✨ Two massive stars grazed past us, leaving still-visible traces

Follow us on Google News (click on ☆)

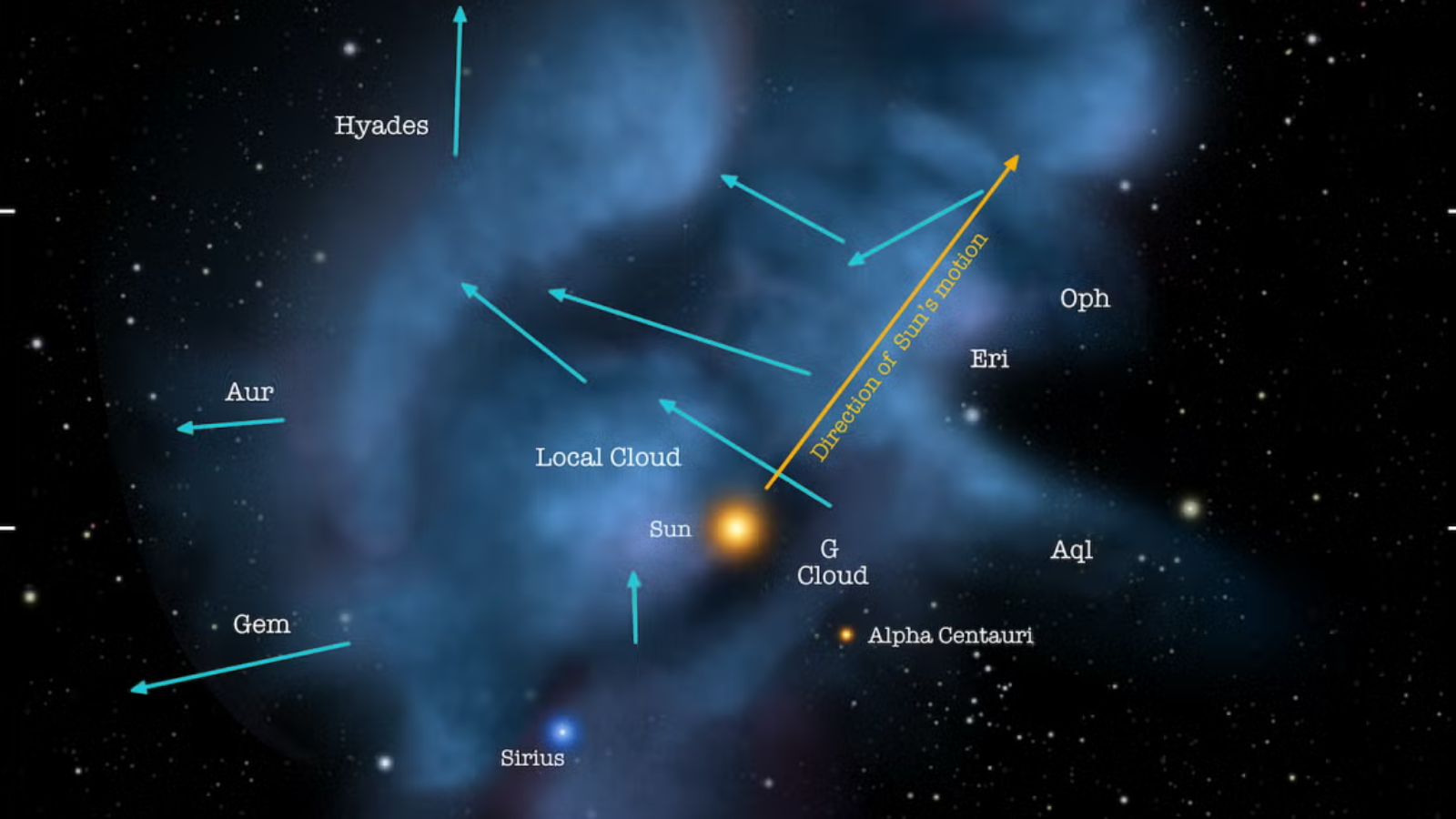

To reach these results, a team of researchers reconstructed the complex movements of the Sun, neighboring stars, and local interstellar clouds. The latter extend over about thirty light-years (around 18 trillion miles) and move through space, just like our star which races along at an impressive speed. According to Michael Shull of the University of Colorado Boulder, it's like solving a puzzle where all the pieces are moving at the same time. Their model allowed them to trace the passage of two stars in our neighborhood 4.4 million years ago.

Map of the local interstellar clouds near the Solar System, with blue arrows indicating their directions of motion. The yellow arrow shows the Sun's trajectory.

Credit: NASA/Adler/U. Chicago/Wesleyan

These two stars, named Epsilon and Beta Canis Majoris, are located in the constellation Canis Major and are currently 400 light-years (about 2.4 quadrillion miles) away from us. At the time of their passage, they came within about thirty light-years (around 18 trillion miles) of the Sun, a considerable distance for us but relatively small on a galactic scale. Much more massive and hotter than our star, they shone then four to six times brighter than Sirius, the brightest star currently in the night sky. Their intense ultraviolet radiation left a lasting mark on the nearby environment, a veritable scar of ionization (see below).

This mark corresponds to the ionization of hydrogen and helium atoms in the interstellar clouds. The stars' radiation stripped electrons from these atoms, giving them a positive electric charge. Scientists detected this phenomenon by observing that 20% of the hydrogen and 40% of the helium in these clouds were ionized, an abnormally high level. This solves an old puzzle about the composition of these gaseous regions.

The ionization of the clouds cannot be attributed solely to these two stars. Researchers believe at least four other sources of ultraviolet radiation contributed, including three white dwarfs and the hot local bubble. The latter is a relatively empty region of the interstellar medium, created by the supernova explosions of about ten stars long ago. These events heated the gas, emitting X-rays and ultraviolet light which also ionized the clouds around the Solar System.

The effect of this ionization is not eternal. Over time, atoms return to their neutral state by capturing free electrons, a process that could last a few million years. Meanwhile, the stars Epsilon and Beta Canis Majoris are nearing the end of their lives. Unlike the Sun, which will burn for billions of years more, these giants consume their fuel much faster and are expected to explode as supernovae in the near future on a cosmic scale (explanation at the end of the article).

Although too distant to threaten Earth, their explosions will offer a remarkable celestial spectacle, lighting up the sky in a spectacular yet harmless way. This study is published in The Astrophysical Journal.

Ionization of interstellar clouds

Ionization is a process where atoms lose or gain electrons, altering their electrical charge. In space, this phenomenon often occurs under the effect of energetic radiation, such as ultraviolet light emitted by hot stars. When these rays strike gas clouds, they can strip electrons from hydrogen and helium atoms, turning them into positively charged ions. This alteration leaves a signature detectable by astronomical instruments.

In the case of the local interstellar clouds, the observed ionization is particularly strong, with high percentages for helium. This indicates that powerful radiation sources acted upon these regions. Ionization affects the physical properties of the clouds, such as their temperature and density, which can influence the formation of new stars or the propagation of light through space.

Ionized atoms eventually return to a neutral state by capturing free electrons, a process that can take millions of years. During this period, the clouds remain marked by the event that ionized them, offering scientists a way to trace the history of stellar interactions in our galactic neighborhood.

Understanding ionization helps map energy flows in the Universe and assess how cosmic environments evolve over time. It is an important element for grasping the conditions prevailing in different regions of the galaxy, including around our Solar System.

Life cycle of massive stars

Massive stars, like Epsilon and Beta Canis Majoris, have a brief but intense existence. Much larger than the Sun, they burn their nuclear fuel at an accelerated rate, making them extremely hot and luminous. Their surface temperature can reach several tens of thousands of degrees, emitting powerful ultraviolet radiation that influences their environment. Unlike smaller stars, their life is measured in millions rather than billions of years.

At the end of their lives, these giants often undergo a spectacular explosion called a supernova. This event releases colossal energy, dispersing heavy elements into space and creating shock waves that shape surrounding gas clouds. The remnants of these explosions, such as white dwarfs or neutron stars, continue to emit radiation that contributes to the ionization of the interstellar medium.

Supernovae play an important role in the chemical enrichment of the galaxy, providing the materials necessary for the formation of new stars and planets. Their study allows astronomers to understand how elements like carbon or oxygen spread through the Universe, contributing to the diversity of stellar systems.

Observing these processes helps predict the future evolution of our galactic environment. For example, the imminent death of Epsilon and Beta Canis Majoris as supernovae will illuminate the Earth's sky without danger, offering a rare chance to see such an event from relatively close by.