Follow us on Google News (click on ☆)

These results, published in Nature Communications, shed new light on the role of star clusters in accelerating cosmic rays, participating in the redistribution of matter on a galactic scale and thus, in the formation of new stars.

Infrared observation, obtained by the James Webb Space Telescope; massive, bright stars distinguished with six large diffraction spikes and gas in red.

ESA/Webb, NASA & CSA, M. Zamani (ESA/Webb), M. G. Guarcello (INAF-OAPA) and the EWOCS team

Located more than 13,000 light-years from Earth, the Westerlund 1 star cluster has been on astrophysicists' radar for decades. This very young cluster in the Milky Way - only 4 million years old compared to the Sun's 4.5 billion years - concentrates hundreds of massive stars* within a diameter of only six light-years, whose combined power generates a powerful wind of elementary particles: cosmic rays.

A collaboration between LP2iB and the Max-Planck Institut, based on a combination of data from NASA's Fermi satellite and the ground-based H.E.S.S. telescope array, has just demonstrated for the first time that this cataclysmic particle wind manages to escape from the cluster in the form of a particle stream. This stream could eventually exit the galactic disk to feed the galactic halo and thus participate in the galaxy's chemical evolution.

It has been known for three years that Westerlund-1, which concentrates a mass equivalent to 100,000 suns, acts as a natural particle accelerator contributing to the acceleration of cosmic rays, composed mainly of protons, a small amount of heavier nuclei, and also electrons.

Indeed, the discovery by the H.E.S.S. telescopes in 2022 of gamma-ray emission encompassing Westerlund-1, with an energy approaching teraelectronvolts (TeV), had betrayed the presence of electrons accelerated to dizzying speeds at the outer edges of the cluster by the collective magnetic winds of its many massive stars.

It is the gamma rays generated by the interaction between electrons and photons through a process called "inverse Compton scattering" that are indirectly detected by the H.E.S.S. telescope array, allowing scientists to infer the presence of cosmic rays. But one peculiarity intrigued researchers: this radiation did not appear only as a ring around the cluster, but also as a "tail" extension, directed out of the galactic plane.

"It is in this context that I worked with the Max-Planck Institut," explains Marianne Lemoine, a researcher at LP2I Bordeaux and lead author of the article. "They wanted me to study this H.E.S.S. observation in light of data from the Fermi satellite, which had also observed gamma-ray sources near Westerlund-1." "Indeed, Fermi detected gamma-ray emissions in the gigaelectronvolt (GeV) range in a region extending far beyond the cluster, up to several hundred light-years beyond. I then demonstrated that these gamma-ray emissions did not come from isolated sources but should be understood as a single phenomenon. That it is in fact the extension of the gamma-ray radiation detected by H.E.S.S., escaping from the cluster in the form of a particle stream that propagates in the interstellar medium for over 500 light-years."

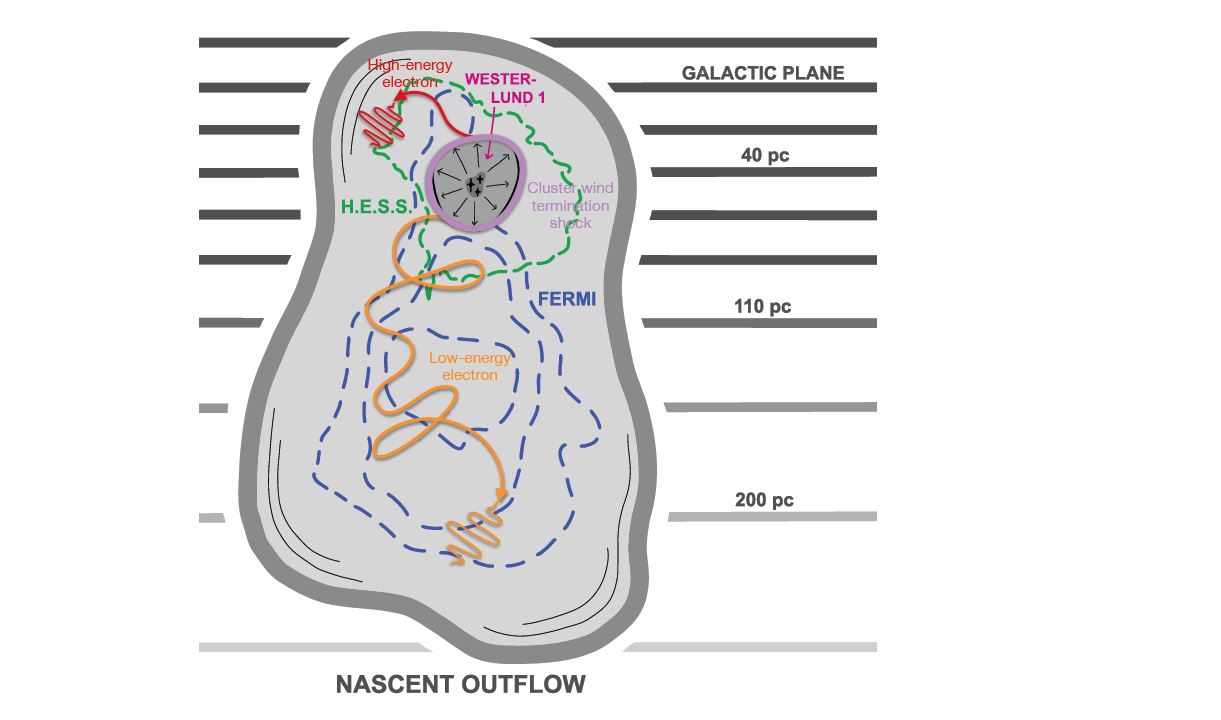

Following this analysis, the Max-Planck Institut team worked to model the phenomena at work in this long radiation trail. According to their model, the electrons accelerated at the cluster's margins are propelled out of it perpendicular to the galaxy's plane, towards the galactic halo. The most energetic electrons quickly lose their energy and are therefore only visible in the immediate vicinity of the cluster, where they produce the high-energy gamma radiation (in the TeV range) detected by H.E.S.S.

Farther from the cluster, only electrons that have already lost some of their energy are detected: these are the ones responsible for the more diffuse gamma emission observed by Fermi. This modeling of the cosmic ray stream received further confirmation when a study of the interstellar gas in this region of the galaxy revealed an area depleted in matter, as if the electron stream had literally blown the surrounding material away.

Cosmic electrons are accelerated at the terminal shock of the cosmic wind (in pink). High-energy electrons quickly lose their energy and emit TeV gamma rays measured by H.E.S.S.. Lower-energy electrons are carried along the outflow and generate GeV gamma rays detected by Fermi-LAT.

"With H.E.S.S. and Fermi, we can only indirectly detect the electrons, which produce the gamma rays. The protons remain invisible here, because the region around the cluster is very poor in matter: protons can only interact with other protons, and for lack of sufficient targets, they do not produce a detectable signal," adds Marianne Lemoine. "However, it is very likely that this stream, if it manages to continue its propagation to the galactic halo, will eventually reach other regions of the galactic plane, thus contributing to the redistribution of matter in the Milky Way and thereby to the formation of new stars and new clusters."

This combined analysis of Fermi and H.E.S.S. data thus represents a major advance in understanding how galaxies regulate themselves and evolve over time. Future observations by the CTAO Observatory, under construction in Chile and the Canary Islands, will determine whether Westerlund-1 is a unique case in the galaxy or a representative model for many other massive clusters in the Universe.

Note:

* In the Sun's neighborhood, there is on average less than one star in the same volume.