🧲 Giant underground structures disrupt our planet's magnetic field

Follow us on Google News (click on ☆)

Researchers combined the analysis of fossilized magnetism in ancient rocks with detailed computer simulations. These models make it possible to go back in time 265 million years to reconstruct the past behavior of Earth's magnetic field.

Their observations demonstrate that two continental structures, located beneath Africa and the Pacific Ocean, act as giant hotspots. These masses of solid, extremely hot rock disrupt the circulation of liquid iron in the outer core. However, this circulation is the source of the magnetic field, like a giant dynamo.

Andy Biggin, who led this work, explains that beneath these hot zones, liquid iron tends to stagnate. This situation creates marked temperature contrasts that leave a signature on the magnetic field. Some of its characteristics appear to have remained remarkably stable for hundreds of millions of years.

This discovery changes our view of Earth's history and could help better interpret the formation of ancient continents, such as Pangaea, or even refine past climate models. Research continues to further decipher these magnetic signals that tell the story of our planet's evolution.

The geodynamo: engine of the magnetic field

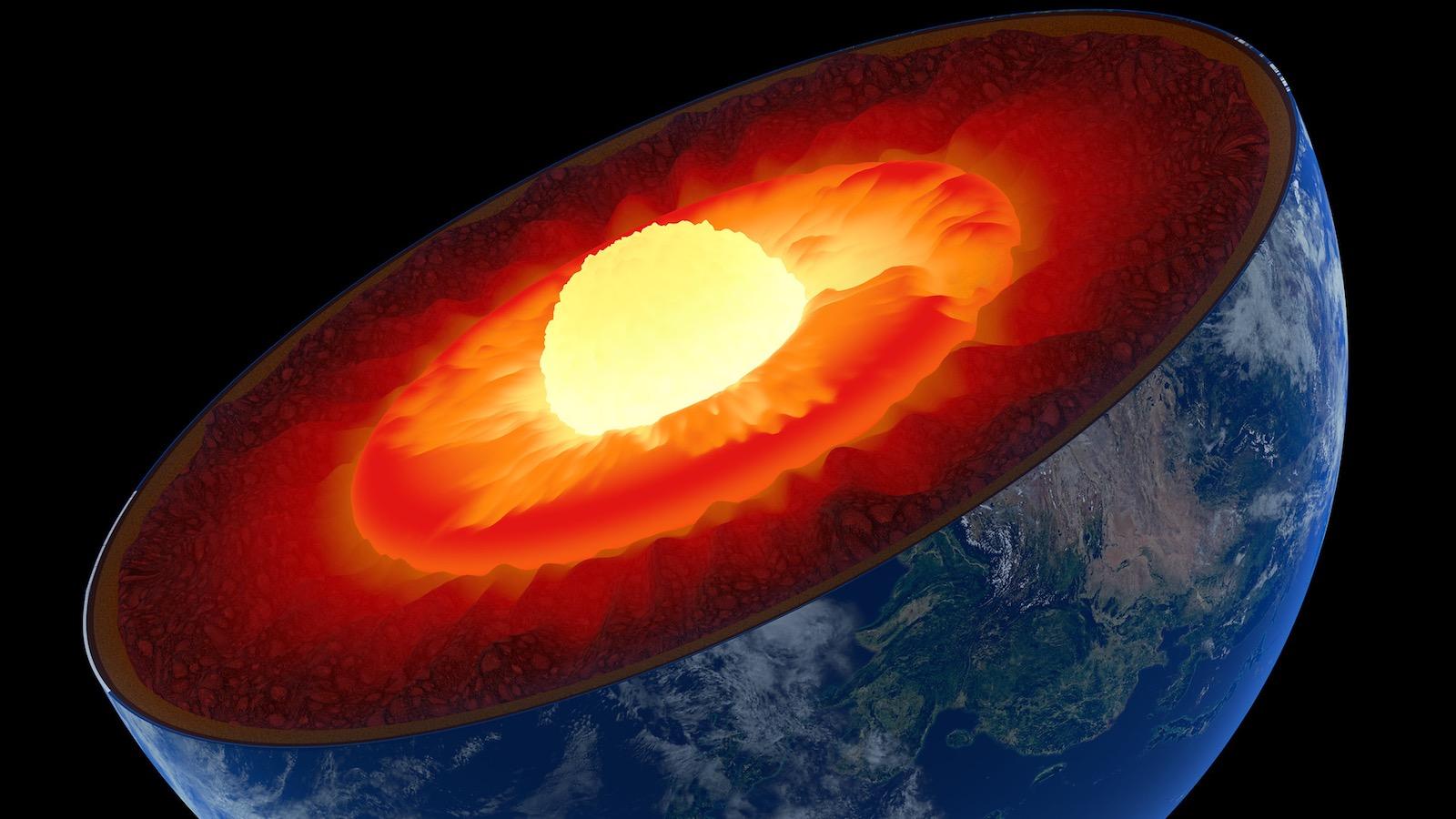

Earth's magnetic field is generated by a process called the geodynamo. It originates in the outer core, a layer of liquid iron and nickel located about 1,802 miles (2900 km) beneath the surface. The motion of this molten metal, combined with Earth's rotation, produces electrical currents that generate the field.

This phenomenon is comparable to the principle of a bicycle dynamo, but on a planetary scale. Heat from the solid inner core and the planet's gradual cooling fuel these convection movements. Liquid iron rises, cools, then sinks back down, creating a continuous loop.

The new study indicates that this system is not uniform. The presence of giant structures in the lower mantle alters how heat is expelled from the core. These local disturbances shape the circulation of the liquid metal and, consequently, the shape and strength of the resulting magnetic field.