Follow us on Google News (click on ☆)

They then developed a method to study them and identified 138 new main-belt asteroids. These celestial bodies, ranging from the size of a bus to that of several stadiums, represent the smallest asteroids ever detected in this region of space.

Thanks to this new approach, researchers can now spot asteroids as small as 10 meters (33 feet) in diameter, paving the way for an in-depth exploration of small objects in the solar system. This advancement is crucial for better understanding the history of the solar system and for improving the tracking of potentially hazardous asteroids, thereby enhancing planetary security.

This study was published in the prestigious journal Nature, under the title "JWST sighting of decameter main-belt asteroids and view on meteorite sources".

Observing main-belt asteroids, a challenging quest

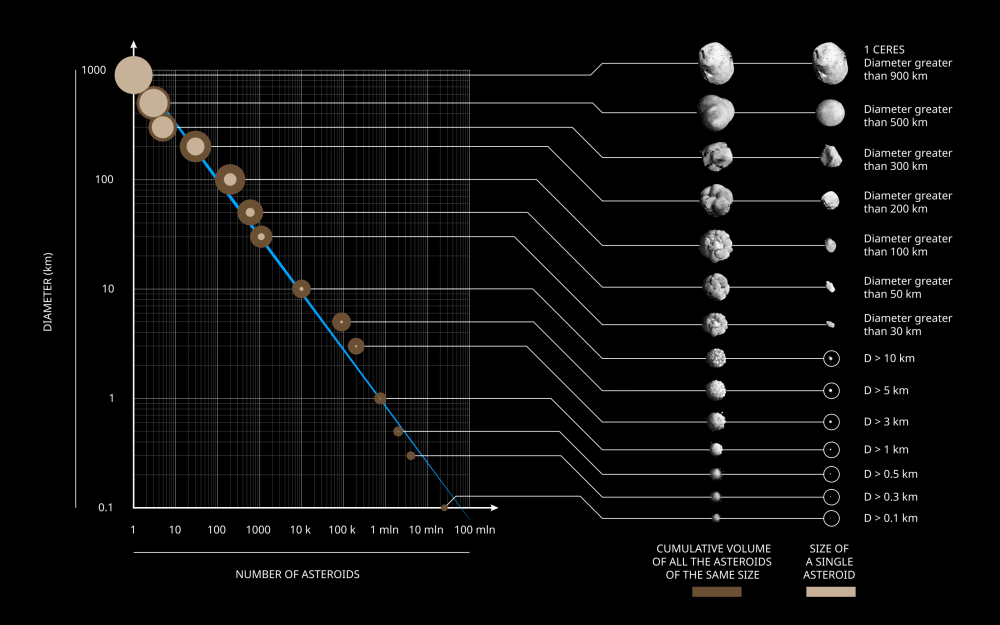

The asteroid responsible for the extinction of the dinosaurs measured about 10 kilometers (6.2 miles) in diameter, equivalent to the width of Brooklyn. Such an impactor strikes Earth very rarely, with an estimated frequency of once every 100 to 500 million years. In contrast, much smaller asteroids, comparable to the size of a bus, can hit Earth much more frequently, every few years, because they are far more numerous (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 - Size distribution of main-belt asteroids, predominantly populated by small asteroids, while large asteroids are much rarer, following a power law.

Credits: Marco Colombo — DensityDesign Integrated Course Final Synthesis Studio

These asteroids, referred to as "decametric" due to their diameter of about ten meters (33 feet), are nonetheless capable of generating shock waves that can cause regional damage, as seen during the 1908 explosion in Tunguska, Siberia, or the 2013 event in the skies of Chelyabinsk in the Urals.

These asteroids primarily originate from the main belt, located between Mars and Jupiter, where millions of celestial bodies orbit. Cataloging these asteroids is fundamental, both for scientific research—to elucidate the origins and evolution of the solar system—and for planetary security—by identifying near-Earth objects, asteroids whose orbits cross Earth's and could pose a threat.

However, until recently, available instruments could only detect asteroids in the main belt measuring at least one kilometer (0.62 miles) in diameter. This limit is largely insufficient, given that the majority of asteroids in this region are much smaller. Moreover, these small asteroids have an increased likelihood of leaving the main belt and becoming near-Earth objects, thereby raising the risk of causing significant damage to our planet. A better ability to detect these small bodies is therefore crucial to address these challenges.

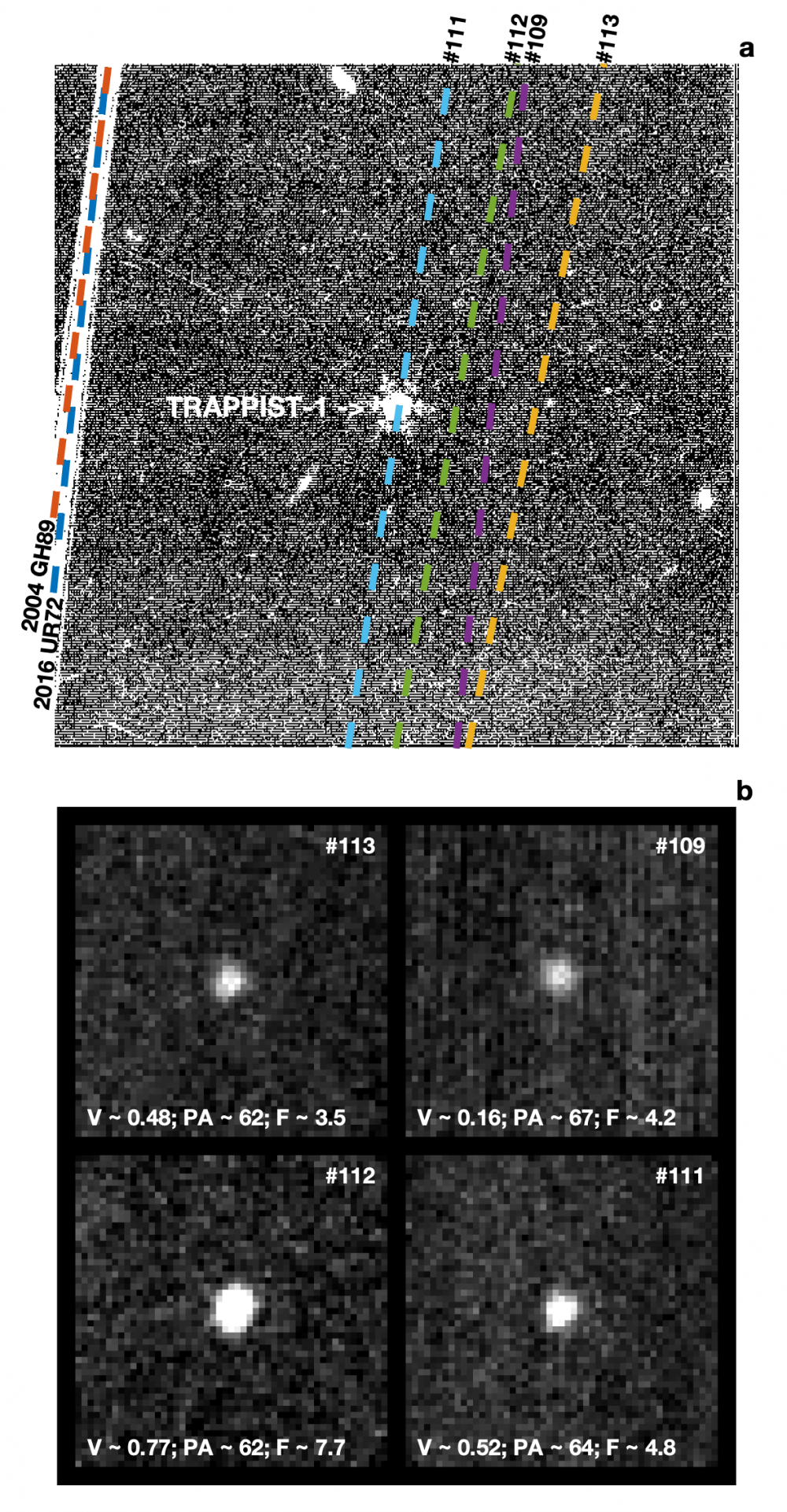

Figure 2 - Discovery of new asteroids with the JWST during the observation of the TRAPPIST-1 system.

Credits: Burdanov, de Wit et al., 2024, Nature.

a. Stacking of 500 images of the ultra-cool star TRAPPIST-1.

Two known asteroids (2004 GH89 and 2016 UR72) stand out with a white trail visible on the left side of the image. Their brightness is such that they appear in individual images. In contrast, four other asteroids (#113, #109, #112, and #111), previously unknown, only reveal their presence after stacking hundreds of images. Their trajectories are indicated by dotted lines.

b. Images of the four new asteroids (#113, #109, #112, and #111) along with their respective properties: velocity (V, in arcsec/min), position angle (PA, in degrees), and flux (F, in ?Jy). These asteroids were discovered using the "shift and stack" technique, which involves recentering successive images on the objects' positions and then superimposing them. This method improves the signal-to-noise ratio, revealing objects invisible in a single image.

From nuisance to opportunity: when "parasites" become a scientific boon

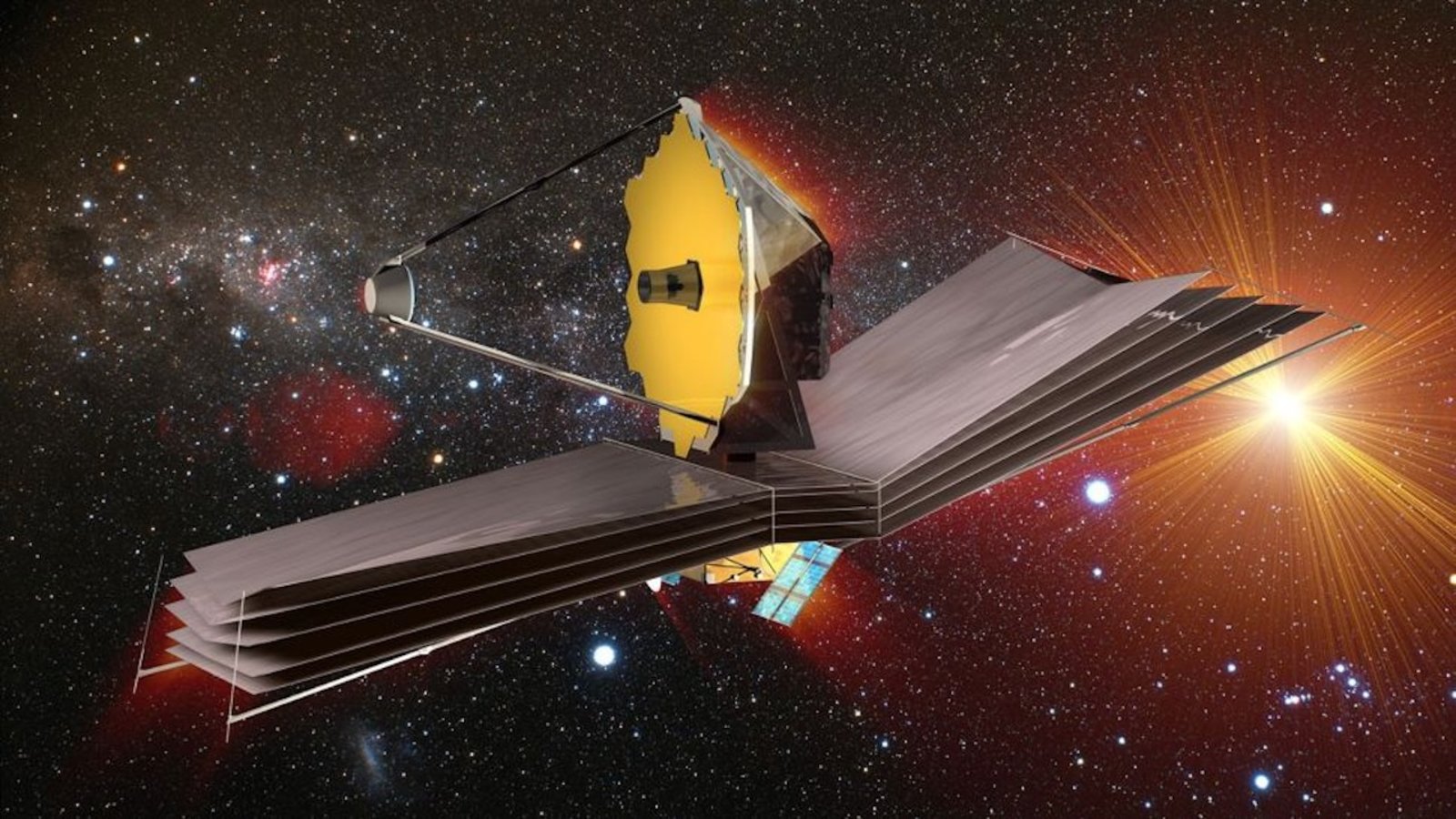

As part of the program titled "TRAPPIST-1 Planets: Atmospheres Or Not?", co-led by the Astrophysics Department (DAp) of IRFU at CEA Paris-Saclay, the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) observed the TRAPPIST-1 exoplanetary system using the MIRI instrument. The goal was to study the phase curve of the first two planets, TRAPPIST-1 b and c, to track the evolution of their luminous flux over a complete orbit. This type of observation allows measuring the thermal emission from different sides of each planet and studying the distribution of heat on their surfaces, aiming to confirm or rule out the presence of an atmosphere.

To cover a full orbital period of planets b and c (1.5 days and 2.42 days, respectively), the observations spanned about 60 hours, making it the longest continuous observation program of a star conducted by the JWST for exoplanet studies, explains Elsa Ducrot, a researcher at the Astrophysics Department of CEA, co-leader of this observation program and co-author of this study.

During the analysis of these observations, an international research team, led by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT, USA) and including DAp, noticed that they were contaminated by asteroids crossing the field of view (see figure 2a). Although the field is very small (56.3" × 56.3"), many asteroids regularly appear in it, as TRAPPIST-1 is located in the ecliptic plane, where solar system objects, particularly those from the main belt, reside.

"For most astronomers, asteroids are considered sky nuisances: they cross the field of view and disrupt the data," notes Julien de Wit, co-lead author of this study and researcher at MIT.

However, instead of simply cleaning the data of these "parasites," as is usually done, the researchers wondered if this information could be used to identify asteroids in our own solar system. To do this, they used a technique called "shift and stack," developed in the 1990s. This method involves shifting and stacking multiple images of the same field of view to bring out a faint object hidden in the noise.

A new window into space

The presence of TRAPPIST-1 in the MIRI instrument's field represents a real opportunity, as its sensitivity in the mid-infrared makes it a perfectly suited tool for observing asteroids. In visible light, only sunlight reflected by the asteroid is detectable. If the asteroid is small and distant, the luminous flux becomes extremely weak. In contrast, in the infrared, light emitted directly by the asteroid is captured, significantly increasing the observable flux. Thanks to its large collecting power and infrared vision, the JWST proves to be an ideal instrument for detecting small bodies in our solar system.

By processing over 10,000 images of the TRAPPIST-1 system taken by the JWST, the team identified eight previously cataloged main-belt asteroids. By further analyzing the data, they managed to detect 138 new asteroids, all with diameters of a few tens of meters (see figure 2b). These objects represent the smallest asteroids ever observed in this region to date, enabling the exploration of a new population of asteroids (see figure 3).

"This is a whole new region of space we are exploring thanks to modern technologies," adds Artem Burdanov, lead author of the study and researcher at MIT. "This is a great example of what we can achieve by analyzing data differently. Sometimes, the results exceed our expectations, and that's the case here."

The researchers plan to use this method to identify and track new near-Earth objects, asteroids whose orbits cross Earth's.

"We have already been able to detect near-Earth objects measuring up to 10 meters (33 feet) when they were very close to us," explains Artem Burdanov. "Now, we have a way to spot these small asteroids much farther away, allowing us to perform more precise orbital tracking, essential for planetary defense."

Figure 3 - Artist's illustration of a myriad of small main-belt asteroids revealed by the JWST.

Credits: Ella Maru, Ella Maru Studio