Follow us on Google News (click on ☆)

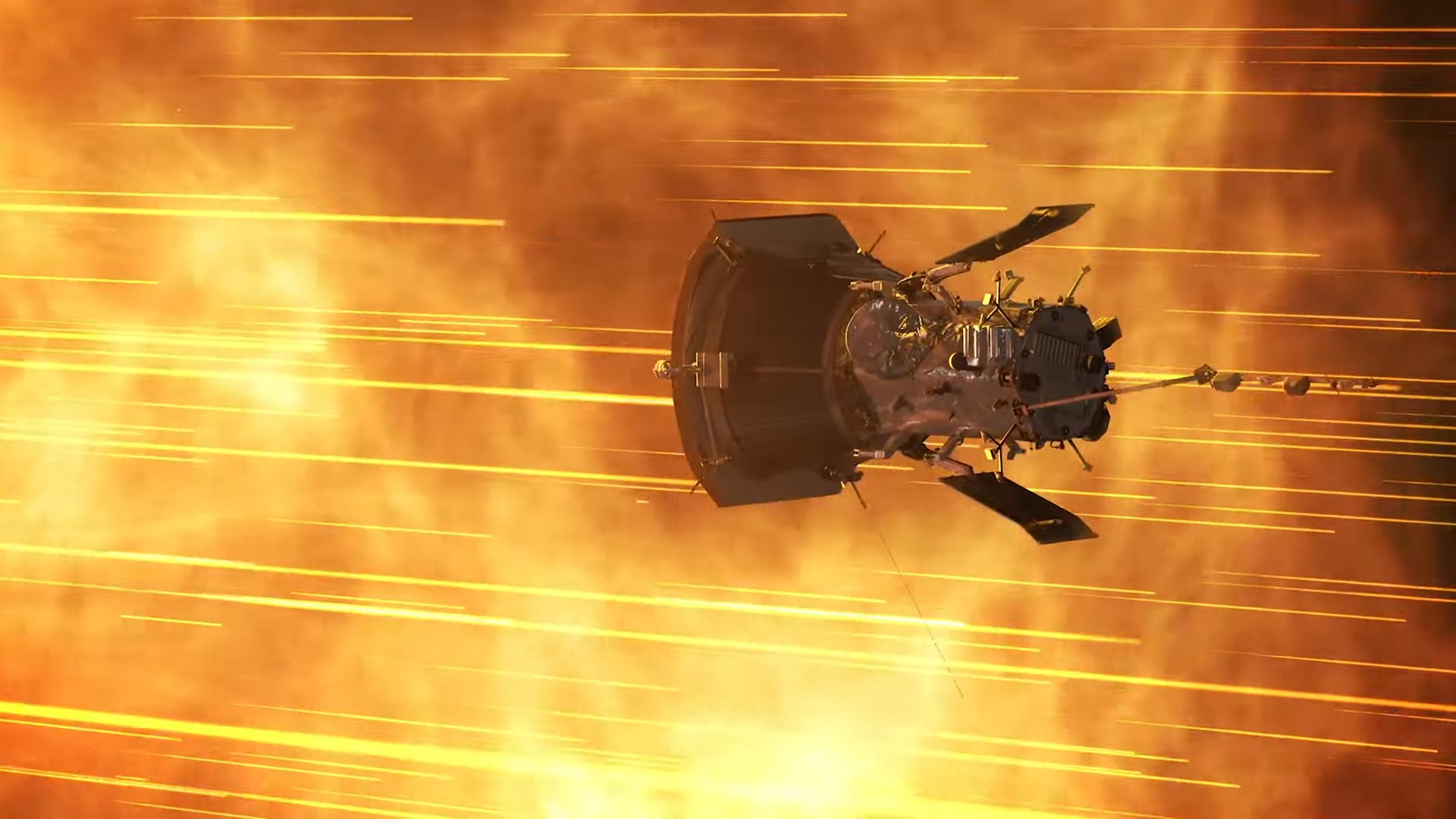

Engineers anticipate an unprecedented close approach this morning on December 24, accompanied by a record-breaking speed for a human-made object.

Credit: NASA GSFC/CIL/Brian Monroe

According to estimates, Parker could travel at over 435,000 mph (700,000 km/h) during this flyby. This performance places it as the fastest object ever created by humans. Subjected to temperatures exceeding 2500°F (1400°C), the probe is protected by a thermal shield that insulates its instruments. Technicians explain that this carbon composite shielding efficiently dissipates heat, preserving the onboard electronics.

Since 2021, the probe has successfully crossed the solar corona. Researchers are thus directly observing coronal winds, the high-speed flows of particles ejected by our star. The team states that each flyby yields new data to understand the extreme energy and temperature of this corona.

The probe uses Venus's gravitational assist to get closer to the Sun. This method conserves fuel and slightly shifts the trajectory towards the corona. Specialists emphasize that without these planetary flybys, achieving such close proximity would be nearly impossible.

This period coincides with the intense activity of the solar cycle, often called the solar maximum. Sunspots, flares, and coronal mass ejections multiply during this time. The data collected provides insights into the evolution of the Sun's magnetic field, facilitating the prediction of space weather disturbances that could affect satellites or power grids.

The multiple flybys of Venus bring the probe closer to the Sun.

Credit: NASA/JPL/HORIZONS system

Project members mention that these observations recall the historic achievement of the first steps on the Moon. They consider this flyby a major advancement in the understanding of our star. The comparison underscores the significance of breaking new frontiers at the very heart of our Solar System.

The Parker Solar Probe is expected to perform several more close passes by 2025. Its fuel will eventually run out, leading to its slow disintegration under the Sun's forces. Researchers speculate that its shield might, however, remain in orbit for several millennia. This remnant will stand as a testament to the ingenuity applied to probing the solar corona.

It is harder to graze the Sun than to leave the Solar System

Reducing orbital velocity around the Sun requires a significant amount of energy. Gravitational laws dictate that to "descend" toward our star, a spacecraft must slow down substantially.

In contrast, moving farther away is achieved by gradually gaining speed. This is easier because the spacecraft uses Earth's initial momentum to escape.

To graze the Sun, one must counteract this velocity inherited from Earth's orbit around the star. Canceling this velocity demands more energy than propelling beyond the Kuiper Belt.

This is why the Parker Solar Probe relied on multiple Venus flybys to slow down and tighten its orbit, ultimately bringing it closer and closer to the Sun.