Follow us on Google News (click on ☆)

The Vera C. Rubin Observatory, located atop a Chilean mountain, photographed in August 2024. With its giant camera, it promises to revolutionize our understanding of the cosmos.

Credit: RubinObs/NOIRLab/SLAC/NSF/DOE/AURA/A. Pizarro D.

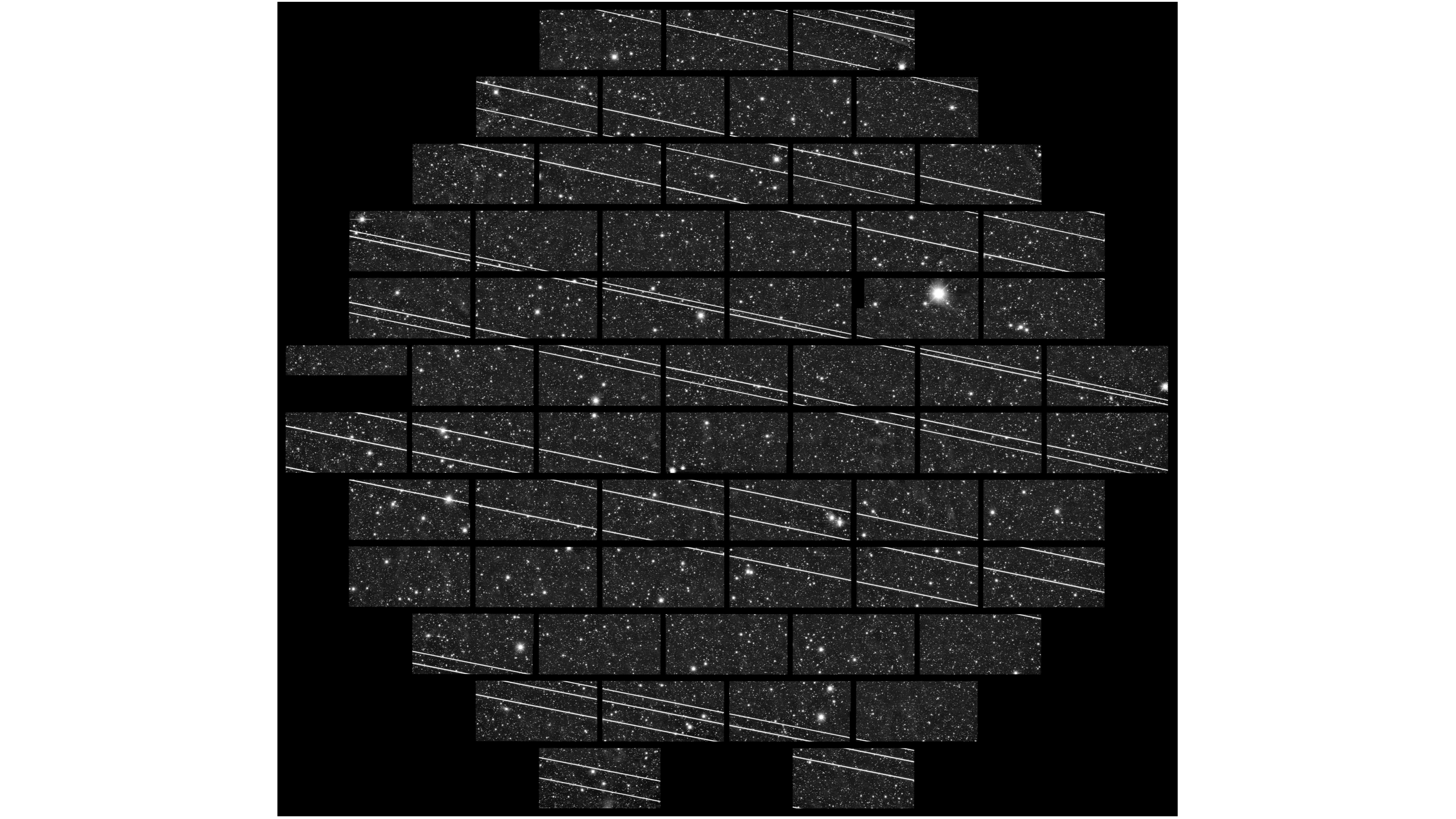

The Vera Rubin Observatory, equipped with a 3,200-megapixel camera, is designed to map the Universe with unprecedented precision. However, the proliferation of satellite megaconstellations, such as SpaceX's Starlink, threatens to compromise this mission. These satellites leave trails that risk "burning" astronomical images.

Scientists have developed algorithms to distinguish satellites from genuine celestial phenomena. Despite these efforts, up to 40% of images could be affected, representing a significant waste of resources. Satellites not only dazzle instruments but can also be mistaken for astronomical events.

Initiatives to reduce satellite brightness, such as the use of special paints, offer hope. However, the effectiveness of these solutions remains unproven. The balance between technological progress and preserving the night sky is now more than ever a major challenge for astronomers.

An image of 19 Starlink satellites shortly after their launch in November 2019, captured by the Víctor M. Blanco telescope.

Credit: CTIO/NOIRLab/NSF/AURA/DECam DELVE Survey