Follow us on Google News (click on ☆)

An international team of scientists has made a discovery about animal communication, revealing that small mice use ultrasonic vocalizations, usually considered very private and short-range, to manage vast territories and interact with other groups. This research, recently published in the journal Current Biology, overturns our understanding of large-scale communication systems in mammals.

Traditionally, rodents' ultrasonic signals are thought of as intimate whispers, traveling only a few meters before fading away. Imagine trying to shout in a room and being heard at the other end of town! Yet, African striped mice (Rhabdomys pumilio) have developed a surprising strategy to overcome this limitation.

© ENES

An unexpected communication landscape

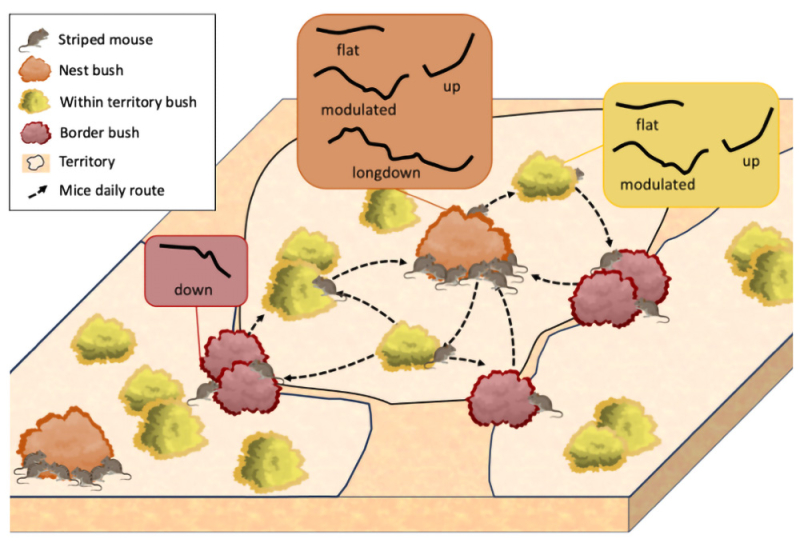

"We thought these ultrasounds were confined to close interactions within the same family group," explains Léo Perrier, former PhD student at Jean Monnet University Saint-Étienne and first author of the study. "But our field observations showed that these mice vocalized not only in their nests, but also in distant bushes at the heart of their territory and at the borders with neighboring groups."

The team deployed acoustic recorders across the territories of several mouse groups, revealing a surprising and localized use of different types of calls. The nest bushes, shelters for the family group, showed a rich and varied vocal repertoire. But at territorial borders, where encounters with outsiders are more likely, a specific type of call, the "down call," became predominant.

A vocal "passport" for each family group

That's not all. Using advanced neural networks to analyze vocalizations, scientists discovered that ultrasounds carry a signature unique to each mouse family, a true "vocal passport." Mice can thus distinguish members of their own family from their neighbors or completely unfamiliar individuals.

To test the importance of these signals, the team conducted field playback experiments. They broadcast vocalizations from family members, neighboring groups, or strangers, as well as control sounds without particular meaning. The responses were telling. Strangers' calls triggered rapid flight to the nest and increased vigilance. Those from neighbors caused moderate vigilance without immediate flight. Vocalizations from their own group, like the control sounds, had no significant impact on the mice's behavior.

These results prove that, despite their short range (the ultrasounds emitted by mice are no longer audible beyond two meters, or about 6.5 feet), ultrasounds play a fundamental role in group recognition and territorial defense. "It's a resolved paradox," adds Nicolas Mathevon. "Mice cannot send messages over long distances in one go, but by vocalizing strategically at key locations in their territory, they extend the functional range of their signals, creating a communication network at the landscape scale."

Beyond whispers: a new perspective on animal communication

This study opens new avenues for understanding how animals manage complex social dynamics in their natural environment. Striped mice demonstrate that even with significant physical constraints, appropriate behaviors can transform seemingly limited signals into powerful tools for social organization and survival. The whispers of mice are actually the pillars of a vast territorial intelligence system, comparable to bird songs. The only major difference for humans: they are in a range imperceptible to our ears.

This work was funded by Jean Monnet University Saint-Étienne, the Labex CeLyA, CNRS, Inserm and the Institut Universitaire de France.