Follow us on Google News (click on ☆)

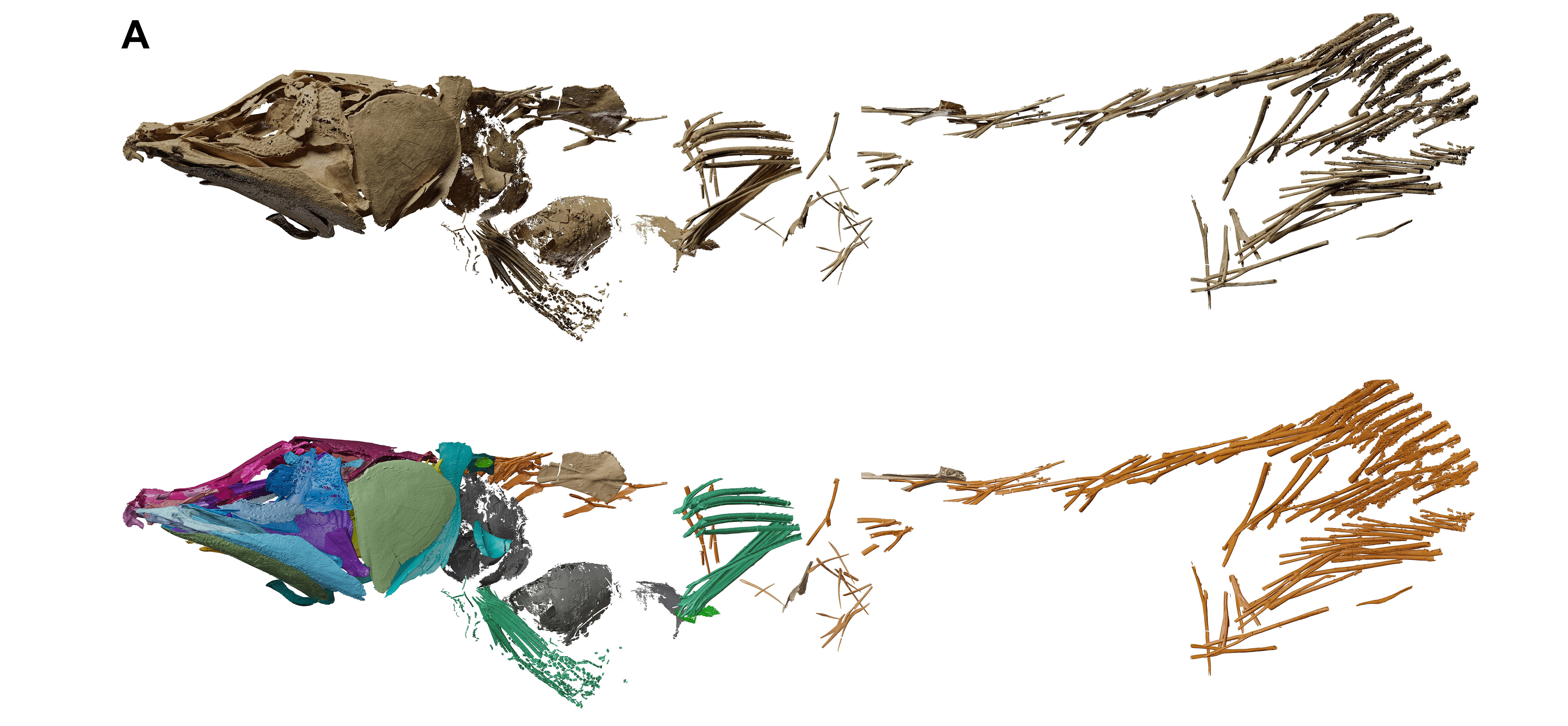

3D rendering of a Graulia branchiodonta specimen after the "digital removal" of the rock.

© L. Manuelli-MHNG

Coelacanths are strange fish currently known by only two species found along the East African coast and in Indonesia. A team from the Natural History Museum of Geneva (MHNG) and the University of Geneva (UNIGE) managed to identify an additional species with an unprecedented level of detail. This discovery was made possible through the use of the European Synchrotron in Grenoble, a particle accelerator enabling the analysis of matter. These findings were published in the journal PlosOne.

Fossilization is a process that preserves plants and animals in rocks over hundreds of millions of years. During this period, geological upheavals often damage the fossils, and paleontologists must put in significant effort and imagination to reconstruct organisms as they were when alive.

A team of paleontologists from MHNG and UNIGE, in collaboration with researchers from the Senckenberg Research Institute and Natural History Museum in Frankfurt am Main (Germany) and the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility in Grenoble (France), recently published research demonstrating that some 240-million-year-old coelacanth fossils preserve details of their skeleton so fine they had never been observed before using the synchrotron.

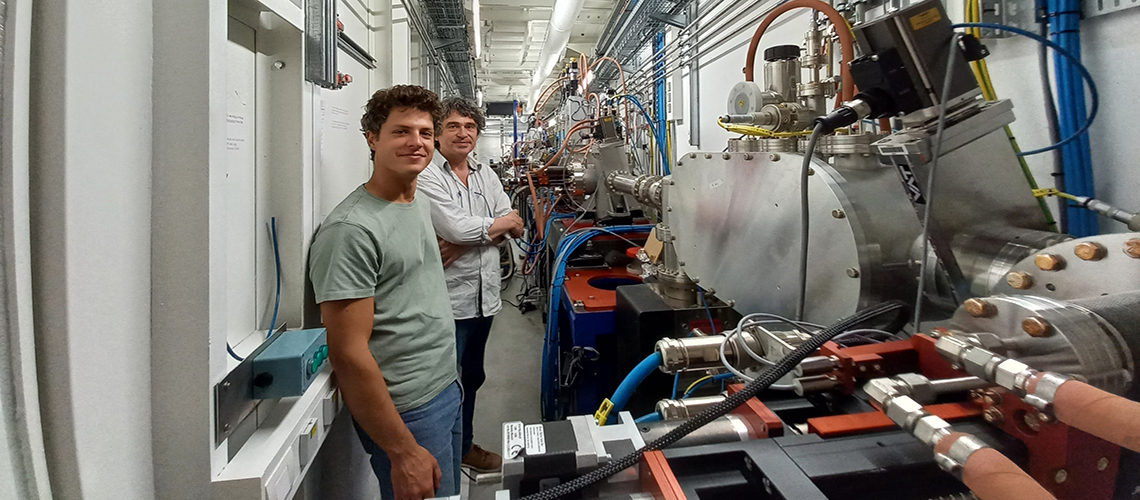

Luigi Manuelli (UNIGE) and Lionel Cavin (MHNG) at the Grenoble synchrotron (ESRF).

© K. Dollman

Coelacanths are fish represented today by only two existing species and which, with a few exceptions, have evolved very slowly over more than 400 million years. The fossils analyzed by the international team were discovered in clay nodules from the Middle Triassic in Lorraine, France, near Saverne. The specimens, about six inches (15 cm) long, are preserved in three dimensions.

Several of them were analyzed at the ESRF synchrotron in Grenoble. This instrument is a particle accelerator, where electrons circulate in a ring with a diameter of 1,050 feet (320 meters) and produce X-rays called "synchrotron light." This light is used to study matter and can produce images of fossils preserved in rock. After hundreds of hours of work to virtually separate the skeletal bones in digital form, 3D virtual models of the fossils were created, which can be easily studied.

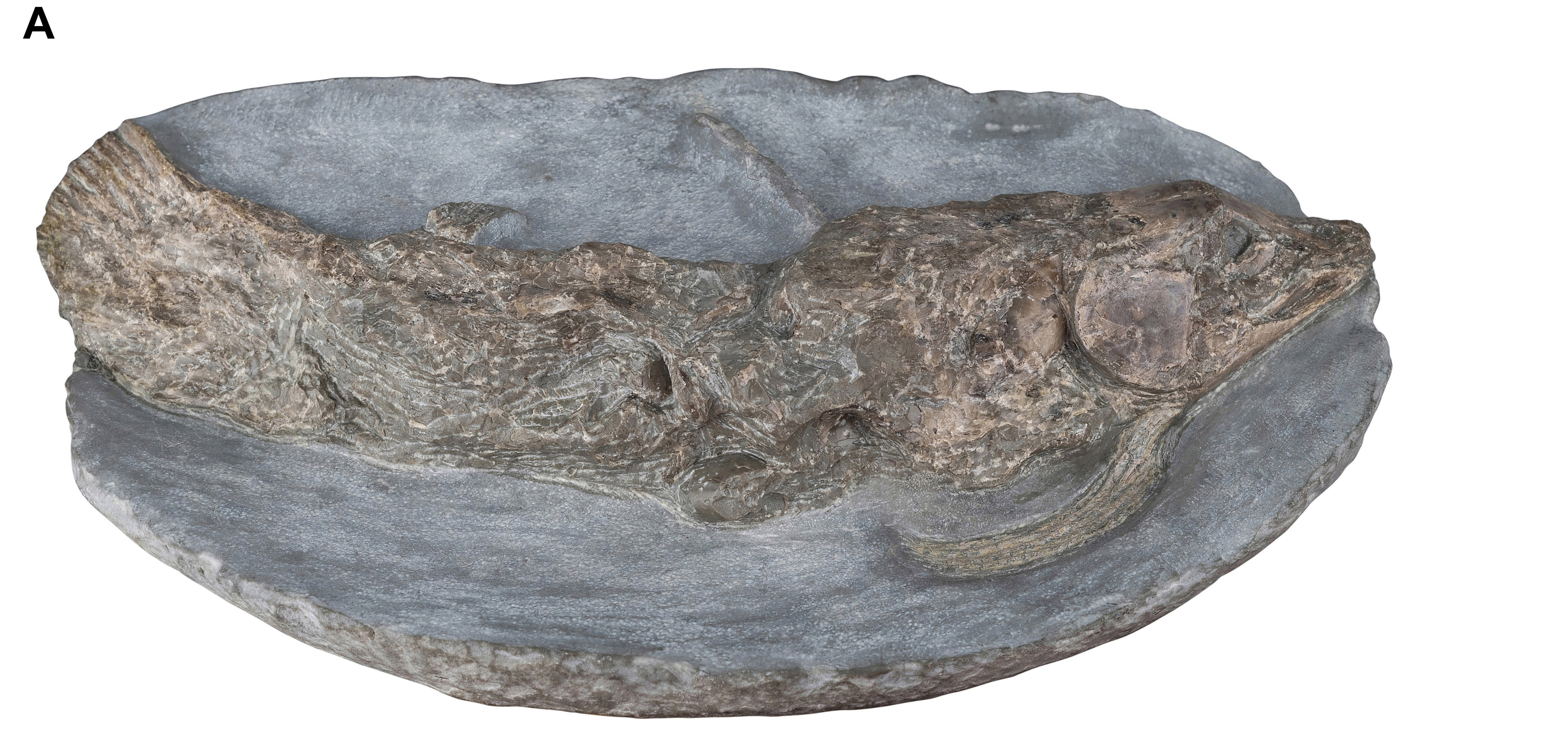

Coelacanth fossil partially exposed from the encasing rock.

© P. Wagneur - MHNG

Luigi Manuelli, then a doctoral student in the Department of Genetics and Evolution at UNIGE and at the Geneva Natural History Museum in the team of paleontologist Lionel Cavin, carried out this work as part of a project supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation. The results obtained allow the reconstruction of the skeletons of these fish with a level of detail never before achieved for this type of fossil. This is a new species named Graulia branchiodonta, after the Graoully, a mythical dragon from Lorraine folklore, and referencing the large teeth these fish have on their gills.

The specimens are juvenile individuals characterized in particular by highly developed sensory canals. It was likely a much more active species than the modern coelacanth, Latimeria, whose behavior is very sluggish. Graulia also had a large gas bladder, which could have served respiratory, auditory, or buoyancy functions. This strange feature is currently being studied by the Geneva team and will undoubtedly unveil surprising insights.

3D rendering of Graulia branchiodonta specimens after the "digital removal" of the rock.

© L. Manuelli - MHNG

The Geneva museum's team continues to study Triassic coelacanths that lived a few million years after the largest mass extinction of the last 500 million years, by describing new fossils discovered in various locations around the world. They are interested not only in their astonishing morphological characteristics but also in their genetics, by comparing the genomes of present-day vertebrates.