Follow us on Google News (click on ☆)

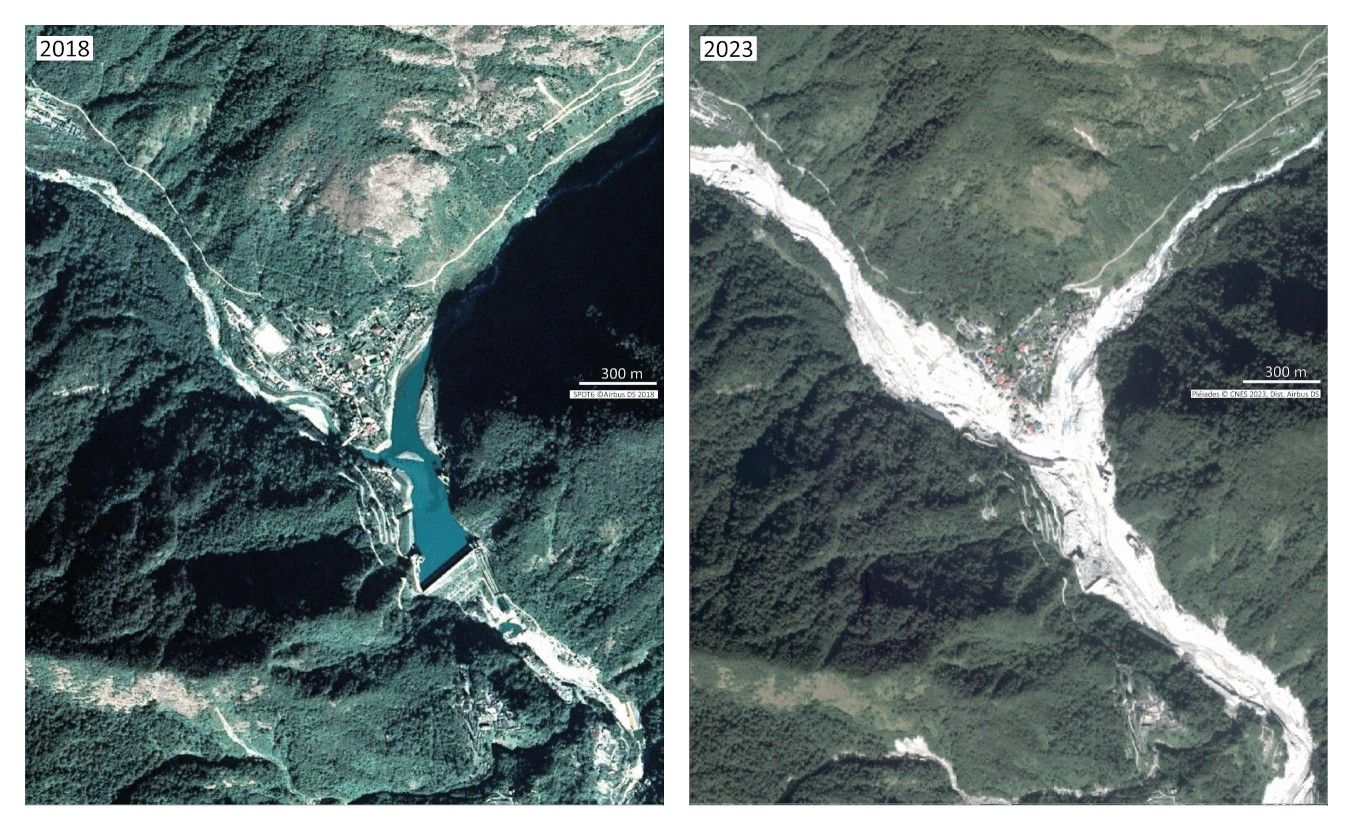

Satellite images before/after of the village of Chungthang, Sikkim, and the Teesta III hydroelectric dam, showing the destruction of the power plant and the damage to the village.

In the end, the flood caused nearly 130 deaths or disappearances and damaged around 26,000 buildings, 31 major bridges, 11.5 miles (18.5 km) of roads, and five hydroelectric dams.

An international multidisciplinary team, including scientists from CNRS Earth & Universe (see box), was formed to investigate the causes, dynamics, and impacts of this devastating flood.

The flood originated at South Lhonak Lake, a large proglacial lake located in a remote region of the Himalayas. On October 3 at 10:12 PM (local time), an entire section of the glacial moraine on the northern shore of the lake collapsed. This mass of sediment and ice, measuring 2,953 feet (900 m) long and 289 feet (88 m) wide, fell into the lake, creating a tsunami approximately 66 feet (20 m) high.

This wave breached the dam holding back the lake, releasing about 50 million cubic meters (1.77 billion cubic feet) of water, equivalent to 20,000 Olympic-sized swimming pools. This series of events can be linked to the retreat of the South Lhonak Glacier and the warming of permafrost in response to rising temperatures in the region.

As it flowed down the Teesta River, the flood carried enormous amounts of rock and soil from the riverbed and banks. In many places, this erosion caused the slopes above the river to collapse. The flood triggered 45 landslides and added approximately 270 million cubic meters (9.54 billion cubic feet) of material to the floodwaters, increasing the flood volume by a factor of 5.

This material played a key role in the flood damage, as many downstream villages were buried under meters of sand and gravel. Nearly half of the buildings damaged by the flood had been built in the last ten years, illustrating how urbanization in at-risk areas can contribute to disasters.

The team was able to quickly obtain high-resolution images of the affected area, taken by the Pléiades satellites (CNES/Airbus DS). These stereoscopic pairs allowed for the creation of highly detailed 3D models of the terrain across much of the flood-affected region.

Pre-flood images were also available, thanks to the Dinamis program, enabling the creation of detailed 3D models before the disaster. The resulting change maps provide a very detailed view of erosion and sediment deposition following a major GLOF event and indicate that, in just a few days, the equivalent of 3.5 inches (9 cm) of erosion occurred in this Himalayan watershed.

Thousands of glacial lakes exist in the Himalayas, and GLOFs are likely to pose an increasing risk as glaciers continue to retreat and permafrost warming intensifies.

Reference:

Ashim Sattar et al.,The Sikkim flood of October 2023: Drivers, causes and impacts of a multihazard cascade.

Science,eads2659.