Follow us on Google News (click on ☆)

More than 28% of the people tested believe it is good for their health to regularly consume this fictional brand of white wine which displays a nutrition information table. This percentage is 17% when the label does not have a nutrition table. — Lana Vanderlee

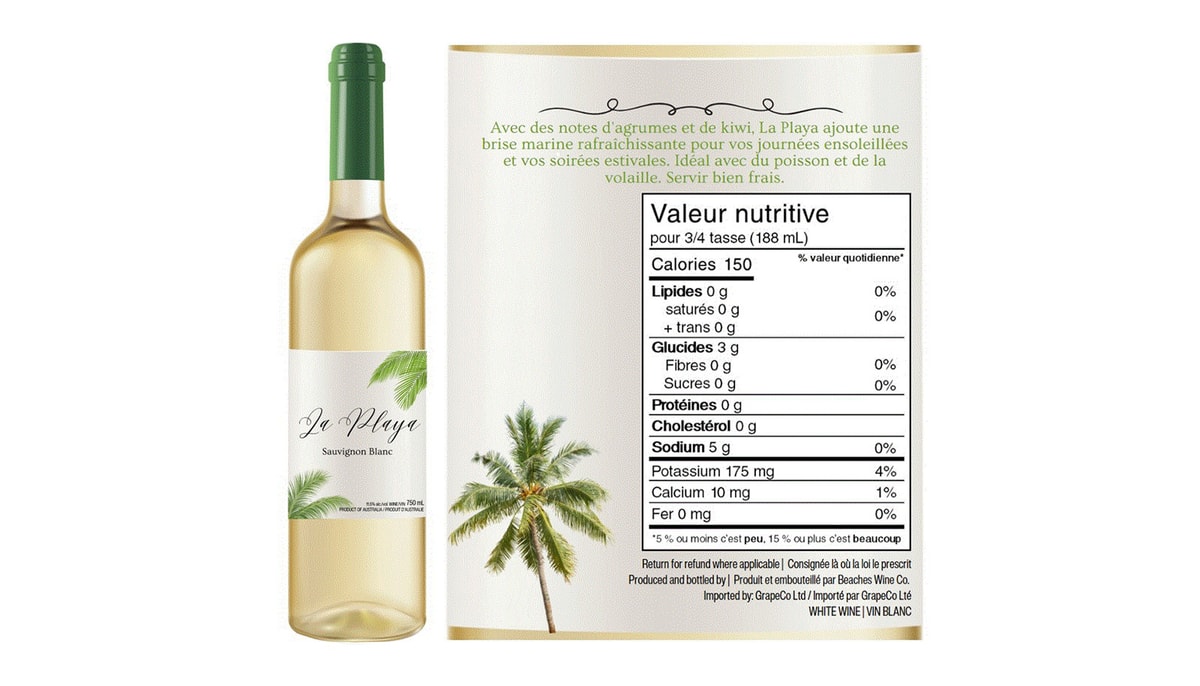

In Canada, drinks with an alcohol content below 0.5% must display a nutrition facts table on their container. Drinks containing more than 0.5% alcohol are exempt from this obligation, unless a nutritional claim appears on the label. When a table is present, regulations require it to have the same format as the one found on foods.

"Some alcoholic products, including ready-to-drink beverages, choose to display a nutrition facts table, but the vast majority of alcoholic drinks do not," points out Lana Vanderlee, a professor in the School of Nutrition at Université Laval and a researcher at Université Laval's NUTRISS Centre.

Several approaches have been considered to improve the transparency of nutritional information on alcoholic products, she adds. "Consumers have a right to know what these products contain, but we still don't know what the best way to do that would be."

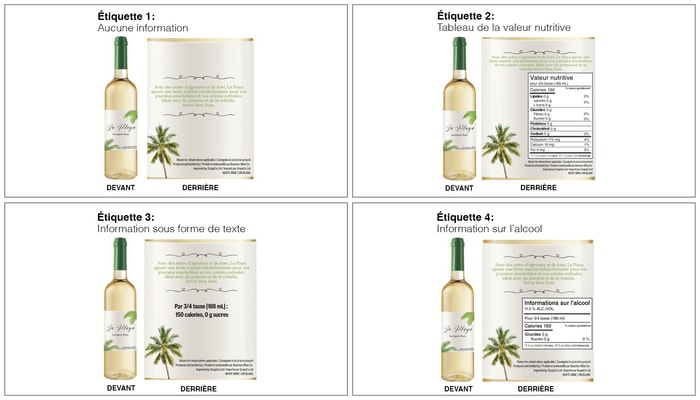

To advance knowledge in this area, Professor Vanderlee and three colleagues from Ontario conducted an online survey of 3880 people. For the study, four labels, intended for the back of a wine bottle, were designed.

The first displayed no nutritional information, while the second featured a standard nutrition information table. Labels 3 and 4 presented essentially the same information (calories, sugar), but one in text form and the other in a table whose title did not refer to nutrition.

Each person who participated in the study had to view one of these four labels and answer the question "Is it good or bad for your health to regularly drink this wine?". — Lana Vanderlee

"Labels 3 and 4 are similar to proposals currently under consideration in the United States," specifies Professor Vanderlee. "Canada has not begun consultations on this, but what happens in the United States in the food sector often has repercussions later on this side of the border."

Each person who took part in the study had to view one of the four labels and subsequently answer the question "Is it good or bad for your health to regularly drink this wine?".

The analyses show that label 2, the one with the nutrition information table, received the most positive responses, at 28%. Label 1, without information, received 17%. Labels 3 and 4 received 24% and 18% positive responses, respectively.

"The presence of nutritional information on the label leads more people to conclude that the product can be good for your health," observes Professor Vanderlee. "This effect is more pronounced for the label displaying the nutrition information table of the same type as those on foods."

Alcohol is not a food

These results are somewhat puzzling, the researcher admits. "I have always defended the idea that people have a right to know what they are consuming. However, in the case of alcoholic beverages, nutritional information creates the false impression that these products can be good for your health, which is not the case. Alcohol is a major factor in mortality and diseases, including seven types of cancer, and there is no safe minimum consumption threshold."

If Canada were to choose a label model to apply to alcoholic beverages, which of the four proposals tested should be adopted? "We should avoid labels that give the impression that alcohol is a food because it is not. The most important thing would be to ensure the label carries a health warning about the harms of alcohol, like those found on tobacco or cannabis products."

Lana Vanderlee is the first author of the study published in Preventive Medicine. The other signatories are Christine White and David Hammond, from the University of Waterloo, and Erin Hobin, from the University of Toronto.