Follow us on Google News (click on ☆)

Junk food and its effects on the brain

Obesity is on the rise in children and adolescents. It is often accompanied by neurological disorders, such as memory or attention problems, which are still poorly understood and difficult to treat. One possible cause: excessive consumption of foods high in fat and sugar, which could disrupt brain development.

Illustration image Pixabay

In humans, it is difficult to prove with certainty that a poor diet causes cognitive disorders because studies are often limited by sample size and duration. Furthermore, they lack the resolution to prove causality between eating habits and cognitive health trajectory.

Previous studies on animal models have shown that unrestricted junk food disrupts innate biological rhythms that influence hormonal secretions, neuronal structure, and the functioning of brain regions that encode, store, and recall memories.

When meal timing becomes as important as their content

Some studies, in particular, have shown in adult mice subjected to junk food the importance of the fasting period on memory. But no study has yet established a link between fasting and memory abilities during the transition from childhood and adolescence to adulthood. Yet this knowledge is important because there is an explosion in the number of children and adolescents using social media late at night, which delays mealtimes and leads to overconsumption of junk food.

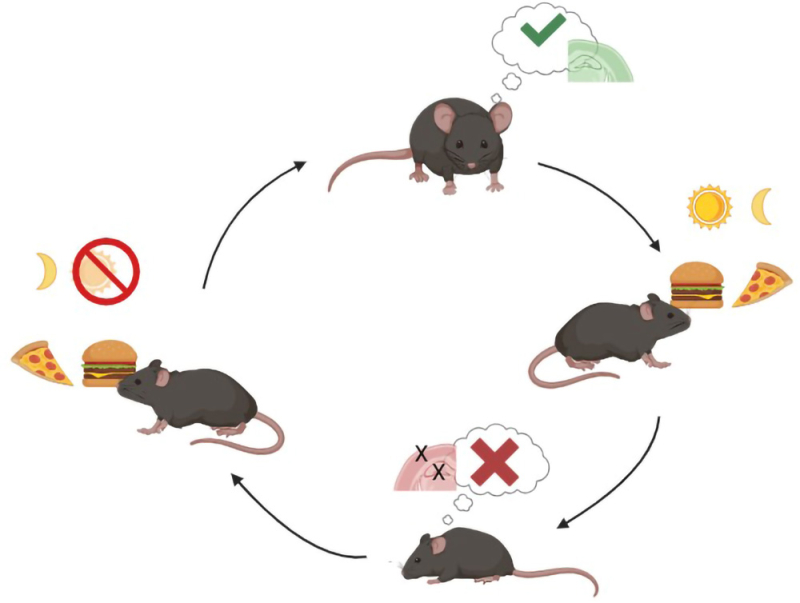

This study, published in the journal eBioMedicine, therefore aims to shed light on this lack of knowledge. For this study on eating rhythms, young mice were fed in two ways for 14 weeks:

- Either with junk food available at any time of day,

- Or with the same foods but only during their active period.

Junk food consumed ad libitum decouples the cortico-hippocampal axis necessary for memory recall.

The cortex becomes hypoactive when the hippocampus is hyperactive. Intermittent fasting applied for 4 weeks to a subgroup of individuals fed junk food was sufficient to rebalance cortico-hippocampal functions and improve memory performance. The common denominator in these disruptions caused by poor eating habits targets the circadian secretion of hormones and their impact on neuroplasticity.

© Prabahan Chakraborty

A link between memory, hormones, and eating rhythms

The scientists observed cognitive functions, connections between neurons, hormones, and energy expenditure. Mice fed ad libitum showed memory disruption with dysregulation of connections between two key brain areas: the cortex and the hippocampus, the seat of memory. This effect is linked to resistance to hormones, glucocorticoids, which are essential for memory. In contrast, mice fed according to their biological rhythm maintained good cognitive performance, despite an identical diet in calories and quality.

Furthermore, the study shows that mice carrying mutations causing glucocorticoid resistance mimic the effects of unrestricted junk food and cancel the benefits of intermittent fasting. To establish the cause-and-effect relationship, the scientists used genetically modified mice to inhibit or activate the relevant neural networks. They were thus able to show that the disruption caused by junk food is characterized by lower cortical function associated with higher hippocampal activity. Similarly, the absence of an effect observed in mice subjected to intermittent fasting requires the coactivation of the cortico-hippocampal axis.

The results will need to be validated in humans before informing health advice and school policy.