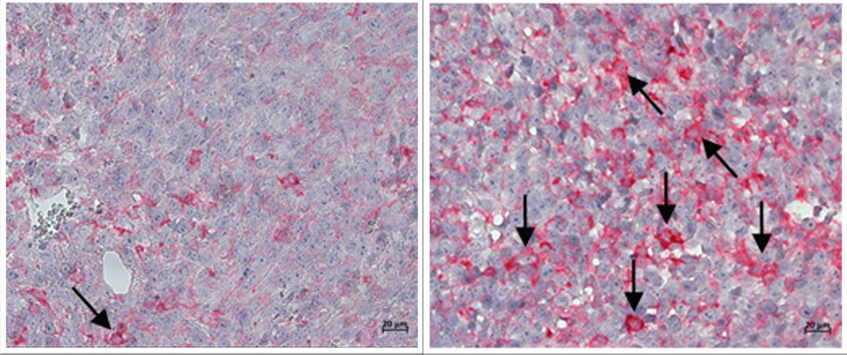

Detection of macrophages (in red and indicated by black arrows) in tumors of untreated mice (left) and DAP-treated mice (right).

© Carmen Sandoval Pacheco and Fabrice Lejeune/Inserm

The researchers have shown that it is possible to bypass this obstacle using a molecule called 2,6-diaminopurine (DAP) in a mouse cancer model. Already known for its ability to reactivate protein production in the presence of a specific type of mutation, DAP here enabled the production of mutant proteins specific to cancer cells.

These proteins display a particular "signature" that does not exist in normal cells and that makes them detectable by the immune system.

When presented to the immune system, this signature triggers a targeted immune response: cancer cells become visible and can be destroyed. In mice, this experimental treatment slowed tumor growth and attracted immune cells to the heart of the tumor.

"These results represent an important step toward new anticancer immunotherapy strategies. Additional work will be needed to evaluate the effectiveness and safety of this approach in humans", explains Fabrice Lejeune, the study's last author.