💥 Scientists are struggling to explain this very strange cosmic explosion

Follow us on Google News (click on ☆)

On one hand, supernovas mark the spectacular end of the most massive stars, scattering elements like carbon or iron into space. On the other, and far less frequent, kilonovas occur when two neutron stars collide. These remnants of dead stars, of extreme density, then merge and generate even heavier elements, such as gold or uranium, which subsequently enrich the cosmos.

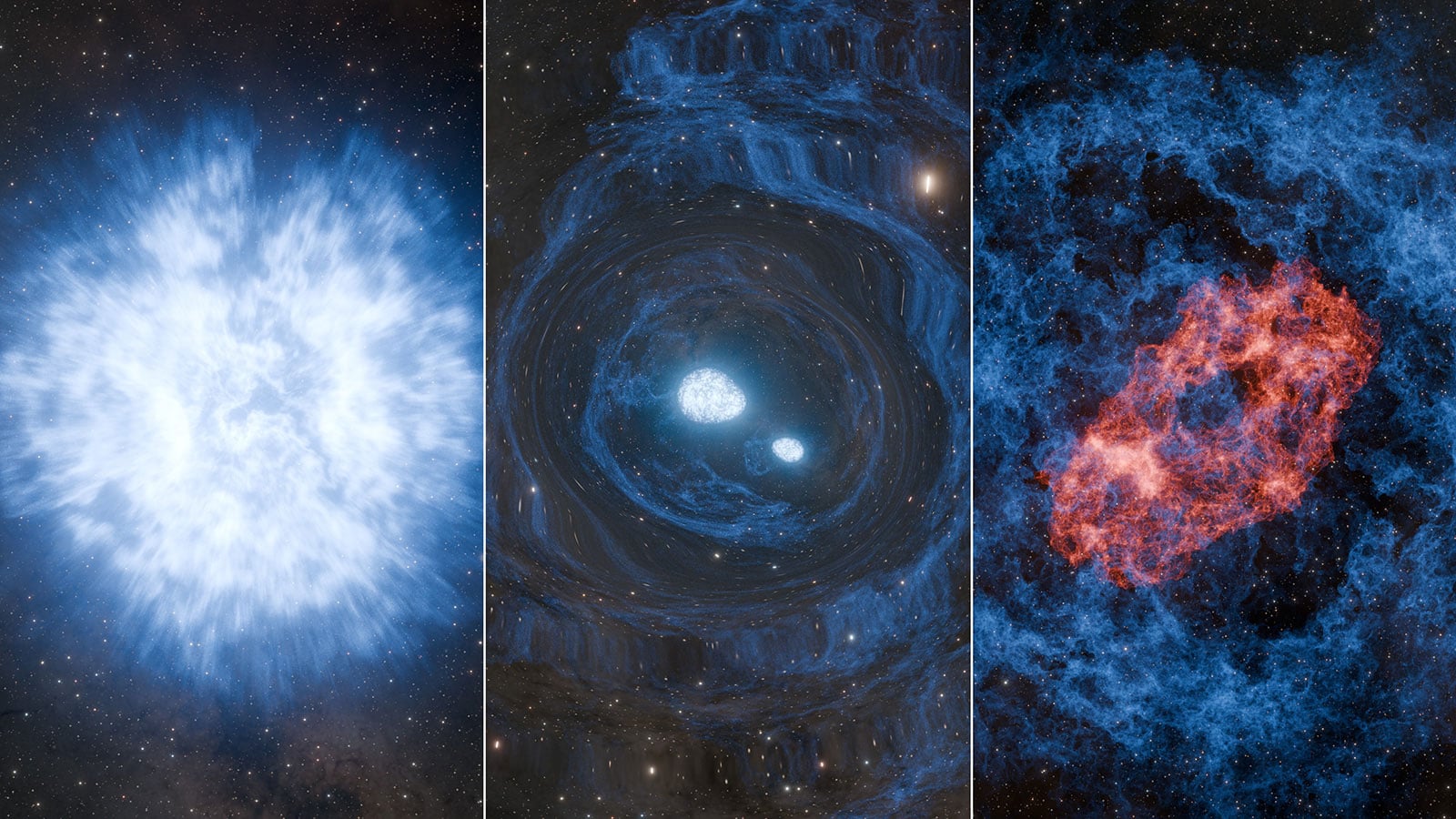

Artist's impression of a hypothetical superkilonova. A massive star explodes in a supernova, giving birth to two neutron stars. These spiral towards each other before merging in a kilonova, producing gravitational waves and heavy elements like gold.

Credit: Caltech/K. Miller et R. Hurt (IPAC)

The AT2025ulz event was spotted in August 2025. It first showed an intense red glow that faded rapidly, strongly reminiscent of the only kilonova confirmed to date, GW170817. Yet, after a few days, its brightness began to increase again, adopting a blue hue and revealing the signature of hydrogen, characteristics typical of a supernova.

Furthermore, the LIGO and Virgo gravitational wave detectors recorded a signal from the same region of the sky (explanation at the end of the article). The data indicate that one of the objects involved in the collision had a mass lower than that of our Sun, which is unusual for a classic neutron star. This peculiarity immediately caught the researchers' attention.

This duality in the observations has divided the astronomical community. Some thought it was an ordinary supernova unrelated to the gravitational waves. Mansi Kasliwal, lead author of a study published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, however explains that the event did not perfectly match either of the two known models, pushing them to consider a hybrid explanation.

Thus, to account for such a low-mass neutron star, theorists propose two scenarios. The first, called fission, would see a fast-spinning star explode and split into two small remnants. The second, fragmentation, would involve the formation of a disk of matter around the collapsing star, whose clumps would aggregate to form a miniature neutron star.

From this perspective, if two of these newly formed neutron stars spiral and merge quickly, they could produce a kilonova whose glow would be masked by the debris of the initial supernova. This sequence, dubbed a superkilonova, remains to be confirmed. Future instruments, like the Vera Rubin Observatory or the Nancy Roman Space Telescope, will be essential to spot other similar events and test this hypothesis.

Gravitational Waves

Gravitational waves are ripples in spacetime that propagate at the speed of light. They are generated by violent cosmic events, like the merging of black holes or neutron stars. Predicted by Albert Einstein over a century ago, their direct detection was only achieved in 2015 by the LIGO observatory, marking a major advance in astrophysics.

These ripples are extremely faint, making their observation very difficult. Interferometers like LIGO, Virgo, or KAGRA use lasers over long distances to measure tiny variations in the length of their arms. When a gravitational wave passes, it stretches and compresses space in an imperceptible way, but these instruments are sensitive enough to capture it.

The detection of gravitational waves opens a new window on the Universe. Unlike light, they are not absorbed or deflected by matter, allowing observation of otherwise invisible phenomena, like the coalescence of compact objects at the heart of distant galaxies. They provide complementary information to that obtained by traditional telescopes.

The joint study of gravitational and electromagnetic signals, as for the AT2025ulz event, allows for a more precise reconstruction of the physics of these explosions. This helps in understanding the nature of the objects involved, their mass, their spin, and the processes at work during cataclysmic collisions.