🧠 A New Theory to Explain Consciousness

Follow us on Google News (click on ☆)

The debate on the origins of thought has long pitted two schools against each other. On one side, computational functionalism views the mind as a form of information processing, independent of its physical substrate. On the other, biological naturalism considers consciousness to be inseparable from the living matter of the brain.

Illustration image Pixabay

There is, however, a middle path, referred to as 'biological computationalism', explained in a publication in Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. The main idea hinges on the inadequacy of the classical computing model to describe brain operations. Unlike conventional machines that sharply separate software from hardware, this distinction blurs in the cerebral organ. Rather than forcing a computer analogy, it seems essential to broaden our concept of what constitutes a computation operation to understand how the mind could emerge from other substrates.

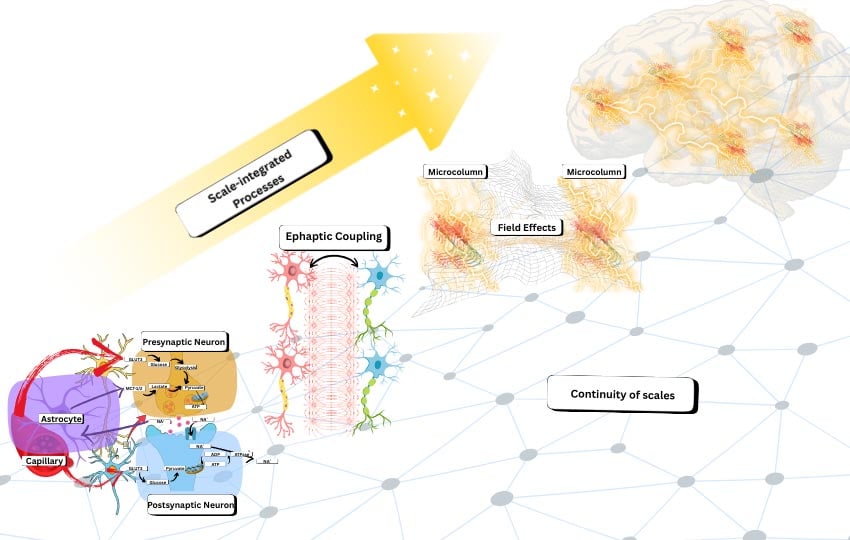

Biological computation has three fundamental traits. First, it is hybrid, mixing discrete events, such as neuronal firing, and continuous processes, such as electric fields or chemical gradients. The brain is neither purely digital nor simply analog. It forms a system where continuous dynamics influence discrete events, which in turn modify continuous processes through feedback, creating a permanent loop of interactions.

Furthermore, this computation is inseparable from scales. In a classical computer, a clear boundary can be drawn between software and hardware. In the brain, this boundary does not exist. Causal interactions extend simultaneously across many levels, from ion channels to neural circuits, up to global brain dynamics. Modifying what one might call the physical implementation directly alters the computation itself, as the two are tightly interwoven.

In conventional computation, one can draw a sharp line between software and hardware. In the brain, there is no such separation between different scales. Everything influences everything, from ion channels to electric fields, from circuits to global brain dynamics.

Credit: Borjan Milinkovic

Finally, biological computation is anchored in metabolism. The brain operates under strict energy limits that influence its organization at all levels. These constraints are not just a technical detail. They affect what the brain can represent, how it learns, which patterns remain stable, and how information is coordinated and routed. The tight coupling between scales thus appears as an energy optimization strategy, allowing for flexible and robust intelligence despite these severe limits.

This perspective shows the limits of current artificial intelligence models. Even the most high-performing AI systems primarily simulate functions through numerical procedures on hardware designed for a very different processing style. In the brain, computation occurs in real physical time. The continuous fields, ion flows, dendritic integration, or electromagnetic interactions are not mere biological details that can be ignored. According to this approach, these processes are the building blocks of cerebral computation, enabling real-time integration, robustness, and adaptive control.

This proposal does not defend the idea that consciousness is reserved for carbon-based life. The argument is more nuanced. If consciousness depends on this particular type of computation, then it might require a biologically-styled computational organization, even if it is implemented in new substrates. The question is not whether a system is literally biological, but whether it performs the right type of hybrid, scale-inseparable, and energy-constraint-anchored computation. This redefines the goal of creating synthetic minds, steering research toward the design of physical machines where computation is intrinsic to the system's dynamics, not an abstract layer added on top.