These fossils reveal what pterosaurs ate 182 million years ago 🍖

Published by Cédric,

Article author: Cédric DEPOND

Source: Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology

Other Languages: FR, DE, ES, PT

Article author: Cédric DEPOND

Source: Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology

Other Languages: FR, DE, ES, PT

Follow us on Google News (click on ☆)

Credit: Gabriel Ugueto

In the heart of the Posidonia Shale in Germany, fossils reveal well-preserved secrets of these flying giants. What did they really eat?

At this exceptional site, two pterosaur fossils were discovered with their last fossilized meal, a rare find. These specimens, 182 million years old, belong to the genera Dorygnathus and Campylognathoides, each with its own distinctive diet.

The food remnants in their stomachs highlight their varied dietary preferences. While Dorygnathus fed on small fish, Campylognathoides preferred squids, a discovery which complicates our understanding of the Jurassic ecosystem.

The particular conditions of the Posidonia Shale, such as low oxygen levels and deposits of fine mud, enabled this unique preservation. This site is celebrated for its well-preserved fossils, including remains of ichthyosaurs and plesiosaurs, providing valuable clues about marine life from that era.

Analyses conducted by Dr. Samuel Cooper and his team confirm this dietary diversity. Dorygnathus likely caught fish by flying over water, whereas Campylognathoides targeted larger prey like squids.

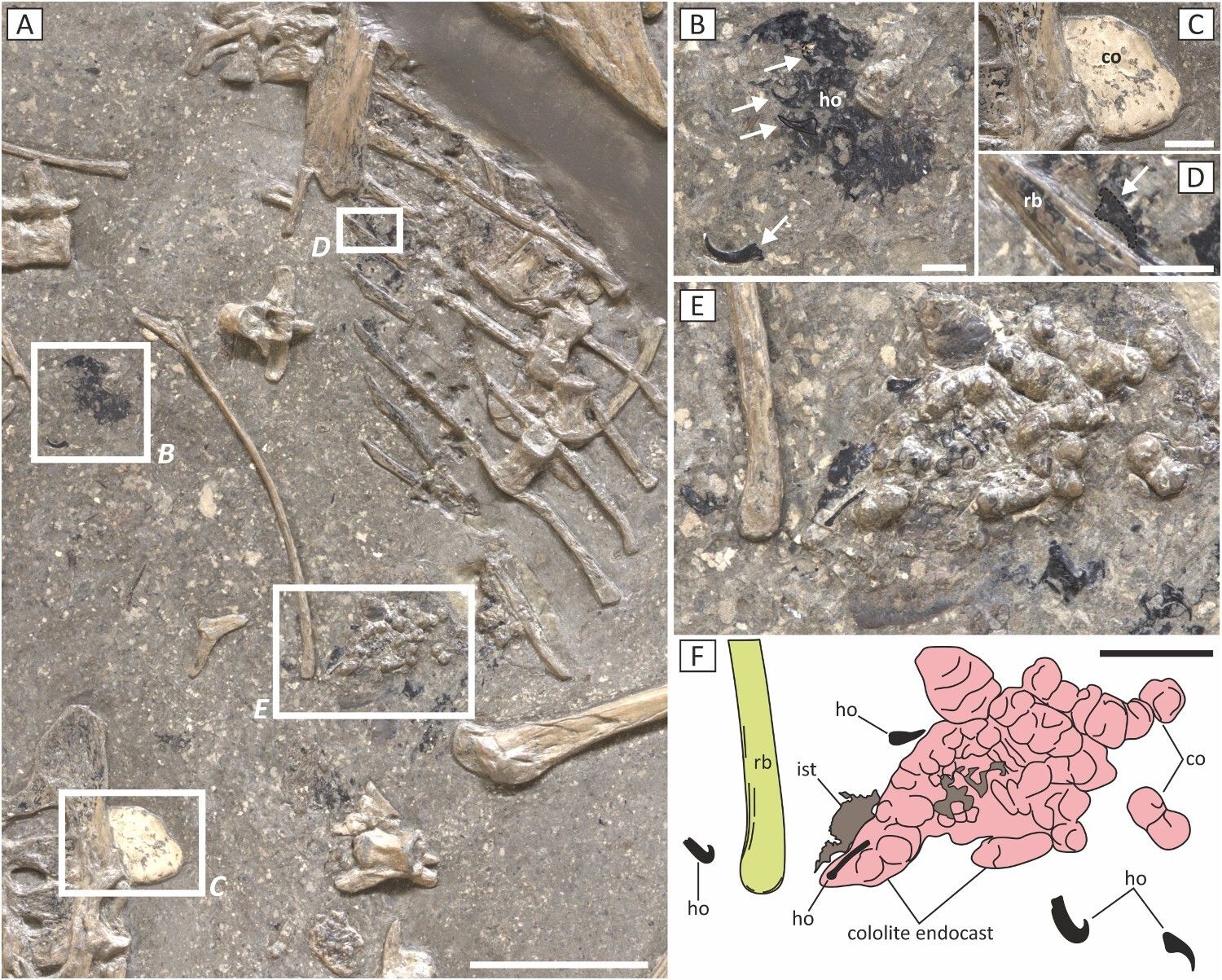

A: General view of the abdominal region of the trunk.

B: Details of the organic mass with indeterminate soft tissues and four isolated hooks of Clarkeiteuthis conocauda.

C: Smoothed cololite nodule (pre-coprolite), potentially associated with the rectal cavity.

D: Belemnoid hook worn by acid (Clarkeiteuthis conocauda) between the abdominal ribs.

E–F: Central abdominal mass of soft tissues and stomach contents with several belemnoid hooks and cololite partially filling the intestinal tract.

Abbreviations: co, cololite; ho, hooks; ist, indeterminate soft tissues; rb, rib. Scales: 2 in (50 mm) (A), 0.4 in (10 mm) (E, F), 0.2 in (5 mm) (B–D).

These distinct diets demonstrate a coexistence without competition. Each species specialized in capturing different prey, showcasing a remarkable evolutionary adaptation.

This fragment of a Jurassic meal is on public display at the Natural History Museum in Stuttgart, offering a direct insight into the lives of pterosaurs 182 million years ago. It's an invitation to explore the well-guarded secrets of these flying reptiles' history.

What is a pterosaur?

Pterosaurs are prehistoric flying reptiles that lived during the age of the dinosaurs, between the Triassic and the end of the Cretaceous period (about 228 to 66 million years ago). Unlike dinosaurs, who dominated the land, pterosaurs evolved in the skies and, depending on the species, had wingspans ranging from a few dozen centimeters to over 32 feet (10 meters).

Equipped with wing membranes attached to the four fingers of their wings, they could glide or perform agile maneuvers to catch their prey. Adapted to aquatic environments, they were primarily piscivorous.

How do stomach fossils form?

The fossilization of stomach contents is a rare process, as soft tissues decompose quickly after the animal's death. For food remnants to fossilize, specific environmental conditions are required. Slowed decay, often due to low oxygen or fine sediment deposits, can allow for exceptional preservation.

In the Posidonia Shale, the low oxygen levels in the seafloor and deposits of fine mud prevented rapid decomposition. These unique conditions account for the preservation of the pterosaur stomach contents, enabling researchers to uncover their last meal.

The Posidonia Shale: an exceptional fossil site

The Posidonia Shale, a 182 million-year-old rock formation, is located in southwestern Germany. This site is famous for its exceptionally preserved fossils, particularly of marine creatures like ichthyosaurs, plesiosaurs, and ammonites, which attest to a rich biodiversity.

The fossils reveal essential information about the anatomy, behavior, and environment of prehistoric species. By analyzing pterosaur stomach fossils, paleontologists can reconstruct key aspects of their diet and ecological interactions. These analyses also help scientists understand how certain species coexisted by exploiting different resources, contributing to our knowledge of ancient ecosystems and the evolution of ecological niches.